(Press-News.org) OKLAHOMA CITY – Polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a family of genetic disorders that causes clusters of cysts to form on the kidney, is among the most common genetic disorders, affecting some 500,000 people in the United States. Roughly one in every 1,000 people will develop some form of cystic kidney disease during their lifetime, and nearly 40,000 Oklahomans have a chronic kidney disease, according to the Oklahoma Health Care Authority.

For many patients, dialysis – a time-consuming and costly procedure – is one of few treatment options. A 2021 study by researchers at Tufts University found that the average annual cost of dialysis for patients in the United States is about $40,000.

Now, new research from the University of Oklahoma aims to unravel the genetic mysteries of this disease and, in the process, open the door to novel therapies.

Researchers have long understood that PKD is associated with kidney cysts and fibrosis and a gradual decline in renal function – a measure of the kidney’s ability to remove waste and fluid from the body. A key unresolved question is what drives the renal function drop-off.

“When people have mutations in certain genes, they can end up with kidney cysts, which alter the tubular architecture of the organ,” said Leonidas Tsiokas, Ph.D., a professor of cell biology at the OU College of Medicine and lead investigator for the study. “What we don’t know is exactly how you go from a normal kidney to a cystic one.”

Since late 2024, Tsiokas and colleagues at OU Health Sciences have begun research funded through a four-year, $2 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. A key focus of the study is to identify genes and associated proteins responsible for PKD and their contribution to renal function.

“We know of about 40 genes that play a role in polycystic kidney disease. But these genes have yet to explain the trigger of how you can go from a normal tubule to an elongated tubule to a tubule where the diameter is affected and not functioning,” he said.

“In other words, we know the result of mutated genes, but we don’t know the cellular process by which this disease develops.”

To address these questions, Tsiokas and Maulin Patel, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow in Tsiokas' lab, are zeroing in on Fbxw7, a gene known to play an important role in basic cellular functions that could be linked to cystogenesis, fibrosis, and cellular death and degeneration. Its role in PKD had never been examined before.

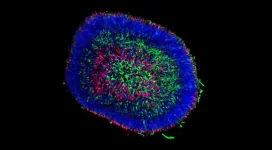

Tsiokas speculated that by genetically deleting Fbxw7 in a mouse model used to study kidney function, he could re-create the process of cystogenesis in mice. Preliminary data suggest he’s correct.

“When Fbxw7 is deleted, we found that (those) mice develop slowly progressing cystic kidney disease without kidney enlargement, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, tubular degeneration, and a progressive decline in kidney function,” Tsiokas said. Importantly, the changes observed are cardinal features of several types of PKD, including nephronophthisis (NPHP), a genetic kidney disorder that affects children. One in 50,000 children worldwide suffers from nephronophthisis.

Further study of the mice with the Fbxw7 gene deletion revealed that renal function declines were connected to an abnormal accumulation of a protein called SOX9. Normalizing its levels by genetically deleting just one copy of the SOX9 gene restored overall renal function, Tsiokas said.

Tsiokas said these findings offer the first conclusive evidence of the genes that directly modulate fibrocystic diseases of the kidney and are an essential step in efforts to identify “druggable targets” for genetic forms of cystic kidney disorders. Future work will seek to catalog how cystogenesis develops, how it is modulated by fibrosis or tubular degeneration, and how these processes interact to impact renal function.

“Understanding these processes will give us fresh ideas of how to delve further into the mechanisms of the pathogenesis of cystic kidney disease and how we might treat it,” he said.

###

About the Project

The research is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, award No. R01DK138339.

END

OKLAHOMA CITY – When mothers eat a diet high in fat and sugars, their unborn babies can develop liver stress that continues into early life. A new study published in the journal Liver International sheds light on changes to the fetus’s bile acid, which affects how liver disease develops and progresses.

Bile acids typically help with digestion and absorb dietary fats in the small intestine, but when they reach excessive levels, they become toxic and can damage the liver. While the mother can detoxify the acids, the fetus lacks that ability. Bile acids may re-circulate to the mother for detoxification, but if they don’t, they build ...

More than 3 billion years ago, Mars intermittently had liquid water on its surface. After the planet lost much of its atmosphere, however, surface water could no longer persist. The fate of Mars’ water—whether it was buried as ice, confined in deep aquifers, incorporated into minerals or dissipated into space—remains an area of ongoing research, one of particular interest to LASP Senior Research Scientist Bruce Jakosky, former principal investigator of the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) mission.

Last week, in a letter to the editor ...

MADISON — Inside the human eye, the retina is made up of several types of cells, including the light-sensing photoreceptors that initiate the cascade of events that lead to vision. Damage to the photoreceptors, either through degenerative disease or injury, leads to permanent vision impairment or blindness.

David Gamm, director of UW–Madison’s McPherson Eye Research Institute and professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, says that stem cell replacement therapy using lab-grown photoreceptors ...

High-grade glioma, an aggressive form of pediatric and adult brain cancer, is challenging to treat given the tumor location, incidence of recurrence and difficulty for drugs to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Researchers from the University of Michigan, Dana Farber Cancer Institute and the Medical University of Vienna established a collaborative team to uncover a potential new avenue to address this disease.

A study, published in Cancer Cell, shows that high-grade glioma tumor cells harboring DNA alterations in the gene PDGFRA responded to the drug avapritinib, which is already approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to treat gastrointestinal ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), in partnership with NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), has developed StarBurst, a small satellite (SmallSat) instrument for NASA's StarBurst Multimessenger Pioneer mission, which will detect the emission of short gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), a key electromagnetic (EM) signature that will contribute to the understanding of neutron star (NS) mergers.

NRL transferred the instrument to NASA on March 4 for the next phase, environmental ...

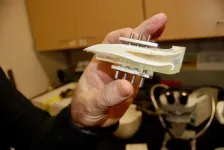

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – March 13, 2025 – A study from researchers at Wake Forest University School of Medicine highlights a new approach in addressing conductive hearing loss. A team of scientists, led by Mohammad J. Moghimi, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical engineering, designed a new type of hearing aid that not only improves hearing but also offers a safe, non-invasive alternative to implantable devices and corrective surgeries.

The study recently published in Communications Engineering, a Nature Portfolio journal.

Conductive ...

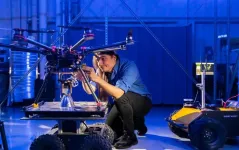

Envision a world where unmanned aircraft deliver goods to your front door and transport passengers in flying taxis, cargo planes cross continents carrying vital trade goods, and fighter jets patrol battle zones—all without a human pilot at the controls.

Those scenarios might seem a bit far-fetched now, but researchers are working diligently to develop these aircraft and ensure they operate safely. That’s why NASA has awarded a $1 million grant through its University Leadership Initiative (ULI) to a team from The University of Texas at Arlington Research ...

You may scarcely notice it, but much of what you do every day requires your brain to engage in perceptual learning. To safely cross an intersection or quickly retrieve something from your bag, you depend upon your brain to first assign meaning to sensory input from your eyes or fingertips.

Usually, it’s effortless.

Research from The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology shows a gene called Syngap1 enables touch-based perception, while certain mutations can lead to mixed signals. The research was made possible through grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute ...

Teeth recovered from a beloved zoo elephant that died in 2008 are helping University of Utah geologists develop a method for tracking the movements of large herbivores across landscapes, even for animals now extinct, such as mastodons and mammoths.

Outlined in recently published findings, the technique analyzes isotope ratios of the element strontium (Sr), which accumulates in tooth enamel. For large plant-eating land mammals, the relative abundance of two strontium isotopes in teeth and tusks ...

For cancers of organs like the liver, the long-term impact of our diet has been well studied — so much so that we have guidance about red meat, wine and other delicacies.

A new study from researchers at University of Florida Health looks at another kind of organ whose cancer risk may be affected by poor diet: the lungs. The study was funded by several National Institutes of Health grants and a collaboration between the University of Kentucky's Markey Cancer Center and the UF Health Cancer Center.

“Lung ...