(Press-News.org) Images

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Tropical forests are massive biodiversity storehouses. While these rich swathes of land constitute less than one-tenth of Earth’s surface, they harbor more than 60% of known species. Among them is a higher concentration of endangered species than anywhere else on Earth.

However, these regions are also under immense pressure, as tropical land is rapidly being transformed for industrial and agricultural purposes.

Worldwide, regional governments and international groups are establishing new protected areas to slow further loss of threatened species. However, new research appearing in the journal PLOS Biology demonstrates that this strategy may not be enough on its own to reverse, or even stop, these regions’ declining biodiversity.

Michigan State University Assistant Professor Lydia Beaudrot, an ecologist in the Department of Integrative Biology, was a key contributor to the study. Beaudrot leads a research group whose focus is on quantifying data-driven insights into the ecology and conservation of tropical mammals.

This paper brought together an international cohort of tropical wildlife researchers. Together, they assessed how tropical mammalian communities are affected by the activity of nearby humans — from the impact of simple coexistence to widespread environmental change.

“We found that tropical forests near more people have fewer mammal species. It suggests that some species do not survive even when forests are protected, such as in national parks,” Beaudrot explained.

Activities such as clear-cutting or other transformations of land present some of the most destructive threats to habitats. But even persistent human activity, including hunting and simply living adjacent to protected areas, can decrease some animals’ ability to thrive in protected zones, the authors argued.

Near the not-so-quiet village

This effect, termed “anthropogenic extinction filtering,” demonstrates that human activity outside of protected areas is dramatically reshaping the forest communities within them.

Across tropical forests spanning three continents — South America, Africa and Asia — the researchers measured how varied and dense the populations of mammals were within these regions using an unprecedented dataset comprised of over 2,000 cameras across tropical forests worldwide.

The images gathered came in part from a network of 17 sites across the tropics established as the Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring Network which is composed of a diverse group of conservationists and research collaborators.

Ilaria Greco, a doctoral candidate at the University of Florence and lead author on the study, forged connections with an even broader international cohort of wildlife researchers to facilitate the exchange of data not included in the Wildlife Insights database. This collaboration paved the way for the largest-ever study of its kind, encompassing 37 total locations — more than double the sites available through Wildlife Insights.

This endeavor yielded long-term data on 239 species of mammals, enabling researchers to examine how these numbers changed where human population density and habitat disturbance in nearby areas differed. Sites in the study ranged from large, continuous forested regions to highly fragmented forest ecosystems.

In addition to the critical importance of protected areas, Beaudrot noted that additional conservation measures, such as forest restoration, are essential to protect tropical mammals.

The researchers developed a model that integrated remote-sensing data — information gathered from aerial imagery — with images from trail cameras to better understand how human presence impacted mammal communities in protected areas.

“Through a massive collaboration among many researchers, we used the largest dataset to date to test how habitat loss and human density affect tropical forest wildlife,” Beaudrot said.

The model predicted that for every 16 humans within a square kilometer of a protected area, mammal species could decrease by as much as 1%.

Where the buffer zone for these protected areas is negligible, the activity along their edges can reshape forest communities.

Land change in tropical forests means that nearly 70% of tropical forest habitats are within one kilometer of a forest’s edge — where interactions with humans or infrastructure becomes likely.

Mammal communities were also negatively impacted by forest loss and fragmentation within 50 kilometers, or about 31 miles, of their forested habitats.

“It is not just the protected area that matters for biodiversity conservation but also what is outside the protected area,” Beaudrot said.

Unprecedented understanding

“Until recently, we have not had high-quality data at a global scale to measure how people affect the number of mammal species and how widely they occur within tropical forests,” Beaudrot said.

This research provides the most comprehensive picture to date of how human activity contributes to declining biodiversity in some of the most species-rich regions of the world.

While protected areas are critically important for conservation, the existence of protected areas on their own may not be enough to guarantee that threatened and endangered species are able to survive.

Current initiatives, including the United Nations’ Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which are meant to stop or reverse human-caused extinction and ecosystem destruction, may fall short of these goals, the authors warned.

Therefore, to create more effective protected areas, the authors suggested that reducing the effects of humans outside protected area borders is critical. They note that restoring habitat outside the protected areas widens the zone between humans and tropical mammals, helping bolster biodiversity.

Rather than protecting isolated patches of land, the authors noted that tropical mammals may stand a better chance if protected areas become more widespread and connected, creating broader uninterrupted regions for animals to persist in.

Greco, who led the project and is a former visiting scholar in Beaudrot’s lab, now works as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Francesco Rovero, an associate professor of ecology at the University of Florence and a long-time collaborator of Beaudrot’s.

According to Greco, the team’s results suggest the existence of “anthropogenic extinction filtering acting on mammals in tropical forests, whereby human overpopulation has driven the most sensitive species to local extinction while remaining ones are able to persist, or even thrive, in highly populated landscapes and mainly depend on habitat cover.”

“The study warns that conservation of many mammals in tropical forests depends on mitigating the complex detrimental effects of anthropogenic pressures well beyond protected area borders,” said Rovero.

This study was first published on Feb. 13 in PLOS Biology. Parts of this story have been adapted from a release prepared by the journal.

By Caleb Hess

###

Michigan State University has been advancing the common good with uncommon will for 170 years. One of the world’s leading public research universities, MSU pushes the boundaries of discovery to make a better, safer, healthier world for all while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 400 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the web, go to MSUToday or x.com/MSUnews.

END

Protected habitats aren’t enough to save endangered mammals, MSU researchers find

2025-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists find new biomarker that predicts cancer aggressiveness

2025-02-13

HOUSTON ― Using a new technology and computational method, researchers from Fred Hutch Cancer Center and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have uncovered a biomarker capable of accurately predicting outcomes in meningioma brain tumors and breast cancers.

In the study, published today in Science, the researchers discovered that the amount of a specific enzyme, RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII), found on histone genes was associated with tumor aggressiveness and recurrence. Hyper-elevated levels of RNAPII on these histone genes indicate cancer over-proliferation and potentially contribute to chromosomal changes. These findings point to the use of a new genomic technology as ...

UC Irvine astronomers gauge livability of exoplanets orbiting white dwarf stars

2025-02-13

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 13, 2025 — Among the roughly 10 billion white dwarf stars in the Milky Way galaxy, a greater number than previously expected could provide a stellar environment hospitable to life-supporting exoplanets, according to astronomers at the University of California, Irvine.

In a paper published recently in The Astrophysical Journal, a research team led by Aomawa Shields, UC Irvine associate professor of physics and astronomy, share the results of a study comparing the climates of exoplanets at two different stars. One is a hypothetical white dwarf that’s passed through much of its life cycle and is on a slow path ...

Child with rare epileptic disorder receives long-awaited diagnosis

2025-02-13

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan NRI) at Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor Genetics and collaborating institutions provided a long-awaited and rare genetic diagnosis in a child with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a type of developmental epileptic encephalopathy (DEE), associated with a severe, complex form of epilepsy and developmental delay.

Their recent study reports that a highly complex rearrangement of fragments from chromosomes 3 and 5 altered the typical organization of genes in the q14.3 region of chromosome ...

WashU to develop new tools for detecting chemical warfare agent

2025-02-13

Mustard gas, also known as sulfur mustard, is one of the most harmful chemical warfare agents, causing blistering of the skin and mucous membranes on contact. Chemists at Washington University in St. Louis have been awarded a $1 million contract with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) to develop a new way to detect the presence of this chemical weapon on the battlefield.

As with many chemical threats, quick identification of sulfur mustard is key to minimizing its damage, according to Jennifer Heemstra, the Charles Allen Thomas Professor of Chemistry in Arts & Sciences and principal investigator of the new DTRA grant.

“It’s ...

Tufts researchers discover how experiences influence future behavior

2025-02-13

Neuroscientists have new insights into why previous experiences influence future behaviors. Experiments in mice reveal that personal history, especially stressful events, influences how the brain processes whether something is positive or negative. These calculations ultimately impact how motivated a rodent is to seek social interaction or other kinds of rewards.

In a first of its kind study, Tufts University School of Medicine researchers demonstrate that interfering with the neural circuits responsible ...

Engineers discover key barrier to longer-lasting batteries

2025-02-13

Lithium nickel oxide (LiNiO2) has emerged as a potential new material to power next-generation, longer-lasting lithium-ion batteries. Commercialization of the material, however, has stalled because it degrades after repeated charging.

University of Texas at Dallas researchers have discovered why LiNiO2 batteries break down, and they are testing a solution that could remove a key barrier to widespread use of the material. They published their findings online Dec. 10 in the journal Advanced Energy Materials.

The team plans first to manufacture LiNiO2 batteries in the lab and ...

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2025

2025-02-13

WASHINGTON — The Society for Neuroscience (SfN) has selected 10 members from a highly competitive applicant pool to participate in the Society’s annual Capitol Hill Day on March 11–13, 2025. The 10 Early Career Policy Ambassadors (ECPAs), representing many career stages and geographic locations, were chosen for their dedication to advocating for the scientific community, their desire to learn more about effective means of advocacy, and their experience as leaders in their labs and community.

The ambassadors are:

Izan Chalen, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Nicole D’Souza, University of California, Riverside

Lana Ruvolo Grasser, PhD, Department ...

YOLO-Behavior: A new and faster way to extract animal behaviors from video

2025-02-13

Collecting video data is the long-established way biologists collect data to measure the behaviour of animals and humans. Videos might be taken of human subjects sitting in front of a camera while eating in a group in the University of Konstanz, or researchers using cameras to measure how often house sparrow parents visit their nests on Lundy Island, UK. All these video datasets have one thing in common: after collecting them, researchers need to painstakingly watch each video, manually mark down who, where and when each behaviour of interest happens—a process known as “annotation”. ...

Researchers identify a brain circuit for creativity

2025-02-13

KEY TAKEAWAYS

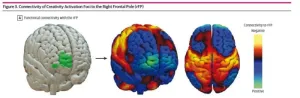

Brigham researchers analyzed data from 857 patients across 36 fMRI brain imaging studies and mapped a common brain circuit for creativity.

They derived the circuit in healthy individuals and then predicted which locations of brain injury and neurodegenerative disease might alter creativity.

The study found that changes in creativity in people with brain injury or neurodegenerative disease may depend on the location of injury in reference to the creativity circuit.

A new study led by ...

Trends in obesity-related measures among U.S. children, adolescents, and adults

2025-02-13

About The Study: From 2013-2014 to August 2021-August 2023, there were small increases in the percentage of children and adolescents with obesity, as well as in adults with severe obesity (but not obesity). There were no other significant changes in obesity-related measures, including waist circumference. This period included the COVID-19 pandemic; a study using electronic health records found a small increase in mean weight among adults during the pandemic.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Samuel D. Emmerich, DVM, email semmerich@cdc.gov.

To access ...