(Press-News.org)

Scientists have a new target to prevent cold sores after University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers discovered an unexpected way the herpes virus re-activates in the body. The finding could also have important implications for genital herpes caused by the same virus.

The discovery from UVA’s Anna Cliffe, PhD, and colleagues seems to defy common sense. She and her team found that the slumbering herpes virus will make a protein to trigger the body’s immune response as part of its escape from dormancy. You’d think this would be bad for the virus – that activating the body’s antiviral defenses would be like poking a bear. But, instead, it’s the opposite: The virus highjacks the antiviral process in infected neurons (nerve cells) to make the type of comeback nobody wants.

“Our findings identify the first viral protein required for herpes simplex virus to wake up from dormancy, and, surprisingly, this protein does so by triggering responses that should act against the virus,” said Cliffe of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology. “This is important because it gives us new ways to potentially prevent the virus from waking up and activating immune responses in the nervous system that could have negative consequences in the long term.”

Understanding Herpes Simplex Virus-Associated Disease

Cold sores are caused primarily by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), one of two forms of the herpes virus. HSV-1 is very contagious, and more than 60% of people under 50 have been infected worldwide, the World Health Organization estimates. That’s more than 3.8 billion people.

In addition to causing cold sores, herpes simplex virus 1 can also cause genital herpes, a condition most often associated with HSV-1’s cousin, herpes simplex virus 2. Now, however, there are more new cases of genital herpes in the United States caused by HSV-1 than HSV-2. Notably, the UVA researchers found that herpes simplex virus 2 also makes this same protein and may use a similar mechanism to reactivate. So UVA’s new discovery may also lead to new treatments for genital herpes.

In addition to cold sores and gential herpes, HSV-1 can also cause viral encephalitis (brain infammation) and has been linked to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Once HSV-1 makes its way into our bodies, it stays forever. Our immune systems can send it into hiding, allowing infected people to be symptom free. But stress, other infections and even sunburns are known to cause it to flare. UVA’s new discovery adds another, surprising way it can spring back into action.

The researchers found that while the virus can make a protein called UL12.5 to reactivate, the protein was not needed in the presence of another infection. The scientists believe this is because the infections trigger certain “sensing pathways” that act as the home security system for neurons. Detection of a pathogen alone may be sufficient to trigger the herpes virus to begin replicating, the scientists believe, even in instances of “abortive infections” – when the immune system contains the new pathogen before it can replicate.

“We were surprised to find that HSV-1 doesn’t just passively wait for the right conditions to reactivate – it actively senses danger and takes control of the process,” researcher Patryk Krakowiak said. “Our findings suggest that the virus may be using immune signals as a way to detect cellular stress – whether from neuron damage, infections or other threats – as a cue to escape its host and find a new one.”

With the new understanding of how herpes flares can be triggered, scientists may be able to target the protein to prevent them, the researchers say.

“We are now following up on this work to investigate how the virus is highjacking this response and testing inhibitors of UL12.5 function,” Cliffe said. “Currently, there are no therapies that can prevent the virus from waking up from dormancy, and this stage was thought to only use host proteins. Developing therapies that specifically act on a viral protein is an attractive approach that will likely have fewer side effects than targeting a host protein.”

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research team consisted of Patryk A. Krakowiak, Sean R. Cuddy, Matthew E. Flores, , Abigail L. Whitford, Sara A. Dochnal, Aleksandra Babnis, Tsuyoshi Miyake, Marco Tigano, Daniel A. Engel and Cliffe. The scientists have no financial interest in the work.

The research was supported by National Institute of Health grants R21AI171544, T32AI007046, T32GM008136 and R01AG085782, as well as the Owens Family Foundation, a UVA Global Infectious Disease Institute seed award and UVAWagner Fellowships.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at https://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

Glenview, Illinois – The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), the PF Warriors, the Rare Disease Diversity Coalition (RDDC)—a program at the Black Woman's Health Imperative—and the National Association of Community Health Workers (NACHW) announce their collaboration to address idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) as a chronic disease on Rare Disease Day 2025.

Together, the organizations will employ designated activities that will build a knowledge base on the current IPF landscape ...

The study, which examined 121 babies aged three to twelve months in Accra, the capital of Ghana, demonstrates a remarkable variety of language input in the early months of life. The children are regularly exposed to two to six languages. Strikingly, the number of caregivers the children have also ranges between two and six, and babies who have more adults in their daily lives who regularly take care of them also hear more different languages. In Ghana, families often live in so-called “compound buildings”, where many ...

Virginia Tech is spearheading a research coalition to reveal the untapped potential of the greater Appalachian Mountains region.

This coalition aims to accelerate the identification and characterization of unconventional critical mineral resources throughout the area. It brings together academic institutions, research laboratories, federal and state natural resource offices, and consultancies, all collaborating with the end goal of boosting regional economic growth and creating new jobs.

The research team, led by Richard Bishop, professor of practice in ...

A recent study published in Engineering delves into the behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) under thermocyclic loading. This research, conducted by Ju-Hyung Kim and Yail J. Kim, aims to understand the effects of multi-hazard loading on these strengthened structures, which is crucial for the maintenance and rehabilitation of existing buildings.

Multi-hazards, such as the combination of seismic events and high temperatures, pose ...

Paul Armsworth, Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, has received a 2025 Southeastern Conference Faculty Achievement Award for excellence in teaching, research and service.

He and the 15 other recipients this year — one from each SEC member university — are now nominated for the SEC Professor of the Year Award, which will be announced later in the spring.

“I am thrilled to receive this recognition, but it is also very humbling to be celebrated in this ...

A recent study published in Engineering presents a groundbreaking method for comprehensively evaluating the performance of aeroengines, the crucial components powering aircraft. Authored by Shubin Si and other researchers from esteemed institutions in China, this research addresses long-standing challenges in aeroengine performance assessment.

Aeroengines are complex systems, and their performance directly impacts flight safety and efficiency. Traditional evaluation methods, such as airlines relying on single-parameter indicators like exhaust gas temperature or manufacturers conducting ...

A study led by UMass Chan researchers demonstrated that a gene therapy to correct a mutation that causes maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) prevented newborn death, normalized growth, restored coordinated expression of the affected genes and stabilized biomarkers in a calf as well as in mice.

“Simply put, we believe the gene therapy demonstrated in both animal species, especially in the cow, very well showcases the therapeutic potential for MSUD, in part because the diseased cow, without treatment, has a very similar metabolic profile as the patients,” said Dan Wang, PhD, assistant ...

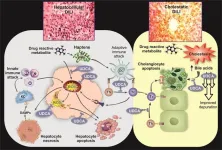

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a significant concern in clinical practice, arising from medications, herbs, and dietary supplements. It can manifest in different forms, including hepatocellular, cholestatic, and mixed types, each associated with specific liver enzyme abnormalities and histological injury patterns. Hepatocellular DILI is characterized by inflammation, necrosis, and apoptosis, while cholestatic DILI involves bile plug formation and bile duct paucity. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a widely used treatment for cholestatic liver diseases, has recently been investigated for its potential therapeutic effects ...

Hepatic biliary adenofibroma (BAF) is a rare benign bile duct neoplasm that has garnered increasing attention due to its potential role as a precursor lesion for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). Although it shares histopathological features with other biliary tumors, BAF is distinct in its composition, consisting of low-grade tubuloglandular and microcystic bile duct structures embedded in a dense fibrous stroma. Despite its classification as a benign tumor, emerging case reports suggest that BAF may undergo malignant transformation. However, its rarity and limited molecular characterization contribute to diagnostic ...

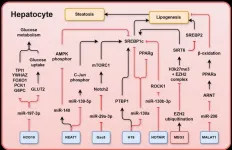

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is a global health challenge, affecting nearly 30% of adults worldwide. A significant subset of MASLD patients progresses to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), liver fibrosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), yet no universally approved treatment exists outside resmetirom. The increasing prevalence of MASLD, driven by obesity and diabetes, highlights an urgent need for innovative therapeutic ...