(Press-News.org) More than 99% of birds can fly. But that still leaves many species that evolved to be flightless, including penguins, ostriches, and kiwi birds. In a new study in the journal Evolution, researchers compared the feathers and bodies of different species of flightless birds and their closest relatives who can still fly. They were able to determine which features change first when birds evolve to be flightless, versus which traits take more time for evolution to alter. These findings help shed light on the evolution of complex traits that lose their original function, and could even help reveal which fossil birds were flightless.

All of the flightless birds alive today evolved from ancestors who could fly and later lost that ability. “Going from something that can't fly to flying is quite the engineering challenge, but going from something that can fly to not flying is rather easy,” says Evan Saitta, a research associate at the Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the paper.

In general, there are two common reasons why birds evolve flightlessness. When birds land on an island where there aren’t predators (including mammals) that would hunt them or steal their eggs, they sometimes settle there and gradually adapt to living on the ground. Since they don’t experience evolutionary pressure to stay in flying form, they gradually lose some of the features of their skeletons and feathers that help them fly. Meanwhile, some birds’ bodies change when they evolve semi-aquatic lifestyles. Penguins, for instance, can’t fly, but they swim in a way that’s akin to “flying underwater.” Their feathers and skeletons have changed accordingly.

Saitta is a paleontologist who often studies non-avian dinosaurs (the branches of the dinosaur family tree that do not include modern birds). However, when he arrived at the Field Museum for a postdoctoral fellowship, he was struck by the Field’s collections of over half a million birds.

“I suddenly had access to all these modern birds, and it made me wonder, ‘What happens when a bird loses the ability to fly?’” says Saitta. “And because I'm not an ornithologist, I went in and measured as many features of as many different feathers as I could. So it was a highly exploratory study in that sense.”

Saitta examined the preserved skins of thirty species of flightless birds and their closest flighted relatives and measured a variety of the birds’ feathers, including the microscopic branching structures that make up feather plumage. He also examined specimens of other, more distantly related species to represent more of the bird family tree.

Previous research has revealed how long ago different species of flightless birds branched off from their flying relatives. The ancestors of ostriches, for example, lost the ability to fly much longer ago than the ancestors of a flightless South American duck called the Fuegian steamer. Saitta found that these species’ feathers are very different. “Ostriches have been flightless for so long that their feathers are no longer optimized for being aerodynamic,” says Saitta. As a result, their feathers have become so long and shaggy that they're sometimes used in feather dusters and boas. But even though Fuegian streamers can no longer fly, they lost this ability relatively recently, and their feathers remain similar to those of their flying cousins.

Saitta says he was surprised by how long it seemed to take flightless birds to lose the feather features that would have helped them fly. It didn’t seem to make sense why a flightless species would “waste” energy growing a bunch of feathers optimized for an activity that it no longer did, or why feathers no longer required for flight wouldn’t be freed up to evolve into a wide variety of forms. However, Saitta says, his postdoctoral advisor, Field Museum research associate and former Field curator Peter Makovicky (now at the University of Minnesota’s Bell Museum), had another perspective.

“Pete pointed out that when trying to understand why a modern bird looks the way it does, you can’t just think about natural selection or relaxation thereof. You have to also consider developmental constraints,” says Saitta. “Feathers are complex structures that have a really well-defined developmental sequence that’s hard to change. And when birds lose flight, those feather features disappear in the opposite order that they first evolved.”

When bird embryos develop feathers, those feathers increase in complexity in the same general order that those feather features first evolved in dinosaurs. After losing the ability to fly, birds lose those feather features in the opposite order that they first evolved. It’s like remodeling a house-- it’s faster and easier to change elements that went in last, like the wallpaper, than it is to tear down a load-bearing wall and rebuild it into something new.

Some more recently-evolved feather adaptations, like the asymmetry in the flight feathers that allows birds to fly, are easier to change, and thus disappear relatively quickly once birds no longer need to fly. But overall, the basic feather structure is like those load-bearing walls. It takes a lot of evolutionary time for the underlying development of a standard feather to be transformed into producing something like a plume-y ostrich feather.

Saitta and his colleagues also found that certain larger features changed relatively quickly once a lineage lost the ability to fly. “The first things to change when birds lose flight, possibly even before the flight feathers become symmetrical, is the proportion of their wings and their tails. We therefore see skeletal changes and also a change in overall body mass,” he says.

The reason behind this, says Saitta, may be the comparative “costs” to grow these features. When animals develop, it takes a lot more energy to grow bones than it does to grow feathers-- so evolution “prioritizes” changing the skeleton before the majority of the feathers.

“Let’s say a bird species lands on an island where they are able to safely live on the ground and don’t need to fly anymore. The first things to go are going to be these big, expensive bones and muscles, but feathers are cheap, so there’s less active selection to change them,” says Saitta. It’s like how if you auto-paid your $1,500 monthly rent on an old apartment that you no longer live in, that would have a bigger effect on your bank account than forgetting to cancel a $5-a-month subscription. For newly flightless birds, maintaining a flight-friendly skeleton is a bigger unnecessary cost than keeping some of their old feathers around unaltered.

Insights from this research could help scientists trying to determine whether a fossil bird, or a feathered dinosaur that isn’t part of the bird family, was able to fly. “Flight didn’t evolve overnight, and flight, or at least gliding, was possibly lost many times in extinct species, just as in surviving bird lineages. Our paper helps show the order in which birds’ bodies reflect those changes,” says Saitta. “Unless you have a fossil whose ancestors, even older fossils, have been flightless for a very long time, you might not see too many changes in their feathers. You might first want to look for changes in body mass, the relative length of the wings. Those change first, and then you can perhaps see changes in the symmetry of the feathers.”

Saitta’s research corroborates previous studies that have shown that a bird’s flight feathers become more symmetric after flight loss. “The good news is that because I came at this question from a different angle, we got results that are very consistent with a lot of the previous research, but I think maybe a little bit broader than if I had approached the question with a more specific focus,” says Saitta.

###

END

When birds lose the ability to fly, their bodies change faster than their feathers

2025-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genetic switch could help control leaf growth in poor soils

2025-02-27

A new study has identified a genetic circuit in plants that controls individual leaf growth and allows the plants to adapt to their environment. The findings could help the development of more drought-resistant crops.

Scientists from the University of Nottingham’s School of Biosciences investigated the growth of maize leaves in plants cultivated in three different soils containing differential amounts of nutrients and water. They found that microbes colonising plant leaves across these soils influence the growth of the leaves independently of the concentration of nutrients and soil properties. The findings have been published ...

Virtual breastfeeding support may expand breastfeeding among new mothers

2025-02-27

Mothers who were given access to virtual breastfeeding support (or telelactation) through a free app tended to report more breastfeeding than peers who did not receive such help, with a more-pronounced effect observed among Black mothers, according to a new RAND study.

Reporting results from the first large trial of telelactation services, researchers found that mothers who were given access to video telelactation services reported slightly higher rates of breastfeeding six months after giving birth, as compared to mothers who did not receive the service.

The ...

Homicide rates across county, race, ethnicity, age, and sex in the US

2025-02-27

About The Study: In this cross-sectional study of U.S. homicide rates, substantial variation was found across and within county, race and ethnicity, sex, and age groups; American Indian and Alaska Native and Black males ages 15 to 44 had the highest rates of homicide. The findings highlight several populations and places where homicide rates were high, but awareness and violence prevention remains limited.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Paula D. Strassle, PhD, MSPH, email pdstrass@umd.edu.

To access the embargoed ...

Prevalence and control of diabetes among US adults

2025-02-27

About The Study: This study found that the prevalence of adults with diabetes did not significantly change between 2013 and 2023, but glycemic control among those with diagnosed disease worsened in 2021-2023 after nearly a decade of stability. This trend was most pronounced among young adults. The increase of 1% in mean HbA1c levels and 20% decrease in glycemic control would increase the lifetime risk of cardiovascular events. Potential explanations for these findings include increased sedentary behavior, reduced social support, heightened mental health ...

Sleep trajectories and all-cause mortality among low-income adults

2025-02-27

About The Study: In this cohort study of 46,000 U.S. residents, nearly two-thirds of participants had suboptimal 5-year sleep duration trajectories. Suboptimal sleep duration trajectories were associated with as much as a 29% increase in risk of all-cause mortality. These findings highlight the importance of maintaining healthy sleep duration over time to reduce mortality risk.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Kelsie M. Full, PhD, MPH, email k.full@vumc.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.62117)

Editor’s ...

The invisible complication: Experts at ACS Summit address surgical adhesions and their hidden costs

2025-02-27

Key Takeaways

Surgical adhesions — internal bands of scar tissue that form between organs or tissues after surgery— can lead to severe complications such as bowel obstructions, chronic pain, and infertility while increasing the difficulty of future operations.

Surgical adhesions negatively impact patient outcomes and drive up health care costs.

There is currently no standard measure of the severity of surgical adhesions or their impact on a patient’s quality of life.

CHICAGO – Scarring is expected after most operations, but surgical adhesions present a unique ...

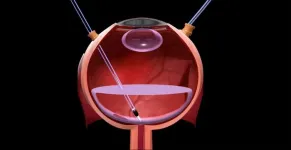

Stem cell transplant clears clinical safety hurdle for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration

2025-02-27

Age-related macular (AMD) degeneration is a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness in the elderly population. In so-called wet AMD, new, abnormal blood vessels grow in the central part of the retina called macula, which is required for high-acuity central vision, leading to fluid and blood leakage and macular damage or dysfunction. Although wet AMD accounts for a minority of AMD cases, 90% of AMD-related cases of blindness are due to wet AMD.

Wet AMD in its early stages can be treated with drugs to reduce the formation of new blood vessels, but this treatment is inefficient in cases where blood vessel formation is already in ...

MSU forges strategic partnership to solve the mystery of how planets are formed

2025-02-27

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Astronomers have long grappled with the question, “How do planets form?” A new collaboration among Michigan State University, Arizona State University and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory will seek to answer this question with the help of a powerful telescope and high-performance computers.

The team of researchers will use 154 hours on the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, to probe the atmospheres of seven planets beyond our solar system – all of which were formed less than 300 million years ago, around the time dinosaurs roamed ...

AAIF2025 conference: International actin conference with comprehensive topics

2025-02-27

Since the discovery of actin in relation to muscle function more than 80 years ago by Albert Szent-Gyorgyi in Szeged, Hungary, actin research has become extremely diverse and now extends to plants and prokaryotes, as well as biochemical, biophysical, molecular, and cellular biology fields. The need for an international actin conference with comprehensive topics, where the latest results and research directions are presented, is critical for the community. Therefore, we decided to bring together the best experts in actin biology from across the world to build research synergies to tackle long-standing questions ...

ASU forges new strategic partnership to solve the mystery of how planets are formed

2025-02-27

Astronomers have long grappled with the question, “How do planets form?” A new collaboration among Arizona State University (ASU) , Michigan State University (MSU) and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) will seek to answer this question with the help of a powerful telescope and high-performance computers.

The team of researchers will use 154 hours on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), to probe the atmospheres of seven planets beyond our solar system – all of which were formed less than 300 million years ago, around the time dinosaurs roamed the Earth. In conjunction with JWST, this collaboration, called the KRONOS program, will use computers ...