(Press-News.org) New University of Virginia School of Medicine research revealing the fingerprints of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome within blood samples could open the door to simple tests to identify babies at risk.

The findings also represent an important step forward in unraveling the causes of SIDS, an unexplained condition that is the No. 1 killer of babies between amonth and a year old.

The UVA researchers analyzed blood serum samples collected from infants who died from SIDS and were able to identify specific biological indicators that were linked to – and potential causes of – the babies’ deaths.

Tests to identify such signs in infants could ultimately help save lives, the researchers say.

“Our study is the largest study to date that has attempted to detect how these small molecules in the blood may serve as biomarkers for SIDS,” said researcher Keith L. Keene, PhD, founding director of UVA’s Center for Health Equity and Precision Public Health and now at East Carolina University. “Our findings support a role for multiple key biological pathways and provide insight into how those biological processes may contribute to increased risk or serve to diagnose SIDS.”

Understanding SIDS

The new research speaks to the potential of “metabolomics,” the analysis of substances called metabolites produced by cells, for better understanding and treating complex diseases, the scientists say.

In their SIDS work, the UVA researchers analyzed blood serum samples collected from 300 babies included in the Chicago Infant Mortality Study and the National Institutes of Health’s NeuroBioBank. The researchers assessed levels of 828 different metabolites in key biological processes such as nerve cell communication, stress response and hormone regulation – processes that could be contributors to SIDS.

After adjusting for factors that could bias the results, such as the infants’ age, sex, and race and ethnicity, the researchers identified 35 predictors of SIDS. These “biomarkers” included ornithine, a substance critical to the body’s ability to dispose of ammonia in urine. The amino acid has already been identified as a potential contributor to SIDS.

Another predictor was a lipid metabolite that is critical for brain and lung health. This metabolite is already considered a potential indicator for the development of fetal heart defects during the first trimester of pregnancy.

“We found differences in specific fats, called sphingomyelins, which are critical for brain and lung development,” said researcher Chad Aldridge, DPT, MS-CR, of the School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology. “Differences in these fats may disrupt these critical processes, placing some infants at risk for SIDS.”

The UVA scientists caution that further research is needed to determine if the metabolites are contributing to SIDS. But the findings lay an important foundation, they say, for unraveling the mysteries of SIDS and developing blood tests that could potentially save new parents from heartbreak.

“The results of this study are very exciting – we are getting closer to explaining the pathways leading to a SIDS death,” said researcher Fern R. Hauck, MD, MS, a family medicine physician at UVA Health, director of the Chicago Infant Mortality Study and aleading expert on SIDS. “Our hope is that this research lays the groundwork to help identify –through simple blood tests – infants who are at higher risk for SIDS and to save these precious lives.”

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal eBioMedicine. The research team consisted of Aldridge, Keene, Cornelius A. Normeshie, Josyf C. Mychaleckyj and Hauck. A list of the authors’ disclosures is included in the paper.

UVA’s research was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant5R01HD101518-04.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

SIDS discovery could ID babies at risk of sudden death

2025-01-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ozone exposure linked to hypoxia and arterial stiffness

2025-01-22

Ozone (O3) exposure may reduce the availability of oxygen in the body, resulting in arterial stiffening due to the body’s natural response to create more red blood cells and hemoglobin, according to a study published today in JACC, the flagship journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Researchers found that even brief exposure to elevated ozone levels reduced blood oxygen saturation, triggered hypoxia-related biomarkers, and increased arterial stiffness, highlighting the novel connection between ozone exposure and arterial stiffness, demonstrated through comprehensive biomarker analysis in a high-altitude ...

Princeton Chemistry develops copper-detection tool to discover possible chelation target for lung cancer

2025-01-22

The Chang Lab at Princeton Chemistry continues in its mission to elucidate the role of metal nutrients in human biology: last year, iron; this year, copper. The lab’s first paper of 2025 showcases its development of a revelatory sensing probe for the detection of copper in human cells and then wields it to uncover how copper may be regulating cell growth in lung cancer.

Researchers also offer a possible treatment modality in which copper chelation shows promising results in certain lung cancers where cells have two related phenomena: a heightened transcription factor responding to oxidative stress and a diminished level of bioavailable copper.

Their collaborative paper, A histochemical ...

Drug candidate eliminates breast cancer tumors in mice in a single dose

2025-01-22

Despite significant therapeutic advances, breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related death in women. Treatment typically involves surgery and follow-up hormone therapy, but late effects of these treatments include osteoporosis, sexual dysfunction and blood clots. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have created a novel treatment that eliminated small breast tumors and significantly shrank large tumors in mice in a single dose, without problematic side effects.

Most breast cancers are ...

WSU study shows travelers are dreaming forward, not looking back

2025-01-22

PULLMAN, Wash. – When it comes to getting people to want to go places, the future is ever more lovely than the past, according to a new Washington State University-led study in the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research.

Led by Ruiying Cai, an assistant professor in the Carson College of Business, the study found that forestalgia-focused destination ads—those that emphasize an idealized future—are more effective at enticing travelers to click the purchase button for a vacation than ads based on fond recollections. The research also revealed that forestalgia advertising is particularly effective for getting people to book near-term trips, as imagining ...

Black immigrants attract white residents to neighborhoods

2025-01-22

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Black immigrants moving into a neighborhood can help shift the overall racial and ethnic character of the area, a new study suggests.

A researcher from The Ohio State University found that when Black immigrants move into a majority native-Black neighborhood, there is an increase in the white population moving in while native Black residents move out.

“Blackness can’t be treated as a monolith within the United States today, where there is a growing Black immigrant population,” said Nima Dahir, author of the study and assistant professor of sociology at Ohio State.

“There is a lot of complexity ...

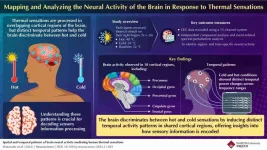

Hot or cold? How the brain deciphers thermal sensations

2025-01-22

When we touch something hot or cold, the temperature is consciously sensed. Previous studies have shown that the cortex, the outermost layer of the brain, is responsible for thermal sensations. However, how the cortex determines whether something is hot or cold is not well understood. Thermal sensitivity is often subjective and individualistic; what is a comfortable temperature for someone might be too hot or too cold for someone else.

In a new study, Professor Kei Nagashima from the Body Temperature and Fluid Laboratory, Faculty of Human Sciences, ...

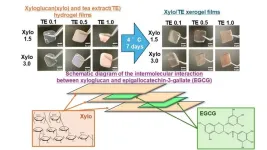

Green tea-based adhesive films show promise as a novel treatment for oral mucositis

2025-01-22

Green tea shines as a natural powerhouse of antioxidants, with catechins leading the charge among its polyphenols, which protect cells from oxidative stress. These powerful compounds neutralize harmful free radicals generated during cancer treatment. The anti-inflammatory properties of green tea can alleviate oral mucositis, a painful inflammation of the mouth lining often caused by chemotherapy and radiation.

Building on these benefits, researchers at the Tokyo University of Science (TUS), Japan, have explored the potential of tea catechins in developing ...

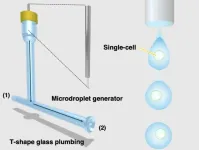

Single-cell elemental analysis using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

2025-01-22

Trace metals are crucial for the growth of all living organisms. Understanding the role of these trace metals on the metabolism is essential for maintaining a stable state of the organism. Additionally, human beings are also facing constant exposure to various harmful heavy metals due to various types of pollution. Collectively, these aspects have led to research and development in the field of analytical techniques that can help in identifying the level of these trace metals in our cells.

Inductively coupled ...

BioChatter: making large language models accessible for biomedical research

2025-01-22

Large language models (LLMs) have transformed how many of us work, from supporting content creation and coding to improving search engines. However, the lack of transparency, reproducibility, and customisation of LLMs remains a challenge that restricts their widespread use in biomedical research.

For biomedical researchers, optimising LLMs for a specific research question can be daunting, because it requires programming skills and machine learning expertise. Such barriers have reduced the adoption of LLMs for many research tasks, including data extraction and analysis.

A new publication in Nature Biotechnology introduces BioChatter to help overcome ...

Grass surfaces drastically reduce drone noise making the way for soundless city skies

2025-01-22

The findings, published today in Scientific Reports, show, for the first time, how porous ground treatments can mitigate noise and optimise propellor performance.

Lead author Dr Hasan Kamliya Jawahar from the University of Bristol’s aeroacoustic group managed by Professor Mahdi Azarpeyvand was able to demonstrate that porous ground treatments, can significantly reduce noise by up to 30 dB in low-mid frequencies and enhance thrust and power coefficients compared to solid ground surfaces. This suggests that treating roofs of building, ...