(Press-News.org)

Global partnerships that embed scientific research into clinical care are revolutionising the diagnosis and treatments for children with rare genetic diseases, according to a new report.

The white paper found despite advances in genomic technologies, which can detect rare genetic diseases within days, there remained significant challenges to ensuring this leads to improved child health outcomes. But global collaborations, such as the International Precision Child Health Partnership (IPCHiP), using evidence-based approaches to inform decisions in real-time, are overhauling patient care.

The paper was led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), Boston Children's Hospital, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute for Child Health (GOS ICH) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH).

Rare diseases are becoming increasingly common affecting about 300 million people globally. One in three children with a rare disease will die before the age of five.

MCRI Dr Katherine Howell said identifying a genetic diagnosis was the first step in delivering precision medicine.

More than 70 per cent of rare diseases, now totalling up to 10,000, have a genetic cause.

“Advances in genomic technologies, especially exome sequencing and genome sequencing, and integrating these tests into clinical settings have considerably improved diagnostic yields for rare diseases,” Dr Howell said.

“A genetic diagnosis often informs clinical management, treatment, prognosis and access to resources and support. Over 600 rare disease genes that often emerge in childhood and cause severe disorders have treatment available, underscoring the urgency for improving diagnosis rates.”

The report, published in npj Genomic Medicine on Rare Diseases Day, found with limited and often inequitable access to genomic testing, wide-sweeping international efforts were needed to accelerate accurate diagnosis and implement evidence-based practice changes.

“A coordinated approach on a global scale can energise collaboration and maximise research output by building on the diverse expertise and existing efforts, reducing duplication and creating frameworks for responsible data collection and sharing,” Dr Howell said.

“Multidisciplinary collaborations are also required to connect clinicians with scientists to advance our understanding of diseases and forge partnerships with industry, foundations, and patient advocacy groups to identify opportunities for development of new therapies and rapidly translate them to the clinic.”

IPCHiP, an international consortium leveraging the medical and scientific expertise from MCRI, SickKids, Boston Children's Hospital, GOS ICH and GOSH aims to use genomic data to accelerate discovery and therapeutic options. It has recently been designated a ‘Driver Project’ of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH).

SickKids Professor Stephen Scherer said by embedding research in clinical practice, IPCHiP was generating the evidence and model needed to advance precision medicine.

“IPCHiP is the first major global clinical collaboration around genomics and precision child health,” he said. Thanks to our international partnership focused on rare diseases, we can forge innovative diagnostic solutions and work towards new treatments that improve health outcomes.”

IPCHiP’s initial flagship project, Gene-STEPS found that rapid genome sequencing was highly effective at diagnosing babies with epilepsy and lead to better, more targeted treatment options in most cases. The research, published in The Lancet Neurology, reported rapid genome sequencing had a high diagnostic rate of 43 per cent for infantile epilepsy, supporting the need for greater access to the cutting-edge technology in clinical care.

MCRI Professor John Christodoulou said a top priority of IPCHiP was exploring approaches that could overcome challenges around how data was currently shared, accessed and used international.

“The team is using the Gene-STEPS findings to establish a data network that will allow shared analysis of clinical and genomic information generated from collaborative projects for any paediatric rare disease,” he said.

“Genomic data obtained in childhood and from reproductive carrier screening will help us in the future to tackle the common health issues such as heart disease and cancer.”

IPCHiP is expanding its work on rapid genomic testing to other genetic conditions that could benefit from a prompt diagnosis. Its next cohort, GEMStone, will focus on newborns with hypotonia, where a baby is born with low muscle tone, which can lead to difficulties in feeding, holding their head up and achieving developmental milestones.

Publication: Katherine B. Howell, Susan M. White, Amy McTague, Alissa M. D’Gama, Gregory Costain, Annapurna Poduri, Ingrid E Scheffer, Vann Chau, Lindsay D. Smith, Sarah EM Stephenson, Monica Wojcik, Andrew Davidson, Neil Sebire, Piotr Sliz, Alan H. Beggs, Lyn S Chitty, Ronald D. Cohn, Christian R. Marshall, Nancy C. Andrews, Kathryn N North, J. Helen Cross, John Christodoulou and Stephen W. Scherer. ‘International Precision Child Health Partnership (IPCHiP): an initiative to accelerate discovery and improve outcomes in rare pediatric disease,’ npj Genomic Medicine. DOI: 10.1038/s41525-025-00474-8

Available for interview:

Dr Katherine Howell, MCRI, Group Leader, Neuroscience

Professor John Christodoulou, MCRI, Theme Director, Genomic Medicine

Professor Stephen Scherer, SickKids, Chief of Research

END

Svalbard, Norway – February 27, 2025 – Researchers from Polar Bears International, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, the Norwegian Polar Institute, and the University of Toronto Scarborough reveal the first detailed look at polar bear cubs emerging from their dens, captured through nearly a decade of remote camera footage in Svalbard, Norway. This research, published today on International Polar Bear Day in the Journal of Wildlife Management, marks the first combination of satellite tracking collars with remote camera traps to answer ...

A research team led by Assistant Professor Shogo Mori and Professor Susumu Saito at Nagoya University has developed a groundbreaking method of artificial photosynthesis that uses sunlight and water to produce energy and valuable organic compounds, including pharmaceutical materials, from waste organic compounds. This achievement represents a significant step toward sustainable energy and chemical production. The findings were published in Nature Communications.

“Artificial photosynthesis involves chemical reactions ...

In 1982, the Syrian government besieged the city of Hama, killing tens of thousands of its own citizens in sectarian violence. Four decades later, rebels used the memory of the massacre to help inspire the toppling of the Assad family that had overseen the operation.

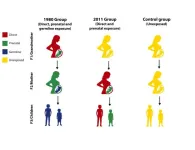

But there is another lasting effect of the attack, hidden deep in the genes of Syrian families. The grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the siege — grandchildren who never experienced such violence themselves — nonetheless bear marks of it in their genomes. ...

When faced with chronic stress, why do some people develop anxiety and depressive symptoms while others show resilience? A protein that acts as a cannabinoid receptor and is present in the structure controlling exchanges between the bloodstream and the brain could be part of the answer, according to a study published today in Nature Neuroscience.

“The protein, called cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1), is part of the blood-brain barrier, the dynamic structure that protects the brain by regulating the passage of molecules between the bloodstream and ...

A new study led by researchers at Mass General Brigham suggests a nasal spray developed to target neuroinflammation could one day be an effective treatment for traumatic brain injury (TBI). By studying the effects of the nasal anti-CD3 in a mouse model of TBI, researchers found the spray could reduce damage to the central nervous system and behavioral deficits, suggesting a potential therapeutic approach for TBI and other acute forms of brain injury. The results are published in Nature Neuroscience.

“Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of death and disability — including cognitive decline ...

Covid-19 showed us how vulnerable the world is to pandemics – but what if the next pandemic were somehow engineered? How would the world respond – and could we stop it happening in the first place?

These are some of the questions being addressed by a new initiative launched today at the University of Cambridge, which seeks to address the urgent challenge of managing the risks of future engineered pandemics.

The Engineered Pandemics Risk Management Programme aims to understand the social and biological factors that might drive an engineered pandemic and to make a major contribution ...

The researchers challenge the widespread belief that AI-induced bias is a technical flaw, arguing instead AI is deeply influenced by societal power dynamics. It learns from historical data shaped by human biases ,absorbing and perpetuating discrimination in the process. This means that, rather than creating inequality, AI reproduces and reinforces it.

“Our study highlights real-world examples where AI has reinforced existing biases.” Prof. Bircan says. “One striking case is Amazon’s AI-driven hiring tool, which was found to favor male candidates, ultimately reinforcing gender disparities in the job market. Similarly, government AI fraud detection ...

The following is a Q&A with Dr Nerea Casal García, a sports scientist focusing on sports training and performance optimization. To speak to the author, or to receive an advance copy of the paper, please write to: press@frontiersin.org The paper will be published on 27 Feb 2025 06:15 CET]

Dr Nerea Casal García is an athlete, personal coach, and injury readaptation specialist who last year completed a PhD on observational analysis in elite sports. Today, she is a professor at the Institut Nacional ...

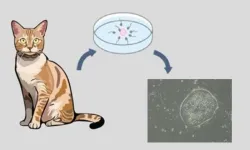

As different as they may seem, humans and cats have similar ailments, but in terms of health care, veterinary regenerative medicine is not as advanced.

A possible solution rests in embryonic stem cells, which can differentiate into various types of cells and be transplanted to restore internal damage. Further, they are characterized by their near-natural state similar to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Recent research has successfully generated feline iPS cells, but not embryonic stem cells, so research on these cell lines is essential to improve the quality ...

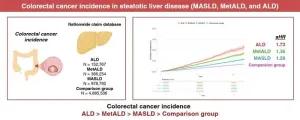

Alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are well-known risk factors for colorectal cancer (CRC). NAFLD has emerged as a heterogenous disease tightly linked to metabolic dysfunction and has been redefined under the umbrella term ‘steatotic liver disease’ (SLD). However, CRC risk variations across different SLD subgroups remain unknown. Now, researchers from Japan have discovered that the risk of CRC varies significantly among SLD subgroups, with patients with alcoholic liver disease being at higher risk.

Lifestyle-related disorders have become increasingly prevalent, representing a major health ...