A new study led by researchers at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at Institute of Science Tokyo has uncovered a surprising role for calcium in shaping life’s earliest molecular structures. Their findings suggest that calcium ions can selectively influence how primitive polymers form, shedding light on a long-standing mystery: how life’s molecules came to prefer a single “handedness” (chirality).

Like our left and right hands, many molecules exist in two mirror-image forms. Yet life on Earth has a striking preference: DNA’s sugars are right-handed, while proteins are built from left-handed amino acids. This phenomenon, called homochirality, is essential for life as we know it—but how it first emerged remains a major puzzle in origins of life research.

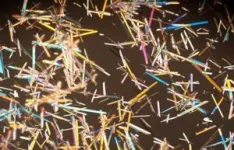

The team investigated tartaric acid (TA), a simple molecule with two chiral centers, to explore how early Earth’s environment might have influenced the formation of homochiral polymers. They discovered that calcium dramatically alters how TA molecules link together. Without calcium, pure left- or right-handed TA readily polymerises into polyesters, but mixtures containing equal amounts of both forms fail to form polymers readily. However, in the presence of calcium, this pattern reverses—calcium slows down the polymerisation of pure TA while enabling mixed solutions to polymerise.

“This suggests that calcium availability could have created environments on early Earth where homochiral polymers were favoured or disfavoured,” says Chen Chen, Special Postdoctoral Researcher at RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science (CSRS), who co-led the study. The researchers propose that calcium drives this effect through two mechanisms: first, by binding with TA to form calcium tartrate crystals, which selectively remove equal amounts of both left- and right-handed molecules from the solution; and second, by altering the polymerisation chemistry of the remaining TA molecules. This process could have amplified small imbalances in chirality, ultimately leading to the uniform handedness seen in modern biomolecules.

What makes this study especially intriguing is its suggestion that polyesters—simple polymers formed from molecules like tartaric acid—could have been among life’s earliest homochiral molecules, even before RNA, DNA, or proteins. “The origin of life is often discussed in terms of biomolecules like nucleic acids and amino acids,” ELSI’s Specially Appointed Associate Professor Tony Z. Jia, who co-led the study, explains. “However, our work introduces an alternative perspective: that ‘non-biomolecules’ like polyesters may have played a critical role in the earliest steps toward life.”

The findings also highlight how different environments on early Earth could have influenced which types of polymers formed. Calcium-poor settings, such as some lakes or ponds, may have promoted homochiral polymers, while calcium-rich environments might have favoured mixed-chirality polymers.

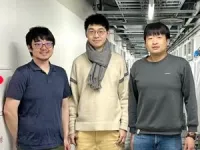

Beyond chemistry, this research bridges multiple scientific fields—biophysics, geology, and materials science—to explore how simple molecules interacted in dynamic prebiotic environments. The study is also the result of years of interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together researchers from seven countries across Asia, Europe, Australia, and North America.

“We faced significant challenges in integrating all of the complex chemical, biophysical, and physical analyses in a clear and logical way,” says project co-leader Ruiqin Yi of the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. “But thanks to the hard work and dedication of our team, we’ve uncovered a compelling new piece of the origins of life puzzle.” This research not only deepens our understanding of life’s beginnings on Earth but also suggests that similar processes could be at play on other planets, helping scientists search for life beyond our world.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Since the submission of the paper, the name of the university has changed from Tokyo Institute of Technology to Institute of Science Tokyo.

Co-author Chen Chen acquired most of the data during his period as a researcher at ELSI.

Reference

Chen Chena,1, Ruiqin Yib,1, Motoko Igisuc, Rehana Afrina, Mahendran Sithamparamd, Kuhan Chandrud,e,f, Yuichiro Uenoa,c,g, Linhao Sunh, Tommaso Laurenzii, Ivano Eberinii, Tommaso P. Fracciai, Anna Wangj,k,l,m, H. James Cleaves IIn,o, Tony Z. Jiaa,o,1, Primitive homochiral polyester formation driven by tartaric acid and calcium availability, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2419554122

a. Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI), Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-IE-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 152-8550, Japan

b. State Key Laboratory of Deep Earth Processes and Resources, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 9 Guangzhou, 510640, China

c. Institute for Extra-cutting-edge Science and Technology Avant-garde Research (X-star), Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), 2-15 Natsushima-cho, Yokosuka, 237-0061, Japan

d. Space Science Center (ANGKASA), Institute of Climate Change, National University of Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, Selangor 43650, Malaysia

e. Polymer Research Center (PORCE), Faculty of Science and Technology, National University of Malaysia, Selangor, 43600 Malaysia

f. Institute of Physical Chemistry, CENIDE, University of Duisburg-Essen, 45141 Essen, Germany

g. Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-IE-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 152-8550, Japan

h. WPI Nano Life Science (WPI-NanoLSI), Kanazawa University, Kakuma-machi, Kanazawa 920-1192, Japan

i. Dipartimento di Scienze Farmacologiche e Biomolecolari“Rodolfo Paoletti”, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20133, Milano, Italy

j. School of Chemistry, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

k. Australian Center for Astrobiology, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

l. RNA Institute, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

m. ARC Centre of Excellence for Synthetic Biology, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

n. Department of Chemistry, Howard University, Washington, District of Columbia 20059, USA

o. Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, 600 1st Ave, Floor 1, Seattle, WA 98104, USA

More information

Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) was established on October 1, 2024, following the merger between Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) and Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech), with the mission of “Advancing science and human wellbeing to create value for and with society.”

The Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) is one of Japan’s ambitious World Premiere International research centers, whose aim is to achieve progress in broadly inter-disciplinary scientific areas by inspiring the world’s greatest minds to come to Japan and collaborate on the most challenging scientific problems. ELSI’s primary aim is to address the origin and co-evolution of the Earth and life.

The World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) was launched in 2007 by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to foster globally visible research centers boasting the highest standards and outstanding research environments. Numbering more than a dozen and operating at institutions throughout the country, these centers are given a high degree of autonomy, allowing them to engage in innovative modes of management and research. The program is administered by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

END