(Press-News.org) University of Virginia Cancer Center researchers have explained the failure of immune checkpoint therapy for ovarian cancer by discovering how gut bacteria interfere with the treatment. Doctors may be able to use the findings to overcome this treatment failure and save the lives of thousands of women every year.

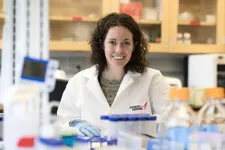

The new discovery, from the lab of UVA’s Melanie Rutkowski, PhD, speaks to the surprising ways that the microbiome – the collection of organisms that live on and inside our bodies – is vital not only to maintain health but for the effectiveness of medical treatments.

As a leading microbiome researcher, Rutkowski is excited about the potential of her field to improve care not just for ovarian cancer but for many other cancers. She has already shown, for example, how an unhealthy gut microbiome helps breast cancer spread. “As soon as we are born, the gut microbiome is critical for educating our immune system so that diseases are controlled and that we are not damaged in the process by an over exuberant immune response,” she said. “We and others are discovering the far-reaching impact that microbiome/immune cell interactions have on almost every aspect of our being, from influencing metabolic health, organ health and even the relationship between the gut and the brain. This is why it is critically important to understand how the relationship between our microbiome and immune system changes during a disease like cancer, as this research could uncover novel therapies capable of helping the immune system kill cancer cells.”

Targeting Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer kills more than 10,000 American women every year, making it the deadliest gynecological malignancy in the United States. Despite improvements in the clinical management of the disease, survival has improved very little during the past several decades. Doctors treating patients with ovarian cancer had been excited about the potential of immune checkpoint therapy – a form of immunotherapy that enhances the immune system’s ability to destroy cancer – only to find that the ovarian tumors were stubbornly resistant. This treatment approach is improving outcomes for patients with melanoma, bladder cancer and other cancers, so what is different about ovarian cancer?

Rutkowski and her team have finally found answers, and they found them in the tiny propellers bacteria use to move. These propellers, called flagella, are hairlike structures made of a material called flagellin. It is flagellin, the researchers found, that is the key to why immune checkpoint therapy does not help ovarian cancer patients as it does for patients with other types of cancer.

In ovarian cancer, Rutkowski and her team determined, bacteria and the flagellin they contain disrupt the success of the immune checkpoint treatment. The flagellin causes chaotic cellular communications that prevent immune cells from finding their way into and around the ovarian tumors. “We found that ovarian tumors enhance the ability of flagellin from the gut to get into the tumor environment, where they normally should not be,” Rutkowski said. “Because of the gut leakage, immune cells that recognize flagellin become reprogrammed to support tumor growth instead of supporting the killing of tumors during immune therapy.”

With the discovery, the tumors’ defenses could become their Achilles’ heel. The researchers found that, in early lab tests, they could block the chaotic signaling caused by the flagellin to restore the effectiveness of immune checkpoint therapy. “In mice whose immune cells that lack the ability to recognize flagellin, immune therapy induced long-term control of ovarian tumor growth in almost 80% of animals,” Rutkowski said. “That we observed this response using multiple aggressive ovarian cancer cell lines suggests that inhibiting this pathway has potential to enhance clinical outcomes for ovarian cancer patients.”

While much more research will need to be done, Rutkowski’s findings suggest we may yet have a way to turn immune checkpoint therapy into a powerful tool against ovarian cancer and, ultimately, save lives.

“The idea that immune cell recognition of bacterial flagellin leads to the failure of immune therapy is somewhat opposite to what is known about how this pathway influences immune cell behavior. We believe that there is a unique reason why flagellin inhibits immune therapy response for ovarian cancer specifically, which is an area we are actively investigating,” said Rutkowski, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology. “The survival outcomes we are achieving in mice that lack the ability to recognize flagellin are extraordinary, especially if we manage to translate these observations into the clinic. I am very hopeful that this work will help to establish a dialogue about the potential that inhibiting the ability of immune cells to recognize bacterial flagellin may have for ovarian cancer patients.”

Rutkowski’s cutting-edge ovarian cancer research is part of UVA’s sweeping effort, called the TransUniversity Microbiome Initiative, to better understand and harness the microbiome to improve human health.

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in Cancer Immunology Research. The research team consisted of Mitchell T. McGinty, Audrey M. Putelo, Sree H. Kolli, Tzu-Yu Feng, Madison R. Dietl, Cara N. Hatzinger, Simona Bajgai, Mika K. Poblete, Francesca N. Azar, Anwaruddin Mohammad, Pankaj Kumar and Rutkowski. The scientists have no financial interest in the work.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, grant R01CA253285, with personnel support from the American Cancer Society, UVA Cancer Center and UVA’s Beirne B. Carter Center for Immunology Research.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

Ovarian cancer discovery could turn failed treatment into lifesaver

2025-02-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

DNA methylation clocks may require tissue-specific adjustments for accurate aging estimates

2025-02-12

“Our results suggest that forensic applications of DNAm clocks using non-blood tissue types will provide age estimates that are not as accurate as predictions based on blood, especially if using clocks algorithms trained on blood samples.”

BUFFALO, NY—February 12, 2025 — A new research paper was published in Aging (Aging-US) on January 3, 2025, in Volume 17, Issue 1, titled “Characterization of DNA methylation clock algorithms applied to diverse tissue types.”

Researchers ...

Tidal energy measurements help SwRI scientists understand Titan’s composition, orbital history

2025-02-12

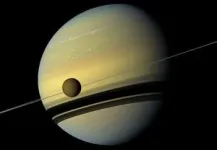

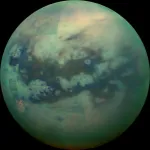

SAN ANTONIO — February 12, 2025 —Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) scientists are studying Saturn’s moon Titan to assess its tidal dissipation rate, the energy lost as it orbits the ringed planet with its massive gravitational force. Understanding tidal dissipation helps scientists infer many other things about Titan, such as the makeup of its inner core and its orbital history.

“When most people think of tides they think of the movement of the oceans, in and out, with the passage of the Moon overhead, said Dr. Brynna Downey. “But that is just because water moves ...

Data-driven networks influence convective-scale ensemble weather forecasts

2025-02-12

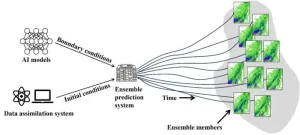

To effectively present the uncertainty of convective-scale weather forecasts, convective-scale ensemble prediction systems have been developed at major operational centers, whose lateral boundary conditions are usually provided by global numerical weather models. Recently, the emergence of AI weather models has provided a new approach to driving convective-scale ensemble prediction systems. AI weather models can produce forecasts for the next 7 to 10 days in just a few minutes, which is around 10,000 times faster than numerical weather models. However, the performance of using the ...

Endocrine Society awards Baxter Prize to innovator in endocrine cancer drug discovery

2025-02-12

WASHINGTON—Donald Patrick McDonnell, Ph.D., has been awarded the Endocrine Society’s John D. Baxter Prize for Entrepreneurship for discovering hormone therapies for treating breast and prostate cancer, the Society announced today.

The John D. Baxter Prize for Entrepreneurship was established to recognize the extraordinary achievement of bringing an idea, product, service, or process to market. This work ultimately elevates the field of endocrinology and positively impacts the health of patients.

McDonnell is a professor at Duke University School ...

Companies quietly switching out toxic product ingredients in response to California law

2025-02-12

A new study by Silent Spring Institute and University of California, Berkeley shows how laws that promote greater transparency around harmful chemicals in products can shift markets toward safer products.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, focused on California’s right-to-know law called Proposition 65, or Prop 65. Under the law, the state of California maintains a list of approximately 900 chemicals known to cause cancer, birth defects, or reproductive harm. Companies that sell products in California are required to warn people if their products could expose them to harmful ...

Can math save content creators? A new model proposes fairer revenue distribution methods for streaming services

2025-02-12

As more consumers turn to subscription-based platforms, the distribution of revenue in streaming services has become a crucial issue in the digital economy. Content creators and artists argue that the current models are opaque, frequently neglecting the needs of creators. In response, researchers at UMH have proposed a model based on three allocation rules that could be applied according to various fairness criteria.

"Our model is based on three main approaches: the equal division rule, which divides revenue equally among services; the proportional rule, which allocates revenue according ...

Study examines grief of zoo employees and volunteers across the US after animal losses

2025-02-12

A collaboration of researchers from Colorado State University and Denver Zoo Conservation Alliance surveyed zoo employees and volunteers across the US about their experiences of burnout and grief related to zoo animal losses.

Their latest study has found that poor grief support in some US zoos leaves staff feeling limited empathy from leadership, burned out, and unable to openly express their grief after the death of an animal to which they had formed a close emotional bond.

The research, published in the journal ...

National study underway to test new mechanical heart pump

2025-02-12

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A cardiac surgery and heart failure team at the University of Michigan implanted a novel mechanical heart pump into a patient as part of a clinical trial that will compare it to the only device currently used to treat end-stage heart failure.

“This trial presents an opportunity to assess novel technology as we explore a potential new treatment for advanced heart failure — a life-threatening condition with extremely limited therapeutic opportunities available,” said Francis Pagani, M.D., Ph.D., national ...

Antarctica’s only native insect’s unique survival mechanism

2025-02-12

Picture an Antarctic animal and most people think of penguins, but there is a flightless midge, the only known insect native to Antarctica, that somehow survives the extreme climate. How the Antarctic midge (Belgica antarctica) copes with freezing temperatures could hold clues for humans about subjects like cryopreservation, but there remain many mysteries about the tiny insect.

One mystery appears to have been solved by an Osaka Metropolitan University-led international research team. Graduate School of Science Professor Shin G. Goto and Dr. Mizuki Yoshida, a graduate student at the time of the research who is now a postdoc at Ohio State University, found ...

How Earth's early cycles shaped the chemistry of life

2025-02-12

A new study explores how complex chemical mixtures change under shifting environmental conditions, shedding light on the prebiotic processes that may have led to life. By exposing organic molecules to repeated wet-dry cycles, researchers observed continuous transformation, selective organization, and synchronized population dynamics. Their findings suggest that environmental factors played a key role in shaping the molecular complexity needed for life to emerge. To simulate early Earth, the team subjected chemical mixtures to repeated wet-dry cycles. Rather than reacting randomly, the molecules organized themselves, evolved over time, and followed predictable patterns. This challenges ...