(Press-News.org) Challenging long-held assumptions about global terrestrial carbon storage, a new study finds that the majority of carbon dioxide (CO2) absorbed by ecosystems has been locked away in dead plant material, soils, and sediments, rather than living biomass, researchers report. These new insights, which suggest that terrestrial carbon stocks are more resilient and stable than previously appreciated, are crucial for shaping future climate mitigation strategies and optimizing carbon sequestration efforts. Recent studies have shown that terrestrial carbon stocks are increasing, offsetting ~30% of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. A primary mechanism driving this trend is the CO2 fertilization effect, in which elevated atmospheric CO2 levels enhance plant productivity. However, it is uncertain how much organic carbon is stored in living biomass versus nonliving organic reservoirs, such as plant detritus, soils, and sediments. Understanding this distribution is crucial because different pools have varying carbon residence times and vulnerabilities to environmental change. Nevertheless, accurately quantifying living and nonliving carbon storage pools has proven difficult. To address this challenge, Yinon Bar-On and colleagues developed a comprehensive assessment of global changes in woody vegetation carbon stocks by harmonizing diverse remote-sensing estimates with upscaled field inventory data from 1992 to 2019. This integrated approach allowed the authors to partition terrestrial carbon accumulation between living biomass and nonliving organic reservoirs providing a more complete understanding of carbon distribution across ecosystems. Bar-On et al. discovered that while terrestrial ecosystems accumulated approximately 35 ± 14 gigatons of carbon (GtC) during the study period, global living biomass stocks increased by only about 1 ± 7 GtC. The findings indicate that most of the carbon sequestered over the last 3 decades was stored as nonliving organic matter in soils, deadwood, and human-influenced reservoirs like dams and landfills. These pools persist far longer than living biomass, suggesting that terrestrial carbon storage may be more stable over time than previously assumed. “Although the study of Bar-On et al. primarily focused on woody biomass because of its large carbon stocks, the role of grass-dominated ecosystems, where soil carbon sequestration is the dominant storage mechanism, merits further investigation,” writes Josep Canadell in a related Perspective. “A more regional and ecosystem-based analysis will further provide key insights to enable the design of strategies for the conservation of carbon stocks and enhancement of CO2 sinks for climate mitigation.”

END

Majority of carbon sequestered on land is locked in nonliving carbon reservoirs

Summary author: Walter Beckwith

2025-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

From dinosaurs to birds: the origins of feather formation

2025-03-20

Feathers are among the most complex cutaneous appendages in the animal kingdom. While their evolutionary origin has been widely debated, paleontological discoveries and developmental biology studies suggest that feathers evolved from simple structures known as proto-feathers. These primitive structures, composed of a single tubular filament, emerged around 200 million years ago in certain dinosaurs. Paleontologists continue to discuss the possibility of their even earlier presence in the common ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs (the first flying vertebrates with membranous wings) around 240 million years ago.

Proto-feathers are ...

Why don’t we remember being a baby? New study provides clues

2025-03-20

Though we learn so much during our first years of life, we can’t, as adults, remember specific events from that time. Researchers have long believed we don’t hold onto these experiences because the part of the brain responsible for saving memories — the hippocampus — is still developing well into adolescence and just can’t encode memories in our earliest years. But new Yale research finds evidence that’s not the case.

In a study, Yale researchers showed infants ...

The cell’s powerhouses: Molecular machines enable efficient energy production

2025-03-20

Mitochondria are the powerhouses in our cells, producing the energy for all vital processes. Using cryo-electron tomography, researchers at the University of Basel, Switzerland, have now gained insight into the architecture of mitochondria at unprecedented resolution. They discovered that the proteins responsible for energy generation assemble into large “supercomplexes”, which play a crucial role in providing the cell’s energy.

Most living organisms on our planet-whether plants, animals, or ...

Most of the carbon sequestered on land is stored in soil and water

2025-03-20

Recent studies have shown that carbon stocks in terrestrial ecosystems are increasing, mitigating around 30% of the CO2 emissions linked to human activities. The overall value of carbon sinks on the earth's surface is fairly well known—as it can be deduced from the planet's total carbon balance anthropogenic emissions, the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere and the ocean sinks—yet, researchers know very little about carbon distribution between the various terrestrial pools: living vegetation—mainly forests—and nonliving carbon pools—soil organic matter, sediments at the bottom of lakes and rivers, wetlands, ...

New US Academic Alliance for the IPCC opens critical nomination access

2025-03-20

WASHINGTON — The American Geophysical Union and the U.S. Academic Alliance for the IPCC today open calls for U.S. researchers to self-nominate as experts, authors and review editors for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Seventh Assessment Report through a new application portal. The IPCC nomination period opened in early March and will close in mid-April.

USAA-IPCC is a newly established network of U.S. academic institutions registered as observers with the IPCC. Both observer organizations and governments may nominate experts for ...

Breakthrough molecular movie reveals DNA’s unzipping mechanism with implications for viral and cancer treatments

2025-03-20

Scientists at the University of Leicester have captured the first detailed “molecular movie” showing DNA being unzipped at the atomic level – revealing how cells begin the crucial process of copying their genetic material.

The groundbreaking discovery, published in the prestigious journal Nature, could have far-reaching implications, helping us to understand how certain viruses and cancers replicate.

Using cutting edge cryo-electron microscopy, the team of scientists were able to visualise a helicase enzyme (nature’s DNA unzipping machine) in the process of unwinding DNA. DNA helicases are essential during DNA replication because ...

New function discovered for protein important in leukemia

2025-03-20

The protein (Exportin-1) is often found in high levels in patients with leukemia, other cancers

Protein was previously known to move materials out of a cell’s nucleus

New findings suggest protein may also stimulate transcription, which if hijacked, could contribute to abnormal cell division (cancer)

Future anti-cancer therapies that target Exportin-1’s role in transcription may be less toxic or more effective than current therapies

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Researchers from Northwestern University have stumbled upon a previously unobserved function of a protein found in the cell nuclei of all flora and fauna. In addition to exporting ...

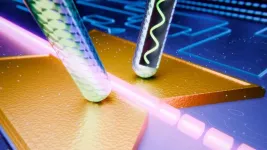

Tiny component for record-breaking bandwidth

2025-03-20

Plasmonic modulators are tiny components that convert electrical signals into optical signals in order to transport them through optical fibres. A modulator of this kind had never managed to transmit data with a frequency of over a terahertz (over a trillion oscillations per second). Now, researchers from the group led by Jürg Leuthold, Professor of Photonics and Communications at ETH Zurich, have succeeded in doing just that. Previous modulators could only convert frequencies up to 100 or 200 gigahertz ...

In police recruitment efforts, humanizing officers can boost interest

2025-03-20

Many U.S. police departments face a serious recruiting and staffing crisis, which has spurred a re-examination of recruitment methods. In a new study, researchers drew on the field of intergroup communication to analyze how police are portrayed in recruitment materials to determine whether humanizing efforts make a difference. The study found that presenting officers in human terms boosted participants’ interest in policing as a career.

The study was conducted by researchers at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), Texas State University (TXST), ...

Fully AI driven weather prediction system could start revolution in forecasting

2025-03-20

A new AI weather prediction system, Aardvark Weather, can deliver accurate forecasts tens of times faster and using thousands of times less computing power than current AI and physics-based forecasting systems, according to research published today (Thursday 20 March) in Nature.

Aardvark has been developed by researchers from the University of Cambridge supported by the Alan Turing Institute, Microsoft Research and the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, providing a blueprint for a completely new approach to weather forecasting with the potential to transform current practices.

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

[Press-News.org] Majority of carbon sequestered on land is locked in nonliving carbon reservoirsSummary author: Walter Beckwith