(Press-News.org) Feb. 24, 2025

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Contact: Emilie Lorditch: 517-355-4082, lorditch@msu.edu

Images

MSU researchers use open-access data to study climate change effects in 24,000 US lakes

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Each summer, more and more lake beaches are forced to close due to toxic algae blooms. While climate change is often blamed, new research suggests a more complex story: climate interacts with human activities like agriculture and urban runoff, which funnel excess nutrients into the water. The study sheds light on why some lakes are more vulnerable than others and how climate and human impacts interact — offering clues to why the problem is getting worse.

Michigan State University researchers discovered key climate-related patterns in algal biomass levels and change through time for freshwater lakes. They used novel methods to create and analyze long-term datasets from open-access government resources and from satellite remote sensing. This research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides crucial insights into how climate affects lake ecosystems.

The team studied chlorophyll levels, a measure of algal biomass, in lakes across the U.S. from the last 34 years. Climate change is thought to intensify lake algal blooms and increase the likelihood of “regime shifts,” or sudden and long-lasting changes in the structure and function of an ecosystem.

“Our research demonstrates that the relationship between climate change and algal biomass is more complex than previously understood,” said Patricia Soranno, a professor in the MSU College of Natural Science and one of the co-lead authors of this study. “While climate change is a significant driver, we found that the impacts are not always gradual or predictable. To effectively manage and protect lakes, we need to study these effects in many different local and regional contexts.”

Traditionally, researchers have struggled to predict changes in algal biomass using available lake sampling data. To overcome this challenge, the MSU team, led by Soranno and Patrick Hanly, a quantitative ecologist in the MSU College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, developed a novel approach. Leveraging over 30 years of publicly available satellite imagery, researchers used machine learning to create an unprecedented dataset of algal biomass in 24,452 U.S. lakes. The team combined this dataset with LAGOS-US, a large geospatial research platform that describes lake features of the U.S. that Soranno and Kendra Spence Cheruvelil, dean of MSU’s Lyman Briggs College and others have spent years developing. Their analysis is one of the first to document a causal link between climate and algae.

They found that climate caused changes in algal biomass in about a third of tested lakes (34%), but in unexpected ways. For lakes with climate-related changes, only 13% were prone to regime shifts, only 4% increased in productivity, whereas 71% of them had abrupt, but only temporary changes.

This lack of a general and sustained change may appear reassuring. However, annual abrupt changes in biomass that were detected have not typically been measured, leaving these abrupt changes understudied. This has led to gaps in understanding of the effects of climate on water quality such as algal biomass. Luckily, the methods used in this paper can capture these abrupt fluctuations that traditional approaches might miss.

This large-scale approach also uncovered variability in climate-driven algal responses that depend on environmental conditions and the level of human disturbance. Lakes with low to moderate human impacts were more likely to respond to climate, while lakes already under heavy human pressures, like increased nutrient input from agriculture, were less likely linked to climate.

“Our findings emphasize the importance of considering both climate and other measures of human impacts when assessing the health of lakes, especially over decades,” said Lyman Briggs College. “This research provides a crucial foundation for developing effective strategies to mitigate the impacts of these stressors and protect the valuable resources that lakes provide.”

###

Michigan State University has been advancing the common good with uncommon will for 170 years. One of the world’s leading public research universities, MSU pushes the boundaries of discovery to make a better, safer, healthier world for all while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 400 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the web, go to MSUToday or x.com/MSUnews.

END

MSU researchers use open-access data to study climate change effects in 24,000 US lakes

2025-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

More than meets the eye: An adrenal gland tumor is more complex than previously thought

2025-02-24

Fukuoka, Japan - Kyushu University researchers have uncovered a surprising layer of complexity in aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs)—adrenal gland tumors that drive high blood pressure. Using cutting-edge analysis techniques, they discovered that these tumors harbor at least four distinct cell types, including ones that produce cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone. Published in the week beginning 24 February in PNAS, their findings not only explain why some patients with APAs develop unexpected health issues, like weakened bones, but also pave the way toward new treatment strategies.

“Currently, the only ...

Origin and diversity of Hun Empire populations

2025-02-24

The Huns suddenly appeared in Europe in the 370s, establishing one of the most influential although short-lived empires in Europe. Scholars have long debated whether the Huns were descended from the Xiongnu. In fact, the Xiongnu Empire dissolved around 100 CE, leaving a 300-year gap before the Huns appeared in Europe. Can DNA lineages that bridge these three centuries be found?

To address this question, researchers analyzed the DNA of 370 individuals that lived in historical periods spanning around 800 years, from 2nd century BCE to 6th century CE, encompassing sites in the Mongolian steppe, Central Asia, and the Carpathian Basin of Central Europe. ...

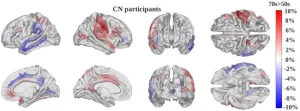

New AI model measures how fast the brain ages

2025-02-24

A new artificial intelligence model measures how fast a patient’s brain is aging and could be a powerful new tool for understanding, preventing and treating cognitive decline and dementia, according to USC researchers.

The first-of-its-kind tool can non-invasively track the pace of brain changes by analyzing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Faster brain aging closely correlates with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, said Andrei Irimia, associate professor of gerontology, biomedical engineering, quantitative ...

This new treatment can adjust to Parkinson's symptoms in real time

2025-02-24

Starting today, people with Parkinson’s disease will have a new treatment option, thanks to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of groundbreaking new technology.

The therapy, known as adaptive deep brain stimulation, or aDBS, uses an implanted device that continuously monitors the brain for signs that Parkinson’s symptoms are developing. When it detects specific patterns of brain activity, it delivers precisely calibrated electric pulses to keep symptoms at bay.

The FDA approval covers two treatment algorithms that run on a device made by Medtronic, a medical device company. Both work by monitoring the same part of the brain, called the subthalamic nucleus. ...

Bigger animals get more cancer, defying decades-old belief

2025-02-24

Elephants, giraffes, pythons and other large species have higher cancer rates than smaller ones like mice, bats, and frogs, a new study has shown, overturning a 45-year-old belief about cancer in the animal kingdom.

The research, conducted by researchers from the University of Reading, University College London and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, examined cancer data from 263 species across four major animal groups - amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles. The findings challenge "Peto's paradox," a longstanding idea based on observations from 1977 that suggested ...

As dengue spreads, researchers discover a clue to fighting the virus

2025-02-24

LA JOLLA, CA—Children who experience multiple cases of dengue virus develop an army of dengue-fighting T cells, according to a new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI).

The findings, published recently in JCI Insights, suggest that these T cells are key to dengue virus immunity. In fact, most children who experienced two or more dengue infections showed very minor symptoms—or no symptoms at all—when they caught the virus again.

"We saw a significant T cell response in children who had been infected more than once before," says study leader and LJI Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D.

Dengue virus infects up ...

Teaming up tiny robot swimmers to transform medicine

2025-02-24

Smart artificial microswimmers—small robots that resemble microorganisms like bacteria or human sperm—could potentially be used for targeted drug delivery, minimally invasive surgery, and even in fertility treatments.

These types of complicated tasks won’t be accomplished by a single microswimmer. Multiple swimmers will be necessary; however, it’s unclear how such groups will move within the chemically and mechanically complex environment of the body’s fluids.

“We know that whenever a swimmer has a neighbor, it swims differently,” says Ebru Demir, an assistant ...

The Center for Open Science welcomes Daniel Correa and Amanda Kay Montoya to its Board of Directors

2025-02-24

(Charlottesville, VA, Feb. 24, 2025) –

The Center for Open Science (COS) is pleased to announce the appointment of Daniel Correa, Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, and Amanda Montoya, Associate Professor of Quantitative Psychology at UCLA, to the COS Board of Directors. Both will serve three-year terms from 2025 to 2027, bringing valuable expertise in science policy, innovation, research methodology, and open science advocacy.

Daniel Correa is the Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, ...

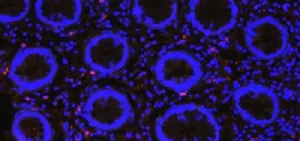

Research suggests common viral infection worsens deadly condition among premature babies

2025-02-24

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Researchers say they found that infection with a common virus that can be transmitted from mother to fetus before birth significantly worsens an often-fatal complication of premature birth called necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in experiments with mice.

The research team, led by Johns Hopkins Children’s Center investigators and funded by the National Institutes of Health, says the new findings advance the search for better treatments for NEC — a relatively rare condition, but still the most common emergency intestinal complication in preemies.

A report on the study published Feb. 13 in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology ...

UC Irvine scientists invent new drug candidates to treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria

2025-02-24

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 24, 2025 — There’s an arms race in medicine – scientists design drugs to treat lethal bacterial infections, but bacteria can evolve defenses to those drugs, sending the researchers back to square one. In the Journal of the American Chemical Society, a University of California, Irvine-led team describes the development of a drug candidate that can stop bacteria before they have a chance to cause harm.

“The issue with antibiotics is this crisis of antibiotic ...