(Press-News.org) Insect populations, foundational to food chains and pollination, have dramatically declined over the past 20 years due to rapid climate change

Scientists identify two ways fly species from different climates (high-altitude forest and hot desert) have adapted to temperature

Paper provides evidence that changes in brain wiring and heat sensitivity contributed to shifting preference to hot or cold conditions, respectively

Results may help predict the impact of ongoing climate change on insect distribution and behavior

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Tiny, cold-blooded animals like flies depend on their environment to regulate body temperature, making them ideal “canaries in the mine” for gauging the impact of climate change on the behavior and distribution of animal species. Yet, scientists know relatively little about how insect sense and respond to temperature.

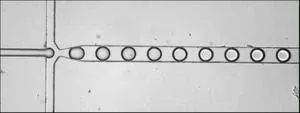

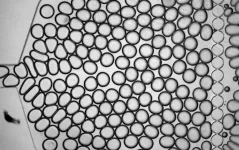

Using two species of flies from different climates — one from the cool, high-altitude forests of Northern California, the other hailing from the hot, dry deserts of the Southwest (both cousins of the common laboratory fly, drosophila melanogaster) — Northwestern scientists discovered remarkable differences in the way each processes external temperature.

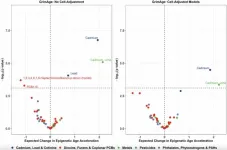

Forest flies showed increased avoidance of heat, potentially explained by higher sensitivity in their antennae’s molecular heat receptors, while desert flies were instead actively attracted to heat, a response that could be tracked to differences in brain wiring in a region of the fly brain that helps compute the valence (inherent attractiveness or aversiveness) of sensory cues.

The scientists believe these two mechanisms may have accompanied the evolution of each species as it adapted to its distinctive thermal environment, starting from a common ancestor dating back 40 million years (not long after dinosaurs went extinct).

These findings, published today (March 5) in the journal Nature, help understand how animals evolve the preferences for specific temperature environments and may help predict the impact of a rapidly changing climate on animal behavior and distribution.

‘Not enough people care about insects’

“Insects are especially threatened by climate change,” said Northwestern neurobiologist Marco Gallio. “Behavior is the first interface between an animal and its environment. Even before the struggle to survive or perish, animals can respond to climate change by migration and by changing their distribution. We are already seeing insect populations declining in many regions, and even insect vectors of disease like the Zika virus and malaria spreading into new areas.”

Gallio, a self-appointed “insect advocate,” is a professor in the neurobiology department and the Soretta and Henry Shapiro Research Professor in Molecular Biology at the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. His lab examines fruit flies and their sensing systems. Gallio acknowledged there is limited data because “not enough people care about the insects,” but that available figures record a dramatic decline in insects in the past 20 to 50 years. Though bug haters may rejoice, Gallio said the population decline in the animal group with the most species on Earth is nothing to celebrate.

In addition to their position at the foundation of most terrestrial food chains, insects pollinate 70% of our crops. Gallio said losing insect communities could cause catastrophic damage to ecosystems across the globe and have a direct impact on human wellbeing.

Understanding heat circuits in the brain

Previous work from the Gallio Lab focused on how small insects like laboratory flies respond to sensory cues like harmless and painful temperature changes.

“The common fruit fly is an especially powerful animal to study how the external world is represented and processed within the brain,” Gallio said. “Many years of work on fly genetics and neuroscience have given us a map of the fly brain more detailed than that of any other animal.”

In the present study, Gallio and colleagues wondered how the brain circuits and resulting behaviors compared in fly species that were very similar aside from their choices of thermal habitat.

Using genetic tools, including CRISPR, to knock out certain genes and gene swaps between species, the team studied both the molecular and brain mechanisms that may explain species-specific differences in temperature preference.

Ph.D. student and lead author Matthew Capek explained that they first found differences in the molecules that detect heat, causing them to activate at different temperatures. And while Capek said the difference in activation could explain the forest flies’ preference for cooler environments, a shift in receptor activation was not enough to explain the behavior of the desert fly.

“The desert fly seemed actively attracted to warmer temperatures — around 90 degrees Fahrenheit compared to the forest fly’s sweet spot just below 70 degrees,” said Capek, who works in the Gallio lab. “In fact, the activation threshold of the antenna heat sensors corresponded to their favorite temperature range, which they will seek, rather than to a temperature they should avoid.”

“In other words, the fly doesn’t behave any longer as though the antennae are telling it to run away from dangerous heat; they seem to be telling it higher temperatures are good, and to approach them.”

High cost, high reward

Gallio was initially puzzled — deserts are hot, so it did not make sense that flies sought out heat — but a lab trip to the Anza Borrego desert of Southern California provided key inspiration.

“Deserts in this region are very hot during the day, but temperatures can drop extremely rapidly when the sun goes down, and night can be downright freezing,” said Alessia Para, also a key author of the study and a research associate professor of neurobiology. “Flies in this climate may need to constantly attend to the rapidly changing temperature and always seek the ideal range, finding shady spots during the day and hiding in cacti for warmth at night.”

Flies from more forgiving environments may instead ignore temperature except when it changes rapidly. Constantly detecting the right temperature is costly from an energy perspective, but for desert flies, it’s life or death.

“This comparative work is useful in a couple of different ways,” Gallio said. “When an animal is born, the brain is already programmed to know if many of the things it will encounter are bad or good for it, and we do not understand how that programming works.

These fly species represent a natural experiment because a stimulus that is good for one species is bad for the other, and we can study the differences that make it so. We also want to learn more about how animals have been able to adapt to different temperatures during evolution, so that we may be able to better understand and even predict how they react to ongoing climate change. Of course we care about the insects, and we hope that what we learn may help us appreciate and protect them better.”

The paper, titled “Evolution of temperature preference behavior in flies of the genus drosophila,” was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants R21NS130554 and 1F31NS129270) and by the PEW Scholars Program. Gallio is a member of the National Science Foundation’s Simons National Institute for Theory and Mathematics in Biology in Chicago.

END

Insect populations are declining — and that is not a good thing

Differences in genes and brain wiring between forest and desert flies could help explain how climate change impacts insects

2025-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover genes to grow bigger tomatoes and eggplants

2025-03-05

Bigger, tastier tomatoes and eggplants could soon grace our dinner plates thanks to Johns Hopkins scientists who have discovered genes that control how large the fruits will grow.

The research—led by teams at Johns Hopkins University and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory—could lead to the development of new varieties of heirloom tomatoes and eggplants, including those that help support agriculture in areas around the world where local varieties are currently too small for large-scale production.

Findings were published in the journal Nature.

“Once ...

Effects of combining coronary calcium score with treatment on plaque progression in familial coronary artery disease

2025-03-05

About The Study: The combination of coronary artery calcium (CAC) score with a primary prevention strategy in intermediate-risk patients with a family history of coronary artery disease was associated with reduction of atherogenic lipids and slower plaque progression compared with usual care. These data support the use of CAC score to assist intensive preventive strategies in intermediate-risk patients.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Thomas H. Marwick, MBBS, PhD, MPH, email Tom.Marwick@bakeridi.edu.au.

To ...

Cancer screening 3 years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

2025-03-05

About The Study: In 2023, reported breast and colorectal cancer screening rebounded from COVID-19 pandemic–related declines and surpassed pre-pandemic estimates. These findings are encouraging given larger-than-expected declines in early-stage breast and colorectal cancer diagnoses in 2020 and increases in distant-stage breast cancer diagnoses through 2021. Cervical cancer screening rates remained below pre-pandemic levels, a troubling trend as early-stage diagnoses continued to decrease in 2021. The persistent decline may in part reflect longer-term declines in patient knowledge and clinician recommendation of cervical cancer ...

Trajectories of sleep duration, sleep onset timing, and continuous glucose monitoring in adults

2025-03-05

About The Study: In this cohort study of middle-aged and older participants, persistent inadequate sleep duration and late sleep onset, whether alone or in combination, were associated with greater glycemic variability. These findings emphasize the importance of considering both sleep duration and timing for optimizing glycemic control in the general population.

Corresponding Authors: To contact the corresponding authors, email Ju-Sheng Zheng, PhD, (zhengjusheng@westlake.edu.cn) and Yu-ming Chen, PhD, (chenyum@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link ...

Sports gambling and drinking behaviors over time

2025-03-05

About The Study: This study found that over time, the trajectory of sports gambling frequency was associated with the trajectory of alcohol-related problems. Screening and treatment interventions are recommended for sport gamblers who also drink concurrently, especially because this group appears to be at an elevated risk for developing greater alcohol-related problems over time.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Joshua B. Grubbs, PhD, email joshuagrubbs12@unm.edu

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0024)

Editor’s Note: Please ...

For better quantum sensing, go with the flow

2025-03-05

Combine a garden-variety green laser, microwaves with roughly the energy of your wi-fi, and some diamond dust in drops of water, and what do you get? A precise chemical detection tool.

For the first time, researchers have combined nanodiamonds in microdroplets of liquid for quantum sensing. The new technique is precise, fast, sensitive, and requires only small amounts of the material to be studied – helpful when studying trace chemicals or individual cells. The results were published in the journal Science Advances in December.

“We weren’t even sure ...

Toxic environmental pollutants linked to faster aging and health risks in US adults

2025-03-05

“Environmental chemical exposures represent a key modifiable risk factor impacting human health and longevity, and our findings provide evidence for associations between several environmental exposures and epigenetic aging in a large sample representative of the US adult population.”

BUFFALO, NY — March 5, 2025 — A new research paper was published in Aging (Aging-US) on February 11, 2025, Volume 17, Issue 2, titled “Exposome-wide association study of environmental chemical exposures ...

Jerome Morris voted AERA President-Elect; key members elected to AERA Council

2025-03-05

Jerome E. Morris, the E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor of Urban Education at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, has been voted president-elect of the American Educational Research Association (AERA). Morris joins the AERA Council in 2025–2026 as president-elect, and his presidency begins at the conclusion of the association’s 2026 Annual Meeting.

Morris leverages his upbringing in public housing and attending predominantly Black public schools in Birmingham, Alabama, to inform his research, which examines the intersection of ...

Study reveals how agave plants survive extreme droughts

2025-03-05

WASHINGTON — Agave plants may be best known for their role in tequila production, but they are also remarkably adept at retaining water in extremely dry environments. In a new study, researchers used terahertz spectroscopy and imaging to gain new insights into how these succulents store and manage water to survive in dry conditions.

“Understanding how plants adapt to dry conditions could lead to better farming practices and be used to develop crops that require less water,” said Monica Ortiz-Martinez ...

Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) launches a second funding opportunity to accelerate novel tool development to advance Parkinson's disease research

2025-03-05

The Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative opened applications for research community members to apply for funding to develop novel tools to advance Parkinson’s disease (PD) research. The Collaborative Research Network (CRN) 2025 Technical Track grants will support the development of sustainable tools to accelerate validation and therapeutic research and discovery for emerging targets identified through ASAP discoveries, offering funding of up to $2M per year over three years, up to $6M total.

"By bringing researchers together to generate new preclinical tools for targets studied in our ASAP programs, our goal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

[Press-News.org] Insect populations are declining — and that is not a good thingDifferences in genes and brain wiring between forest and desert flies could help explain how climate change impacts insects