(Press-News.org) How Hungry Fat Cells Could Someday Starve Cancer to Death

Scientists transformed energy-storing white fat cells into calorie-burning ‘beige’ fat. Once implanted, they outcompeted tumors for resources, beating back five different types of cancer in lab experiments.

Liposuction and plastic surgery aren’t often mentioned in the same breath as cancer.

But they are the inspiration for a new approach to treating cancer that uses engineered fat cells to deprive tumors of nutrition.

Researchers at UC San Francisco used the gene editing technology CRISPR to turn ordinary white fat cells into “beige” fat cells, which voraciously consume calories to make heat.

Then, they implanted them near tumors the way plastic surgeons inject fat from one part of the body to plump up another. The fat cells scarfed up all the nutrients, starving most of the tumor cells to death. The approach even worked when the fat cells were implanted in mice far from the sites of their tumors.

Relying on common procedures could hasten the approach’s arrival as a new form of cellular therapy.

“We already routinely remove fat cells with liposuction and put them back via plastic surgery,” said Nadav Ahituv, PhD, director of the UCSF Institute for Human Genetics and professor in the Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences. He is the senior author of the paper, which appears Feb. 4 in Nature Biotechnology.

“These fat cells can be easily manipulated in the lab and safely placed back into the body, making them an attractive platform for cellular therapy, including for cancer.”

Beige fat cells outcompete cancer cells for nutrients

Ahituv and his post-doc at the time, Hai Nguyen, PhD, were aware of studies that showed exposure to cold could suppress cancer in mice.

One remarkable experiment even showed it could help a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Scientists concluded that the cancer cells were starving because the cold was activating brown fat cells, which use nutrients to produce heat.

But cold therapy isn’t a viable option for cancer patients with fragile health.

So, Ahituv and Nguyen turned to the idea of using beige fat, wagering that they could engineer it to burn enough calories, even in the absence of cold, to deprive tumors of the fuel they needed to grow.

Nguyen, who is the first author of the paper, used CRISPR to activate genes that are dormant in white fat cells but are active in brown fat cells, in the hopes of finding the ones that would transform the white fat cells into the hungriest of beige fat cells.

A gene called UCP1 rose to the top.

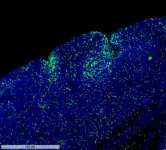

Then, Nguyen grew UCP1 beige fat cells and cancer cells in a “trans-well” petri dish. The cancer cells were on the bottom and the fat cells were above them in separate compartments that kept the cells apart but forced them to share nutrients.

The results were shocking.

“In our very first trans-well experiment, very few cancer cells survived. We thought we had messed something up – we were sure it was a mistake,” Ahituv recalled. “So, we repeated it multiple times, and we kept seeing the same effect.”

The beige fat cells held sway over two different types of breast cancer cells, as well as colon, pancreatic and prostate cancer cells.

But the researchers still didn’t know if the implanted beige fat cells would work in a more realistic context.

Fat cell therapy proves its effectiveness across many cancers in the lab

So, the scientists turned to fat organoids, which are coherent clumps of cells grown in a dish, to see if they could beat tumor cells when they were implanted next to tumors in mice.

The approach worked against breast cancer, as well as pancreatic and prostate cancer cells. The cancer cells starved as the fat cells gobbled up all the available nutrients.

The implanted beige fat cells were so powerful that they suppressed pancreatic and breast tumors in mice that were genetically predisposed to develop cancer. It even worked when the beige fat cells were implanted far away from the breast cancer cells.

To see how they would work in human tissue, Ahituv and Nguyen teamed up with Jennifer Rosenbluth, MD, PhD, a breast cancer specialist at UCSF. Rosenbluth had amassed a library of breast cancer mastectomies containing both fat cells and cancer cells.

“Because the breast has a lot of fat, we could get fat from the same patient, modify the fat, and grow it in a single trans-well experiment with that patient’s own breast cancer cells,” Ahituv said.

These same-patient beige fat cells outcompeted breast cancer cells in petri dishes – and when they were implanted together in mouse models.

Knowing that cancers have preferred diets, the researchers engineered fat just to eat certain nutrients. Certain forms of pancreatic cancer, for example, rely on uridine when glucose is scarce.

So, they programmed the fat to eat just uridine, and they easily outcompeted these pancreatic cancer cells. This suggests that fat could be adapted to any cancer’s dietary preferences.

A new approach to living cell therapy

Fat cells have many advantages when it comes to living cell therapies, according to Ahituv.

Fat cells are easy to obtain from patients. They grow well in the laboratory and can be engineered to express different genes and take on different biological roles. And they behave well once they are put back into the body, not straying from the location where they’re implanted and playing nice with the immune system.

It’s a record borne out by decades of progress in plastic surgery.

“With fat cells, there’s less interaction with the environment, so there's very little worry of the cells leaking out into the body, where they might cause problems,” Ahituv said.

Fat cells can also be programmed to emit signals or carry out more complicated tasks.

And their ability to defeat cancer even when they are not right next to tumors could prove invaluable for treating hard-to-reach cancers like glioblastoma, which affects the brain, as well as many other diseases.

“We think these cells could also be designed to sense glucose in the bloodstream and release insulin, for diabetes, or suck up iron in diseases where there’s excessive iron, like hemochromatosis,” Ahituv said. “The sky’s the limit for these fat cells.”

Authors: In addition to Ahituv, Nguyen, and Rosenbluth, other UCSF authors include Kelly An, Yusuke Ito, Bhushan N. Kharbikar, PhD, Rory Sheng, Breanna Paredes, MS, Elizabeth Murray, Kimberly Pham, Michael Bruck, Xujia Zhou, MS, PhD, Cassidy Biellak, Aki Ushiki, PhD, Mai Nobuhara, MS, Daniel A. Bernards, PhD, Mark Jesus M. Magbanua, PhD, Laura A. Huppert, MD, Heinz Hammerlindl, PhD, Laura Esserman, MD, MBA, Tejal A. Desai, PhD, and Sook Wah Yee, MPharm. For all authors see the paper.

Funding: The work was funded in part by the UCSF Sandler Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, the UCSF Living Therapeutics Initiative, the National Institutes of Health (1R01DK124769, 1R01CA283826) and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Ahituv is a cofounder and on the scientific advisory board of Regel Therapeutics.

Disclosures: Ahituv receives funding from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Incorporate. Ahituv has filed a patent application covering embodiments and concepts disclosed in the manuscript. For all funding and disclosures see the paper.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

How hungry fat cells could someday starve cancer to death

2025-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Breakthrough in childhood brain cancer research could heal treatment-resistant tumors, keep them in remission

2025-02-04

Brain cancer is the second-leading cause of death in children in the developed world. For the children who survive, standard treatments have long-term impacts on their development and quality of life, particularly in small children and infants.

Research out of Emory University and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Queensland, Australia, has shown that a potential new targeted therapy for childhood brain cancer is effective in infiltrating and killing tumor cells in preclinical models tested in mice.

In ...

Research discovery halts childhood brain tumor before it forms

2025-02-04

Scientists at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) have discovered a way to stop tumour growth before it starts for a subtype of medulloblastoma, the most common childhood malignant brain cancer.

Brain cancer presents a unique set of challenges for researchers – by the time a person experiences symptoms, the tumours are often so complex that the fundamental mechanisms driving the tumour growth are no longer easy to identify. A research team led by Dr. Peter Dirks is working to combat ...

Scientists want to throw a wrench in the gears of cancer’s growth

2025-02-04

Preventing the cell’s protein factories from making the notorious cancer-causing protein MYC could stop out-of-control tumors.

For decades, scientists have tried to stop cancer by disabling the mutated proteins that are found in tumors. But many cancers manage to overcome this and continue growing.

Now, UCSF scientists think they can throw a wrench into the fabrication of a key growth-related protein, MYC, that escalates wildly in 70% of all cancers. Unlike some other targets of cancer therapies, MYC can be dangerous simply due to its abundance.

In a paper that appears Feb. 4 in Nature Cell Biology, researchers at UC San Francisco ...

WSU researcher pioneers new study model with clues to anti-aging

2025-02-04

SPOKANE, Wash. — Washington State University scientists have created genetically-engineered mice that could help accelerate anti-aging research.

Globally, scientists are working to unlock the secrets of extending human lifespan at the cellular level, where aging occurs gradually due to the shortening of telomeres–the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that function like shoelace tips to prevent unraveling. As telomeres shorten over time, cells lose their ability to divide for healthy ...

EU awards €5 grant to 18 international researchers in critical raw materials, the “21st century's gold”

2025-02-04

The new EU-funded consortium “ForMovFluid” will study how fluids transformed the materials inside the Earth's crust. Thanks to the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Doctoral Networks programme, ForMovFluid will fund the doctoral studies of 18 researchers, and train them to become elite experts in the field of geoscience.

Moreover, this project will allow us to understand the origin of the so-called critical raw materials, of vital importance for the energy transition. Over a period of four years, ForMovFluid “Marie Curie” researchers ...

FRONTIERS launches dedicated call for early-career science journalists

2025-02-04

FRONTIERS announces a new call for applications for its Science Journalism in Residency Programme, funded by the European Research Council (ERC). This

third call is exclusively aimed at early-career journalists and will remain open until May 6, 2025, at 17h00 CEST.

Science journalists with up to five years of experience are invited to apply for a residency at a research institution of their choice, in an EU Member State or a

country associated with the EU’s Horizon Europe Programme. The residencies, lasting between three to five months, should focus on frontier science topics, in

collaboration with scientists.

The ...

Why do plants transport energy so efficiently and quickly?

2025-02-04

The efficient conversion of solar energy into storable forms of chemical energy is the dream of many engineers. Nature found a perfect solution to this problem billions of years ago. The new study shows that quantum mechanics is not just for physicists but also plays a key role in biology.

Photosynthetic organisms such as green plants use quantum mechanical processes to harness the energy of the sun, as Prof. Jürgen Hauer explains: “When light is absorbed in a leaf, for example, the electronic excitation energy is distributed over several states ...

AI boosts employee work experiences

2025-02-04

A new paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, published by Oxford University Press, shows customer service workers using artificial intelligence assistance become more productive and work faster. The effects vary significantly, however. Less experienced and lower-skilled employees improve both the speed and quality of their work, while the most experienced and highest-skilled workers see small gains in speed and small declines in quality. The researchers also found that AI assistance can help worker learning and improve English fluency, particularly for international workers.

Computers and software have transformed the economy with their ability to perform certain tasks with far ...

Neurogenetics leader decodes trauma's imprint on the brain through groundbreaking PTSD research

2025-02-04

BELMONT, Massachusetts, USA, 4 February 2025 - In a comprehensive Genomic Press Interview, Dr. Kerry Ressler, Chief Scientific Officer at McLean Hospital and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, unveils groundbreaking advances in understanding the neurobiological basis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related anxiety conditions.

Dr. Ressler's research bridges the gap between molecular neuroscience and clinical psychiatry, focusing on how the amygdala processes fear and trauma at cellular and genomic levels. "Most proximally, I hope that our work may lead to novel approaches to fear- and trauma-related disorders, perhaps even to prevent ...

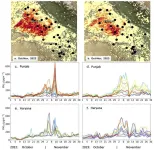

High PM2.5 levels in Delhi-NCR largely independent of Punjab-Haryana crop fires

2025-02-04

International collaborative research led by Aakash Project* researchers at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) show an unequivocal contribution of crop residue burning (CRB) to air pollution in the rural/semi-urban regions of Punjab and Haryana, and a relatively lower contribution than previously thought to the Delhi national capital region (NCR). We have installed 30 units of compact and useful PM2.5** in situ instrument with gas sensors (CUPI-Gs) and have continuously recorded air pollutants in 2022 and 2023. New analytical methods have been developed to assess ...