The researchers will present their results at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2025 is being held March 23-27; it features about 12,000 presentations on a range of science topics.

As it turns out, the chemistry in South Dakota’s Wind Cave is likely similar to places like Europa — and easier to reach. This is why astrobiologist Joshua Sebree, a professor at the University of Northern Iowa, ended up hundreds of feet underground investigating the minerals and lifeforms in these dark, cold conditions.

“The purpose of this project as a whole is to try to better understand the chemistry taking place underground that’s telling us about how life can be supported,” he explains.

As Sebree and his students began to venture into new areas of Wind Cave and other caves across the U.S., they mapped the rock formations, passages, streams and organisms they found. As they explored, they brought along their black lights (UV lights), too, to look at the minerals in the rocks.

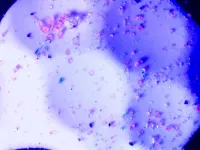

Under the black light, certain areas of the caves seemed to transform into something otherworldly as portions of the surrounding rocks shone in different hues. Thanks to impurities lodged within the Earth millions of years ago — chemistry fossils, almost — the hues corresponded with different concentrations and types of organic or inorganic compounds. These shining stones often indicated where water once carried minerals down from the surface.

“The walls just looked completely blank and devoid of anything interesting,” says Sebree. “But then, when we turned on the black lights, what used to be just a plain brown wall turned into a bright layer of fluorescent mineral that indicated where a pool of water used to be 10,000 or 20,000 years ago.”

Typically, to understand the chemical makeup of a cave feature, a rock sample is removed and taken back to the lab. But Sebree and his team collect the fluorescence spectra — which is like a fingerprint of the chemical makeup — of different surfaces using a portable spectrometer while on their expeditions. That way, they can take the information with them but leave the cave behind and intact.

Anna Van Der Weide, an undergraduate student at the university, has accompanied Sebree on some of these explorations. Using the information collected during that fieldwork, she is building a publicly accessible inventory of fluorescence fingerprints to help provide an additional layer of information to the traditional cave map and paint a more complete picture of its history and formation.

Additional undergraduate students have contributed to the study. Jacqueline Heggen is further exploring these caves as a simulated environment for astrobiological extremophiles; Jordan Holloway is developing an autonomous spectrometer to make measurement easier and even possible for future extraterrestrial missions; and Celia Langemo is studying biometrics to keep explorers of extreme environments safe. These three students are also presenting their findings at ACS Spring 2025.

Doing science in a cave is not without its challenges. For example, in the 48-degrees Fahrenheit (9-degrees Celsius) temperature of Minnesota’s Mystery Cave, the team had to bury the spectrometer’s batteries in handwarmers to keep them from dying. Other times, to reach an area of interest, the scientists had to squeeze through spaces less than a foot (30 centimeters) wide for hundreds of feet, sometimes losing a shoe (or pants) in the process. Or, they’d have to stand knee-deep in freezing cave water to take a measurement, and hope that their instruments didn’t go for an accidental swim.

But despite these hurdles, the caves have revealed a wealth of information already. In Wind Cave, the team found that manganese-rich waters had carved out the cave and produced the striped zebra calcites within, which glowed pink under black light. The calcites grew underground, fed by the manganese-rich water. Sebree believes that when these rocks shattered, since calcite is weaker than the limestone also comprising the cave, the calcite worked to expand the cave too. “It’s a very different cave forming mechanism than has previously been looked at before,” he says.

And the unique research conditions have provided a memorable experience to Van Der Weide. “It was really cool to see how you can apply science out in the field and to learn how you function in those environments,” she concludes.

In the future, Sebree hopes to further confirm the accuracy of the fluorescence technique by comparing it to traditional, destructive techniques. He also wants to investigate the cave water that also fluoresces to understand how life on Earth’s surface has affected life deep underground and, reconnecting to his astrobiological roots, understand how similar, mineral-rich water may support life in the far reaches of our solar system.

The research was funded by NASA and the Iowa Space Grant Consortium.

A Headline Science YouTube Short about this topic will be posted on Tuesday, March 25. Reporters can access the video during the embargo period, and once the embargo is lifted the same URL will allow the public to access the content. Visit the ACS Spring 2025 program to learn more about these presentations, “Developing a cave science spectral database for fluorescence inventory,” “Spectroscopic analysis of caves: The influence of organic overburden on karst speleothems” and other science presentations.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1876 and chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS is committed to improving all lives through the transforming power of chemistry. Its mission is to advance scientific knowledge, empower a global community and champion scientific integrity, and its vision is a world built on science. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, e-books and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Registered journalists can subscribe to the ACS journalist news portal on EurekAlert! to access embargoed and public science press releases. For media inquiries, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society. ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Follow us: Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Title

Developing a cave science spectral database for fluorescence inventory

Abstract

A resource inventory in cave studies is a systematic approach to cataloging and analyzing the natural features found within a cave. This process involves identifying and documenting speleothems (like stalactites, stalagmites, and flowstones) to understand their composition, formation, and historical development. By examining these features, researchers can gain insights into the cave’s geological history and compare it with other caves.

A method we have developed in a resource inventory is the fluorescence inventory, which involves analyzing the unique fluorescence fingerprints of speleothems. When exposed to UV light, these features exhibit distinct fluorescent patterns that reveal hidden details, such as flowstone bands obscured by dust. The UV light reveals more features of the cave that were previously hidden due to surface dust covering them. The light is able to look behind the surface and illuminate features obscure to the eye in white light. The additional hidden features that are able to be added to the cave inventory provide more pieces to the puzzle of the cave and its formation. Using UV light with a filter and a spectrometer, fluorescent patterns are captured and photographed to determine the composition and to compare spectra within the cave and across different caves.

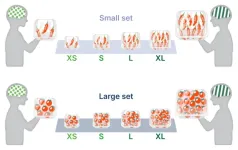

To document and analyze the data effectively, a survey and mapping system has been developed. If a cave map is available, fluorescent features are noted relative to existing survey markers. If not, a survey and sketch of the cave passage are made. Data from the spectrometer, the three spectra per location, are graphed and averaged to reduce random errors and provide a clearer "fingerprint" of the speleothems. This information is compiled into a spreadsheet with details on cave locations, survey markers, fluorescence data, and additional notes, facilitating a thorough analysis of the cave's resources.

The mapping system also allows for an efficient overlay of fluorescent findings onto existing cave maps. If a map already exists, the fluorescent data can be easily integrated, marking new features that were previously undetected by traditional methods. In caves where no maps exist, a survey is taken, and the fluorescent data can then be layered onto these maps. This dual capability enhances the overall resource inventory by not only documenting visible features but also illuminating hidden ones, creating a more comprehensive and multi-layered understanding of the cave environment.

Title

Spectroscopic analysis of caves: The influence of organic overburden on karst speleothems

Abstract

In order to understand the pathways by which life could be sustained within the Solar System, extreme environments on Earth must first be examined. Within the Solar System, the icy moons of Europa and Enceladus harbor organics within interstitial lakes which may be able to sustain life. Titan’s liquid methane cycle may create caves that are karstic in nature, carved in the organically rich dunes of the surface. To determine the availability of resources on other planets, terrestrial comparisons must be available to characterize components trapped within foreign materials.

Terrestrial caves present an opportunity to examine the flow of organics in an environment that is mostly isolated from external realms yet remains within human reach. As water passes through the overburdened material, decomposed plant materials and other organics are drawn into the water. Organically laced water can further create calcite features, such as flowstone, that store a record of organics from the surface. When exposed to ultraviolet light, the organically laced water and speleothems fluoresce. Utilizing noninvasive in-situ techniques, a portable spectrometer can be used to examine the unique color fingerprint of flowstone when exposed to ultraviolet light. Cave water has been collected and further examined to understand the fluorescence within the water itself. By freezing cave water with liquid nitrogen, cryogenic ice features, similar to what may be on Europa or Enceladus can be created and studied, providing clues into the behaviors of organics on the icy moons of the Solar System. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry can be used to determine molecules that contribute to speleothem’s fluorescence nature.

Surface conditions of karst environments can alter the fluorescence of water and flowstone underground. Wind Cave National Park harbors pristine ancient water sources that contain trace materials from the Madison Aquifer. Coldwater Cave in Iowa has frequently flowing water that forms large flowstone features along the passageway. In Minnesota, Mystery Cave is a flood cave located within a secondary growth forest biome which contains calcite features from calcium-rich water. The comparison of cave environments allows for the examination of fluorescent cave water from currently flowing, old, or ancient water sources. Using primarily three different national/state park caves to form a holistic perspective, potential variables that aid in the flow of organics can be evaluated.

END