(Press-News.org)

According to the United Nations, soil salinization affects between 20% and 40% of arable land globally, with human activity and climate change – especially rising sea levels – largely responsible for this process. While the human body needs sodium to function, this is not the case for most plants. In fact, excess salt around plants’ roots gradually blocks their access to water, stunting their growth, poisoning them and hastening their death. Ten million hectares of farmland are destroyed by soil salinization every year, posing a threat to global food security.

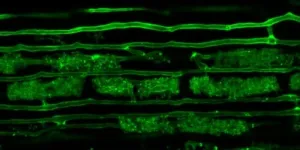

Scientists at EPFL, the University of Lausanne (UNIL) and their Spanish partners observed how ‘Salt Overly Sensitive 1’ (SOS1), a gene identified in 2000, protects the plant cells from salt. The team of biologists and engineers produced unprecedented images using the CryoNanoSIMS (Cryo Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry) ion microprobe. With this cryogenic microscopy instrument – the only one of its kind in the world – they were able to obtain precise images of the location in which a specific nutrient is stored or used within a cell or tissue sample. Their observations show that, under high levels of salt stress, the ion transporter SOS1 no longer removes sodium but rather helps to load it into structures called the vacuoles within the cells. Better understanding this mechanism and working out why some species are more tolerant to sodium than others could, according to the scientists, allow us to develop new strategies to strengthen food security. Their findings have just been published in Nature.

First visual proof

“Our research provides the first visual proof, at the cellular scale, of how plants protect themselves against excess of sodium,” says Priya Ramakrishna, a postdoctoral researcher at EPFL’s Laboratory for Biological Geochemistry (LGB) and the lead author of the paper. “Previous hypotheses of this mechanism were based on indirect evidence. We can now see where sodium is transported to at different levels of salt stress – something we were unable to do at this resolution before.” The joint EPFL and UNIL team carried out observations in unprecedented detail with the recently developed CryoNanoSIMS instrument, that permits obtaining chemical images of biological tissue at a resolution of 100 nanometers, in this case on samples of plant roots that had been snap-frozen in a bath of liquid nitrogen and maintained at very low temperatures under vacuum, to preserve all elements in place in the tissue.

This approach allowed them to map individual plant cells and see where key elements, such as potassium, magnesium, calcium and sodium were stored in plant root tips – the part of the plant known as the “root apical meristem” – that contain the stem cells responsible for the development of the plant root system. The CryoNanoSIMS imaging showed the condition of the root at two different salt stress conditions.

A change of strategy

Under mild salt stress, the cells manage to keep sodium from entering. But the team observed a change of strategy under high salt stress: instead of evacuating the sodium, as previously thought, the SOS1 transporter helps to sequester it into vacuoles that serve to store unwanted products. “But this defense mechanism is energy-intensive, slowing down the plant’s growth, inhibiting its performance and ultimately leading to its death if the salt stress persists,” explains Ramakrishna. The researchers validated their observations by performing the same experiments on mutant samples lacking the SOS1 transporter gene, revealing its inability to transport sodium into the vacuoles, which explains its strongly increased sensitivity to salt. They also ran the tests using root samples taken from rice – the world’s most common crop – and found that, in this case too, the sodium was transported to the vacuole under high salt stress.

Matching location with function

For Ramakrishna, a plant biologist by training, the chemical imaging made possible by the CryoNanoSIMS instrument is a complete game changer. And the instrument could also be used to investigate how plants protect themselves against other threats, such as heavy metal pollution and microbes. “With this kind of truly interdisciplinary collaboration, i.e., blending biology and engineering, we can match location with function and understand mechanisms and processes that have never been observed before,” says corresponding author Anders Meibom, a professor at EPFL’s School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering (ENAC) and UNIL’s Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, in whose laboratory the CryoNanoSIMS instrument was developed.

Niko Geldner, the paper’s co-corresponding author, head of the research team at UNIL's Faculty of Biology and Medicine and leader of the UNIL team, is equally enthusiastic about this collaboration: “Plants are fundamentally dependent on extracting mineral nutrients from the soil, but we were never able to observe their transport and accumulation at sufficient resolution. The CryoNanoSIMS technology finally achieves this and promises to transform our understanding of plant nutrition, beyond the problem of salt.” Professor Christel Genoud, co-author of the paper and Director of the Dubochet Center for Imaging adds: “This technique is opening up an entirely new horizon in the imaging of biological tissue and places our institutions as leaders on this frontier”.

References

Priya Ramakrishna, Francisco M. Gámez-Arjona, Etienne Bellani, Cristina Martin-Olmos, Stéphane Escrig, Damien De Bellis, Anna De Luca, José M Pardo, Francisco J. Quintero, Christelle Genoud, Clara Sánchez-Rodriguez, Niko Geldner and Anders Meibom, “Elemental cryo-imaging reveals SOS1-dependent vacuolar sodium accumulation”, Nature, 15 January 2025.

END

While most known types of DNA damage are fixed by our cells’ in-house DNA repair mechanisms, some forms of DNA damage evade repair and can persist for many years, new research shows. This means that the damage has multiple chances to generate harmful mutations, which can lead to cancer.

Scientists from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their collaborators analysed family trees of hundreds of single cells from several individuals. The team pieced together these family trees from patterns of shared mutations between the cells, indicating common ancestors.

Researchers uncovered unexpected ...

Researchers have discovered a biological mechanism that makes plant roots more welcoming to beneficial soil microbes.

This discovery by John Innes Centre researchers paves the way for more environmentally friendly farming practices, potentially allowing farmers to use less fertiliser.

Production of most major crops relies on nitrate and phosphate fertilisers, but excessive fertiliser use harms the environment.

If we could use mutually beneficial relationships between plant roots and soil microbes to enhance nutrient uptake, ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Nearly 50 years ago, neuroscientists discovered cells within the brain’s hippocampus that store memories of specific locations. These cells also play an important role in storing memories of events, known as episodic memories. While the mechanism of how place cells encode spatial memory has been well-characterized, it has remained a puzzle how they encode episodic memories.

A new model developed by MIT researchers explains how those place cells can be recruited to form episodic memories, even when there’s no spatial component. According to this model, place cells, along with grid cells found in the entorhinal cortex, act as a scaffold ...

Arizona State University and a team of its collaborators have received $11.2 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Energy to begin developing a regional Direct Air Capture (DAC) Hub for removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. The team will prepare to build a multi-site Direct Air Capture Hub located in the Four Corners area of the Southwestern United States. Additionally, the project will receive $11.2 million in matching funds from the project partners.

In May of 2022, the Biden administration announced the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s $3.5 billion DOE program to establish large-scale Direct Air Capture Hubs for removing carbon ...

Isotretinoin, commonly referred to as Accutane, is the only approved medical treatment capable of inducing long-term remission of severe acne. Although highly effective, some individuals experience recurrence of acne after a course of treatment. A new study from researchers at Mass General Brigham examined how often acne recurs after isotretinoin and what factors might put patients at risk of acne coming back. They found that acne recurrence necessitating treatment with an oral medication such as oral antibiotics, spironolactone, or another ...

New proteins not found in nature have now been designed to counteract certain highly poisonous components of snake venom. The deep learning, computational methods for developing these toxin-neutralizing proteins offer hope for creating safer, more cost-effective and more readily available therapeutics than those currently in use.

Each year more than 2 million people suffer snakebites. More than 100,000 of them die, according to the World Health Organization, and 300,000 suffer severe complications and lasting disability ...

Proteins are the foundation of all life we currently know. With their virtually limitless diversity, they can perform a broad variety of biological functions, from delivering oxygen to cells and acting as chemical messengers to defending the body against pathogens. Furthermore, most biochemical reactions are only possible thanks to enzymes, a special type of protein catalysts.

The molecular surface of proteins is the key to their function, such as docking small molecules or other proteins or driving ...

An international team of geneticists, led by those from Trinity College Dublin, has joined forces with archaeologists from Bournemouth University to decipher the structure of British Iron Age society, finding evidence of female political and social empowerment.

The researchers seized upon a rare opportunity to sequence DNA from many members of a single community. They retrieved over 50 ancient genomes from a set of burial grounds in Dorset, southern England, in use before and after the Roman Conquest of AD 43. The results revealed that this community was centred around bonds of female-line descent.

Dr Lara Cassidy, Assistant Professor in Trinity’s Department of Genetics, led ...

Researchers at Nagoya University in Japan have discovered sophisticated behavioral strategies that enable parasitic crickets to survive within ant colonies. Led by Ryoya Tanaka, the team documented how these insects successfully navigate life among potentially lethal hosts through precise evasion tactics. Their findings, published in Communications Biology, reveal remarkable adaptations that allow these cricket species to thrive in a hostile environment.

Animals that live in ant colonies, known as “ant guests”, exploit their hosts’ resources. However, this ...

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a reliable and reproducible way to fabricate tapered polymer optical fibers that can be used to deliver light to the brain. These fibers could be used in animal studies to help scientists better understand treatments and interventions for various neurological conditions.

The tapered fibers are optimized for neuroscience research techniques, such as optogenetic experiments and fiber photometry, which rely on the interaction between genetically modified neurons and visible light delivered to and/or collected from the brain.

“Unlike standard optical fibers, which are cylindrical, the tapered fibers we developed have a conical shape, which ...