(Press-News.org) Key points:

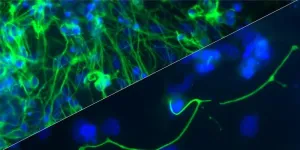

Researchers from the Voigt lab have extended our understanding of how developmental genes are held in a poised state to allow timely expression once they receive the correct ‘go’ signals.

The next layer of regulation has been uncovered by the identification of proteins that interact with the epigenetic marks that poise developmental genes ready for expression.

The research provides insight into the mechanisms through which the phenomenon of bivalency – where both activating and repressive marks are laid down at the same site on the genome – acts to ready developmental genes for activation.

Importantly, the team identified specific interactor proteins that only recognise the bivalent state. Loss of one of these, KAT6B, blocks neuronal differentiation in embryonic stem cells.

This research advances our understanding of the mechanisms that control developmental gene expression. Knowing more about these mechanisms contributes to our ability to maintain the health of cells in ageing and to the development of regenerative technologies such as cell and tissue regeneration and cellular reprogramming.

As well as being essential in the precise packaging of DNA into the space of the nucleus, histone proteins are also the site of modifications, chemical additions referred to as epigenetic marks, that control whether a gene is silenced or expressed. A specialised version of this control is at sites where both activating and repressive marks are laid down, called bivalency. Research from the Voigt lab at the Babraham Institute has investigated the mechanism by which bivalency functions to poise genes for expression during cell differentiation. These findings provide insight into the intricate cellular processes that control development, how cell types are specified from stem cells, and how cell identity is established. Deciphering these mechanisms is not only key to understand fundamental biology but will also ultimately pave the way for the development of regenerative medicine approaches.

The combination of active and repressive marks is thought to hold the gene in a poised state in undifferentiated cells, ready for either full activation or full and permanent repression depending on differentiation cues.

Now the team’s research has shown in part how this balance is achieved and identified the protein interactors that read the bivalent state and influence gene expression.

Dr Devisree Valsakumar, a postdoctoral researcher in the Voigt lab, explained: “Bivalent marks are the gatekeeper of the poised status, which we can compare to the ‘Set’ command of ‘Ready, Set, Go!’. As the later findings of our research showed, this regulation, which holds genes in a ‘ready to go’ state, is critical for the proper specialism of cell types as cells differentiate from stem cells.”

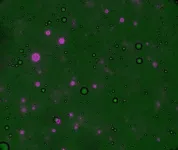

Key to identifying the readers of bivalency was the team’s ability to create specifically modified histones and nucleosomes (where DNA is wound around histone proteins in a ‘beads on a string’ structure). Through painstakingly recreating the DNA and histone protein complexes to allow tailored protein interaction assays, the team have shown that at bivalent locations, proteins were recruited to the repressive mark (H3K27me3) and not to the activating mark (H3K4me3).

Importantly, they discovered that the bivalent combination of activating and repressive marks allows the binding of specific proteins that are not recruited by the repressive (H3K27me3) or activating (H3K4me3) marks individually.

One of these proteins is the histone acetyltransferase complex KAT6B (MORF), identifying this for the first time as a reader of bivalent nucleosomes and regulator of bivalent gene expression during embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation.

When KAT6B was knocked out in embryonic stem cells, the cells showed diminished differentiation potential to form neurons when compared to unaltered controls. The team showed that this was caused by a failure to properly regulate the expression of bivalent genes, indicating that KAT6B contributes to the poised state of bivalent genes, ensuring their proper activation during ESC differentiation.

Dr Philipp Voigt, a tenure-track group leader in the Institute’s Epigenetics research programme, commented: “Our research provides insight into a long-standing paradigm in the regulation of developmental gene expression, revealing a key mechanism that has so far eluded experimental scrutiny. It also uncovers a new layer of histone-based regulation, suggesting that bivalency is much more complex than originally thought. We are excited to now figure out what additional layers of regulation exist and how these contribute to poising and the control of developmental gene expression.

“I’d like to thank everyone involved in this work, including colleagues from my lab in Babraham and the Bioinformatics team, and my former lab in Edinburgh and the proteomics core at the University of Edinburgh.”

END

Uncovering how developmental genes are held in a poised state

How intricate molecular interactions establish responsiveness to gene expression cues that shape development

2025-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Multimillion-pound research project aims to advance production of next-generation sustainable packaging

2025-02-06

A multimillion-pound research project, called SustaPack, aims to overcome manufacturing challenges for the next generation of sustainable, paper-based packaging for liquids. Backed by a £1 million grant from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) as part of UKRI’s co-investing programme, packaging technology company Pulpex Ltd has joined forces with the University of Surrey to refine its manufacturing processes to provide a viable solution to plastic pollution.

Contributing matching support towards the project, Pulpex has already made significant strides in the development of its patented technology, ...

‘Marine Prosperity Areas’ represent a new hope inconservation

2025-02-06

Could 2025 be the year marine protection efforts get a “glow up”? According to a team of conservation-minded researchers, including Octavio Aburto of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the moment has arrived.

In a new study published Feb. 6 in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, Aburto and a multinational team of marine scientists and economists unveil a comprehensive framework for Marine Prosperity Areas, or MPpAs. With a focus on prosperity—the condition ...

Warning signs may not be effective to deter cannabis use in pregnancy: Study

2025-02-06

PISCATAWAY, NJ – Warning signs at dispensaries about the potential health effects of cannabis use in pregnancy may not be effective, according to a new report in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, based at Rutgers University. In fact, those who are pregnant and using cannabis may actually distrust the content of warning signs altogether.

“Mandatory warning signs aren’t working,” says lead researcher Sarah C. M. Roberts, DrPH, of the University of California, San Francisco. In fact, some of the respondents “saw the signs as having stigmatizing or negative effects on pregnant people who use ...

Efforts to find alien life could be boosted by simple test that gets microbes moving

2025-02-06

Finding life in outer space is one of the great endeavors of humankind. One approach is to find motile microorganisms that can move independently, an ability that is a solid hint for life. If movement is induced by a chemical and an organism moves in response, it is known as chemotaxis.

Now, researchers in Germany have developed a new and simplified method for inducing chemotactic motility in some of Earth’s smallest life forms. They published their results in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

“We tested three types of microbes – two bacteria and one type of archaea – and found that they all moved toward a chemical called L-serine,” ...

Study shows some species are susceptible to broad range of viruses

2025-02-06

A study of fruit flies shows some species are highly susceptible to a wide range of viruses.

In the study – by the University of Exeter – 35 fruit fly species were exposed to 11 different viruses of diverse types.

As expected, fly species that were less affected by a certain virus also tended to respond well to related viruses.

But the findings also show “positive correlations in susceptibility” to viruses in general. In other words, fly species that were resistant to one virus were generally resistant to others – including very different ...

How life's building blocks took shape on early Earth: the limits of membraneless polyester protocell formation

2025-02-06

One leading theory on the origins of life on Earth proposes that simple chemical molecules gradually became more complex, ultimately forming protocells—primitive, non-living structures that were precursors of modern cells. A promising candidate for protocells is polyester microdroplets, which form through the simple polymerisation of alpha-hydroxy acids (αHAs), compounds believed to have accumulated on early Earth possibly formed by lightning strikes or delivered via meteorites, into protocells, followed by simple rehydration ...

Survey: Many Americans don’t know long-term risks of heart disease with pregnancy

2025-02-06

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. have risen 140% over the past three decades with heart disease a major cause, according to the American Heart Association. A new national survey commissioned by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center found that many Americans are not aware of the long-term risks of heart disease with pregnancy and the critical care needed before, during and after pregnancy.

“During pregnancy there are a lot of different hormone shifts that happen to accommodate growth of the baby and health of the mom. The result is that the mom’s heart rate increases along with the amount ...

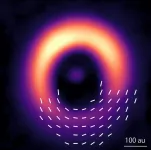

Dusting for stars’ magnetic fingerprints

2025-02-06

For the first time astronomers have succeeded in observing the magnetic field around a young star where planets are thought to be forming. The team was able to use dust to measure the three-dimensional structure “fingerprint” of the magnetic field. This will help improve our understanding of planet formation.

Planets form in turbulent disks of gas and dust called protoplanetary disks around young stars. It is thought that the first step in planet formation is dust grains colliding and sticking together. The movement of ...

Relief could be on the way for UTI sufferers dealing with debilitating pain

2025-02-06

Relief could be on the way for UTI sufferers dealing with debilitating pain

New insights into what causes the painful and disruptive symptoms of urinary tract infections (UTIs) could offer hope for improved treatment.

UTIs are one of the most prevalent bacterial infections globally, with more than 400 million cases reported every year. Nearly one in three women will experience UTIs before the age of 24, and many elderly people and those with bladder issues from spinal cord injuries can experience multiple UTI’s in a single year.

Findings from a new study led by Flinders University’s ...

Testing AI with AI: Ensuring effective AI implementation in clinical practice

2025-02-06

Using a pioneering artificial intelligence platform, Flinders University researchers have assessed whether a cardiac AI tool recently trialled in South Australian hospitals actually has the potential to assist doctors and nurses to rapidly diagnose heart issues in emergency departments.

“AI is becoming more common in healthcare, but it doesn’t always fit in smoothly with the vital work of our doctors and nurses,” says Flinders University’s Dr Maria Alejandra Pinero de Plaza, who led the research.

“We need to confirm these systems are trustworthy and work ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] Uncovering how developmental genes are held in a poised stateHow intricate molecular interactions establish responsiveness to gene expression cues that shape development