(Press-News.org) Athens, Ga. – It's a common assumption that animal migration, like human travel across the globe, can transport pathogens long distances, in some cases increasing disease risks to humans. West Nile Virus, for example, spread rapidly along the East coast of the U.S., most likely due to the movements of migratory birds. But in a paper just published in the journal Science, researchers in the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology report that in some cases, animal migrations could actually help reduce the spread and prevalence of disease and may even promote the evolution of less-virulent disease strains.

Every year, billions of animals migrate, some taking months to travel thousands of miles across the globe. Along the way, they can encounter a broad range of pathogens while using different habitats and resources. Stopover points, where animals rest and refuel, are often shared by multiple species in large aggregations, allowing diseases to spread among them.

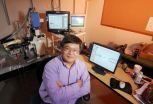

But, according to Odum School associate professor Sonia Altizer and her co-authors, Odum School postdoctoral associates Rebecca Bartel and Barbara Han, migration can also help limit the spread of some pathogens.

Some kinds of parasites have transmission stages that can build up in the environment where host animals live, and migration allows the hosts to periodically escape these parasite-laden habitats. While hosts are gone, parasite numbers become greatly reduced so that the migrating animals find a largely disease-free habitat when they return. Long migratory journeys can also weed infected animals from the population: imagine running a marathon with the flu. This not only prevents those individuals from spreading disease to others, it also helps to eliminate some of the most virulent strains of pathogens.

"By placing disease in an ecological context," said Odum School dean John Gittleman, "you not only see counterintuitive patterns but also understand advantages to disease transmission. This is a classic example of disease ecology at its best."

Altizer's long-term research on monarch butterflies and a protozoan parasite that infects them provides an excellent demonstration of migration's effects on the spread of infectious disease. Monarchs in eastern North America migrate long distances, from as far north as Canada, to central Mexico, where they spend the winter. Monarchs in other parts of the world migrate shorter distances. In locations with mild year-round climates, such as southern Florida and Hawaii, monarchs do not migrate at all. Work by Altizer and others in her lab showed that parasite prevalence is lowest in the eastern North American population, which migrates the farthest distance, and highest in non-migratory populations. This could be because infected monarchs do not migrate successfully, as suggested by tethered-flight experiments with captive butterflies, or because parasites build up in habitats where monarchs breed year-round. Other work showed that parasites isolated from monarchs that flew the longest were less virulent than those found in monarchs that flew shorter distances or didn't migrate at all, suggesting that monarchs with highly virulent parasites didn't survive the longest migrations.

"Taken together, these findings tell us that migration is important for keeping monarch populations healthy—a result that could apply to many other migratory animal species," said Altizer.

But for monarchs, and many other species, migration is now considered an endangered phenomenon. Deforestation, urbanization and the spread of agriculture have eliminated many stopover sites, and artificial barriers such as dams and fences have blocked migration routes for other species. These changes can artificially elevate animal densities and facilitate contact between wildlife, livestock and humans, increasing the risk that pathogens will spread across species. As co-author Han noted, "A lot of migratory species are unfairly blamed for spreading infections to humans, but there are just as many examples suggesting the opposite—that humans are responsible for creating conditions that increase disease in migratory species."

And as the climate warms, species like the monarch may no longer need to undertake the arduous migratory journey to their wintering grounds. With food resources available year-round, some species may shorten or give up their migrations altogether—prolonging their exposure to parasites in the environment, raising the rates of infection and favoring the evolution of more virulent disease strains. "Migration is a strategy that has evolved over millions of years in response to selection pressures driven by resources, predators and lethal parasitic infections—any changes to this strategy could translate to changes in disease dynamics," said Han.

"There is an urgent need for more study of pathogen dynamics in migratory species and how human activities affect those dynamics," Altizer said. The paper concludes with an outline of challenges and questions for future research. "We need to learn more in order to make decisions about the conservation and management of wildlife and to predict and mitigate the effects of future outbreaks of infectious diseases."

INFORMATION: END

In a new paper published Jan. 21 in the journal Science, a team of researchers led by Microbiology and Immunology professor Blossom Damania, PhD, has shown for the first time that the Kaposi sarcoma virus has a decoy protein that impedes a key molecule involved in the human immune response.

The work was performed in collaboration with W.R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor, Jenny Ting, PhD. First author, Sean Gregory, MS, a graduate student in UNC's Department of Microbiology and Immunology played a critical role in this work.

The virus-produced protein, called ...

VIDEO:

This video shows the micropipette adhesion frequency assay used to study the mechanical interactions between a T cell and an antigen presented on a red blood cell.

Click here for more information.

Researchers have for the first time mapped the complex choreography used by the immune system's T cells to recognize pathogens while avoiding attacks on the body's own cells.

The researchers found that T cell receptors – molecules located on the surface of the T cell ...

The discovery of an ancient fossil, nicknamed 'Mrs T', has allowed scientists for the first time to sex pterodactyls – flying reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs between 220-65 million years ago.

Pterodactyls featured prominently in Spielberg's Jurassic Park III and are a classic feature of many dinosaur movies where they are often depicted as giant flying reptiles with a crest.

The discovery of a flying reptile fossilised together with an egg in Jurassic rocks (about 160 million years old) in China provides the first direct evidence for gender in these extinct ...

In 2008, an international team of scientists studying an exotic new superconductor based on the element ytterbium reported that it displays unusual properties that could change how scientists understand and create materials for superconductors and the electronics used in computing and data storage.

But a key characteristic that explains the material's unusual properties remained tantalizingly out of reach in spite of the scientists' rigorous battery of experiments and exacting measurements. So members of that team from the University of Tokyo reached out to theoretical ...

Scientists from the University of Leeds have made a fundamental step in the search for therapies for amyloid-related diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and diabetes mellitus. By pin-pointing the reaction that kick-starts the formation of amyloid fibres, scientists can now seek to further understand how these fibrils develop and cause disease.

Amyloid fibres, which are implicated in a wide range of diseases, form when proteins misfold and stick together in long, rope-like structures. Until now the nature of the first misfold, which then causes a chain reaction of ...

The anti-diuretic hormone "vasopressin" is released from the brain, and known to work in the kidney, suppressing the diuresis. Here, the Japanese research team led by Professor Yasunobu OKADA, Director-General of National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), and Ms. Kaori SATO, a graduate student of The Graduate University for Advanced Studies, clarified the novel function of "vasopressin" that works in the brain, as well as in the kidney via the same type of the vasopressin receptor, to maintain the size of the vasopressin neurons. It might be a useful result for ...

Humans use their senses to help keep track of short intervals of time according to new research, which suggests that our perception of time is not maintained by an internal body clock alone.

Scientists from UCL (University College London) set out to answer the question "Where does our sense of time come from?" Their results show that it comes partly from observing how much the world changes, as we have learnt to expect our sensory inputs to change at a particular 'average' rate. Comparing the change we see to this average value helps us judge how much time has passed, ...

For centuries, some of the greatest names in math have tried to make sense of partition numbers, the basis for adding and counting. Many mathematicians added major pieces to the puzzle, but all of them fell short of a full theory to explain partitions. Instead, their work raised more questions about this fundamental area of math.

On Friday, Emory mathematician Ken Ono will unveil new theories that answer these famous old questions.

Ono and his research team have discovered that partition numbers behave like fractals. They have unlocked the divisibility properties of ...

SPOKANE, Wash.— Washington State University sleep researchers have determined that the air traffic controller in the crash of a Lexington, Ky., commuter flight was substantially fatigued when he failed to detect that the plane was on the wrong runway and cleared it for takeoff.

Writing in the journal Accident Analysis and Prevention, the researchers come short of saying his fatigue caused the accident. But they say their findings suggest that mathematical models predicting fatigue could lead to schedules that reduce the risk of accidents by taking advantage of workers' ...

The ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law acknowledges the benefits that IMAR may bring to those choosing this approach and concludes that certain forms of IMAR are morally acceptable under certain conditions. The group advises to evaluate each request for IMAR individually, based on four ethical principles in health care: the respect for autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence and justice.

The Task Force explains that the right for individual autonomy is elementary: any individual should have the principle of choice with whom to reproduce. It is understandable that couples ...