(Press-News.org) As animals experience new things, the connections between neurons, called synapses, strengthen or weaken in response to events and the activity they cause in the brain. Neuroscientists believe that synaptic plasticity, as these changes are called, plays an important role in storing memories.

However, the rules governing when and how much synapses change are not well understood. The traditional view is that the more two neurons fire together, the stronger their connection becomes; when they fire separately, their connection weakens.

New research from the University of Chicago on the hippocampus, a brain area essential for memory, suggests that this is not the whole story. Other rules of synaptic plasticity appear to have a bigger effect and better explain how brain activity continually reshapes the way memories are recorded in the brain.

Patterns of activity and their neuronal representations change a lot as an animal becomes more familiar with a new environment or experience. Surprisingly, those patterns keep evolving even once something is learned, albeit more slowly.

“When you go into a room, it’s new at first but it quickly becomes familiar to you every time you come back,” said Mark Sheffield, PhD, Associate Professor of Neurobiology and the Neuroscience Institute at UChicago and senior author of the new study published in Nature Neuroscience. “So, you might expect that neuronal activity representing that room would settle and become stable, but it continues to change.

“These changes in representation, during learning and after, must be driven by synaptic plasticity, but what kind of plasticity exactly? It’s hard to know, because we don’t have the technology to measure that directly in behaving animals,” he said.

Shifting place cells

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded for the discovery of “place cells”: neurons in the hippocampus that activate only when an animal is at a certain spot in a room, called the “place field.” Different neurons have their place fields at different locations in the room, covering the entire environment and forming what’s known as a cognitive map.

In the new study, Antoine Madar, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Sheffield’s lab, studied place cell activity recorded in the brains of mice as they scampered through different environments. The mice first ran through a familiar environment, then switched to an unfamiliar one. The researchers expected to see the same patterns of activity when the mice were in a place they knew, and different patterns as they learned a new environment. Instead, they saw that the activity was slightly different every time, and reasoned that these changes reflected synaptic plasticity.

To understand what drives these constant changes in neuronal representations, Madar built a computational model of hippocampal neurons, and then applied different plasticity rules to see if they would make place cells behave in the same patterns seen in the mouse data. Instead of the traditional “neurons that fire together wire together” rule, known as Hebbian Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP), a different, non-Hebbian rule called Behavioral Timescale Synaptic Plasticity (BTSP) best explained the shifting place field dynamics.

Some changes in place cell activity were subtle; the cell fired in a slightly different location than the previous time. Others were more drastic, jumping to a completely different location. STDP could only explain the small gradual shifts, Madar said, but BTSP could explain the whole range of shifting trajectories, including the big nonlinear shifts.

“We know a lot about the physiology that supports synaptic plasticity, but we usually don't know how important those things are for learning,” Madar said. “Our study provides evidence that BTSP is more impactful than STDP in shaping hippocampal activity during familiarization.”

BTSP is a fairly recent discovery, so Madar said that comparing their data and models allowed them to learn a lot about this new plasticity rule. For instance, they knew that BSTP is triggered by large jumps in the amount of calcium inside cells, but they didn’t know how frequently these jumps happen. The new research shows that while these jumps are rare, they occur more frequently when an animal is learning and forming new memories. The researchers also found that once a place field forms, the probability of these BTSP-triggering events follows a simple decaying pattern, with only slight variations across brain regions or familiarity levels.

“This is enough to explain the awesome diversity in individual place field dynamics that we observed,” Madar said.

Encoding the entire experience

Although the research shows that hippocampal activity is much more dynamic during memory formation than previously thought, it’s still not clear what purpose these shifting representations could serve.

“Continually evolving neuronal representations could help the brain distinguish between similar memories that happened in the same place but at different times, a very important process to avoid pathological memory confusion, a hallmark of multiple neurological and cognitive disorders,” Madar said.

Sheffield starts to sound Proustian when considering this question.

“Every time you come back into the room that you're sitting in, you're somehow able to track that you're in the same room. But it's a different day and a different time, right? You can never completely replicate an experience, and somehow the brain tracks all that,” he said.

“So, one idea is that these dynamics in memory representations are encoding just that. They're encoding slight changes in the experience, like maybe you have a coffee one time and later you have lunch in the same room. These subtle differences in setting, odors, time — all these slight changes in experience could be encoded into the memory through the changes in these place fields. They're not just encoding the environment; they're encoding the entire experience that occurs there.”

The study, “Synaptic Plasticity Rules Driving Representational Shifting in the Hippocampus,” was funded by the National Institutes of Health (DP2NS111657, F32MH126643), the Whitehall Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program and the Sloan Foundation. Anqi Jiang and Can Dong, current and former PhD students at UChicago, were additional authors.

END

New rules for the game of memory

New research from UChicago upends traditional views on how synaptic plasticity supports memory and learning.

2025-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A simple way to control superconductivity

2025-03-20

Scientists from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science (CEMS) and collaborators have discovered a groundbreaking way to control superconductivity—an essential phenomenon for developing more energy-efficient technologies and quantum computing—by simply twisting atomically thin layers within a layered device. By adjusting the twist angle, they were able to finely tune the “superconducting gap,” which plays a key role in the behavior of these materials. The research was published in Nature Physics.

The superconducting gap is the energy threshold required to break apart Cooper pairs—bound electron pairs that enable superconductivity at low temperatures. ...

New CRISPR tool enables more seamless gene editing — and improved disease modeling

2025-03-20

New Haven, Conn. — Advances in the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR-Cas9 over the past 15 years have yielded important new insights into the roles that specific genes play in many diseases. But to date this technology — which allows scientists to use a “guide” RNA to modify DNA sequences and evaluate the effects — is able to target, delete, replace, or modify only single gene sequences with a single guide RNA and has limited ability to assess multiple genetic changes simultaneously.

Now, however, Yale scientists have developed a series of sophisticated mouse models using CRISPR (“clustered regularly ...

AI technology for colon cancer detection shows promise for widespread use – in the future

2025-03-20

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) released a new clinical guideline making no recommendation — for or against — the use of computer-aided detection systems (CADe) in colonoscopy. A rigorous review of evidence showed that artificial intelligence-assisted technology helps identify colorectal polyps. However, its impact on preventing colorectal cancer — the third most common cancer worldwide — remains unclear.

Colonoscopy, performed more than 15 million times annually in the U.S., is an effective tool for detecting and preventing colorectal cancer. CADe systems have been shown to improve polyp detection ...

Researchers identify promising drug candidates for previously “undruggable” cancer target

2025-03-20

For the first time scientists have identified promising drug candidates that bind irreversibly with a notoriously “undruggable” cancer protein target, permanently blocking it.

Transcription factors are proteins that act as ‘master switches’ of gene activity and play a key role in cancer development. Attempts over the years to design “small molecule” drugs that block them have been largely unsuccessful, so in recent years scientists have explored using peptides – small protein fragments – to block these “undruggable” targets.

Now researchers from the University of Bath have for ...

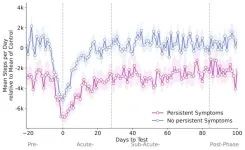

Smartwatch data: Study finds early health differences in long COVID patients

2025-03-20

[Vienna, 19.03.2025]—Between April 2020 and December 2022, over 535,000 people in Germany downloaded and activated the Corona Data Donation App (CDA). Of these, more than 120,000 voluntarily shared daily data from their smartwatches and fitness trackers with researchers, providing insights into vital functions such as resting heart rate and step count.

“These high-resolution data served as the starting point for our study,” explains CSH researcher Katharina Ledebur. “We were able to compare vital signs in 15-minute intervals before, during, and after a SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Higher Resting Heart Rate ...

Mere whiff of penguin poo pushes krill to take frantic evasive action

2025-03-20

Imagine looking at the world through the stalked compound eyes of krill in the Southern Ocean. All of a sudden, a penguin appears like a voracious giant, streamlined like a torpedo, chasing and consuming thousands of krill at rapid speed.

Now, researchers have shown that the water-borne smell of the poo of these flightless birds is enough to cause the krill to show escape behaviors.

“Here we show for the first time that a small amount of penguin guano causes a sudden change in the feeding and swimming behaviors of Antarctic krill,” said Dr Nicole ...

Deep in the Mediterranean, in search of quantum gravity

2025-03-20

Quantum gravity is the missing link between general relativity and quantum mechanics, the yet-to-be-discovered key to a unified theory capable of explaining both the infinitely large and the infinitely small. The solution to this puzzle might lie in the humble neutrino, an elementary particle with no electric charge and almost invisible, as it rarely interacts with matter, passing through everything on our planet without consequences.

For this very reason, neutrinos are difficult to detect. However, in rare cases, ...

Parts of the brain that are needed to remember words identified

2025-03-20

The parts of the brain that are needed to remember words, and how these are affected by a common form of epilepsy, have been identified by a team of neurologists and neurosurgeons at UCL.

The new study, published in Brain Communications, found that shrinkage in the front and side of the brain (prefrontal, temporal and cingulate cortices, and the hippocampus) was linked to difficulty remembering words.

The new discovery highlights how the network that is involved in creating and storing word memories is dispersed throughout the brain.

This is particularly crucial for helping to understand conditions such as epilepsy, in which patients may have difficulty with remembering words. ...

Anti-amyloid drug shows signs of preventing Alzheimer’s dementia

2025-03-20

An experimental drug appears to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s-related dementia in people destined to develop the disease in their 30s, 40s or 50s, according to the results of a study led by the Knight Family Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network-Trials Unit (DIAN-TU), which is based at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The findings suggest – for the first time in a clinical trial – that early treatment to remove amyloid plaques from the brain many years before symptoms arise can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s dementia.

The study is published March 19 in The Lancet Neurology.

The international study ...

Sharing mealtimes with others linked to better wellbeing

2025-03-20

UCL Press Release

Under embargo until Thursday 20th March, 00:01 UK time / Wednesday 19th March, 20:01 Eastern US time

Not peer reviewed | Literature review & data analysis | People

People who share more mealtimes with others are more likely to report higher levels of life satisfaction and wellbeing, finds research led by a UCL academic for the World Happiness Report.

In chapter three of the report, Sharing Meals with Others, the researchers from UCL, University of Oxford, Harvard University and Gallup found that meal sharing as an indicator ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] New rules for the game of memoryNew research from UChicago upends traditional views on how synaptic plasticity supports memory and learning.