(Press-News.org) Tiny fragments of plastic have become ubiquitous in our environment and our bodies. Higher exposure to these microplastics, which can be inadvertently consumed or inhaled, is associated with a heightened prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases, according to new research being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

Researchers said the new findings add to a small but growing body of evidence that microplastic pollution represents an emerging health threat. In terms of its relationship with stroke risk, for example, microplastics concentration was comparable to factors such as minority race and lack of health insurance, according to the results.

“This study provides initial evidence that microplastics exposure has an impact on cardiovascular health, especially chronic, noncommunicable conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes and stroke,” said Sai Rahul Ponnana, MA, a research data scientist at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine in Ohio and the study’s lead author. “When we included 154 different socioeconomic and environmental features in our analysis, we didn’t expect microplastics to rank in the top 10 for predicting chronic noncommunicable disease prevalence.”

Microplastics—defined as fragments of plastic between 1 nanometer and 5 millimeters across—are released as larger pieces of plastic break down. They come from many different sources, such as food and beverage packaging, consumer products and building materials. People can be exposed to microplastics in the water they drink, the food they eat and the air they breathe.

The study examines associations between the concentration of microplastics in bodies of water and the prevalence of various health conditions in communities along the East, West and Gulf Coasts, as well as some lakeshores, in the United States between 2015-2019. While inland areas also contain microplastics pollution, researchers focused on lakes and coastlines because microplastics concentrations are better documented in these areas. They used a dataset covering 555 census tracts from the National Centers for Environmental Information that classified microplastics concentration in seafloor sediments as low (zero to 200 particles per square meter) to very high (over 40,000 particles per square meter).

The researchers assessed rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke and cancer in the same census tracts in 2019 using data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They also used a machine learning model to predict the prevalence of these conditions based on patterns in the data and to compare the associations observed with microplastics concentration to linkages with 154 other social and environmental factors such as median household income, employment rate and particulate matter air pollution in the same areas.

The results revealed that microplastics concentration was positively correlated with high blood pressure, diabetes and stroke, while cancer was not consistently linked with microplastics pollution. The results also suggested a dose relationship, in which higher concentrations of microplastic pollution are associated with a higher prevalence of disease. However, researchers said that evidence of an association does not necessarily mean that microplastics are causing these health problems. More studies are required to determine whether there is a causal relationship or if this pollution is occurring alongside another factor that leads to health issues, they said.

Further research is also needed to determine the amount of exposure or the length of time it might take for microplastics exposure to have an impact on health, if a causal relationship exists, according to Ponnana. Nevertheless, based on the available evidence, it is reasonable to believe that microplastics may play some role in health and we must take steps to reduce exposures, he said. While it is not feasible to completely avoid ingesting or inhaling microplastics when they are present in the environment, given how ubiquitous and tiny they are, researchers said the best way to minimize microplastics exposure is to curtail the amount of plastic produced and used, and to ensure proper disposal.

“The environment plays a very important role in our health, especially cardiovascular health,” Ponnana said. “As a result, taking care of our environment means taking care of ourselves.”

Ponnana will present the study, “Microplastic Concentration, Social, and Environmental Features and Their Association with Chronic Disease Prevalence: An Analysis Across U.S. Census Tracts,” Sunday, March 30, 2025, at 9:00 a.m. CT / 14:00 UTC in Moderated Poster Theater 2.

In a separate study presented at ACC.25, researchers from a different group reviewed the scientific literature and found that studies showed a strong correlation between microplastics in plaques in the heart’s arteries and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, suggesting that the presence of microplastics could play a role in the onset or exacerbation of serious heart problems. Eesha Nachnani of the University School of Nashville will present the study, “Plastic Perils: The Hidden Threat of Microplastics in Cardiovascular Health,” on Monday, March 31, 2025, at 9:00 a.m. CT / 14:00 UTC in South Hall.

ACC.25 will take place March 29-31, 2025, in Chicago, bringing together cardiologists and cardiovascular specialists from around the world to share the newest discoveries in treatment and prevention. Follow @ACCinTouch, @ACCMediaCenter and #ACC25 for the latest news from the meeting.

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) is the global leader in transforming cardiovascular care and improving heart health for all. As the preeminent source of professional medical education for the entire cardiovascular care team since 1949, ACC credentials cardiovascular professionals in over 140 countries who meet stringent qualifications and leads in the formation of health policy, standards and guidelines. Through its world-renowned family of JACC Journals, NCDR registries, ACC Accreditation Services, global network of Member Sections, CardioSmart patient resources and more, the College is committed to ensuring a world where science, knowledge and innovation optimize patient care and outcomes. Learn more at ACC.org.

###

END

Compared with those who spent most of their time in a single room, people with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) who were able to travel outside of their home without assistance were significantly less likely to be hospitalized or die within a year, according to a study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25). The findings underscore the value of supporting holistic care and encouraging people with heart failure to maintain an active lifestyle and engage with others ...

In addition to causing several types of cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV) appears to bring a significantly increased risk of heart disease and coronary artery disease, according to a study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

Evidence that HPV is linked with heart disease has begun to emerge only recently. This new study is the first to assess the association by pooling data from several global studies, totaling nearly 250,000 patients. Its findings bolster the evidence that a significant relationship exists ...

A new peer-reviewed studyi* published in Frontiers in Nutrition provides compelling evidence that pork can play a beneficial role in sustainable diets. The research, conducted by scientists at William & Mary, modeled the environmental and economic impacts of substituting various protein sources with pork in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults.

The findings suggest that pork performs similarly to poultry, seafood, eggs and legumes across key sustainability and agricultural resource indicators with a ± 1% change in land use, fertilizer nutrient use and pesticide use.

Modeled ...

Imagine a robot that can walk, without electronics, and only with the addition of a cartridge of compressed gas, right off the 3D-printer. It can also be printed in one go, from one material.

That is exactly what roboticists have achieved in robots developed by the Bioinspired Robotics Laboratory at the University of California San Diego. They describe their work in an advanced online publication in the journal Advanced Intelligent Systems.

To achieve this feat, researchers aimed to use the simplest technology available: a desktop ...

Mill Valley, CA – March 25, 2025 – The SynGAP Research Fund (SRF) dba Cure SYNGAP1 501(c)(3) announced a $130,000 grant to Dr. Vikaas Sohal at The Regents of The University of California, San Francisco. The grant supports research into new therapies for reversing cognitive deficits in SYNGAP1-related disorders (SRD) by enhancing key brain functions.

Dr. Sohal’s research focuses on cognitive flexibility—the ability to adapt behavior in response to environmental changes—a ...

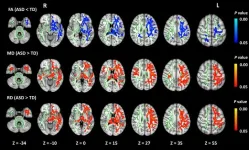

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a growing global concern, affecting approximately 2.8% of children in the United States and 0.7% in China. ASD is characterized by challenges in social interaction, communication difficulties, and repetitive behaviors, making early diagnosis critical for improving outcomes. However, current diagnostic methods rely primarily on behavioral observations, which may delay early interventions. Despite ongoing research, the structural and functional brain differences between children with ASD and typically developing (TD) children remain poorly understood.

Now, in a recent study published in NeuroImage and made available online on February ...

Siberia, a province located in Russia, is a significant geographical region playing a crucial role in the world’s carbon cycle. With its vast forests, wetlands, and permafrost regions (permanently frozen grounds), Siberia stores a considerable amount of carbon on a global scale. But climate change is rapidly altering Siberia’s landscape, shifting its vegetative distribution and accelerating the permafrost thaw. Classifying land cover is essential to predict future climatic changes, but accumulating land cover data in regions like ...

Life has evolved over billions of years, adapting to the changing environment. Similarly, enzymes—proteins that speed up biochemical reactions (catalysis) in cells—have adapted to the habitats of their host organisms. Each enzyme has an optimal temperature range where its functionality is at its peak. For humans, this is around normal body temperature (37 °C). Deviating from this range causes enzyme activity to slow down and eventually stop. However, some organisms, like bacteria, thrive in extreme environments, such as hot springs or freezing polar waters. These extremophiles have enzymes adapted to function in harsh conditions.

For ...

Obesity is linked to numerous health complications, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver disease. In a world where obesity rates continue to climb, researchers are constantly seeking effective, accessible solutions to this global health crisis. Interestingly, over the past few decades, scientists have begun to focus not only on what we eat but also on how we eat it.

While much attention has indeed focused on dietary content and caloric intake, emerging research suggests that eating behaviors—including meal duration, chewing speed, and number of bites taken—may ...

A new study published in The Journal of Immunology found that a high-salt diet (HSD) induces depression-like symptoms in mice by driving the production of a protein called IL-17A. This protein has previously been identified as a contributor to depression in human clinical studies.

“This work supports dietary interventions, such as salt reduction, as a preventive measure for mental illness. It also paves the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting IL-17A to treat depression,” shared Dr. Xiaojun Chen, a researcher at Nanjing ...