(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (March 31, 2025) – A chance discovery led a team of scientists from Rice University, University of Cambridge and Stanford University to streamline the production of a material widely used in medical research and computing applications.

For over two decades, scientists working with a composite material known as PEDOT:PSS, used a chemical crosslinker to make the conductive polymer stable in water. While experimenting with ways to precisely pattern the material for applications in biomedical optics, Siddharth Doshi, a doctoral student at Stanford collaborating with Rice materials scientist Scott Keene, skipped adding the crosslinker and used a higher temperature while prepping the material. To his surprise, the resulting sample turned out to be stable on its own ⎯ no crosslinker needed.

“It was more of a serendipitous discovery because Siddharth was trying out processes very different to the standard recipe, but the samples still turned out fine,” Keene said. “We were like, ‘Wait! Really?’ This prompted us to look into why and how this worked.”

What Keene and his team found was that heating PEDOT:PSS beyond the usual threshold not only makes it stable without needing any crosslinker, but it also creates higher quality devices. This method, described in a recent study published in Advanced Materials, could make bioelectronic devices easier and more reliable to manufacture with potential applications in neural implants, biosensors and next-generation computing systems.

PEDOT:PSS is a blend of two polymers: one that conducts electronic charge and does not dissolve in water and another that conducts ionic charge and is water-soluble. Because it conducts both types of charges, PEDOT:PSS bridges the gap between living tissue and technology.

“It allows you to essentially talk the language of the brain,” said Keene, who researches advanced materials for smaller, high-resolution electrodes capable of both recording and stimulating neural activity with precision.

The human nervous system relies on ions ⎯ charged particles like sodium and potassium ⎯ to transmit signals, while electronic devices work with electrons. A material that can handle both is crucial for neural implants and other bioelectronic devices that need to translate biological activity into readable data and send signals without damaging sensitive tissue.

By eliminating the crosslinker, the research findings not only streamline the PEDOT:PSS fabrication process but also improve its performance. The new method produces a material with three times higher electrical conductivity and more consistent stability between batches ⎯ key advantages for medical applications.

The crosslinker worked by chemically bonding the two types of polymer strands in PEDOT:PSS together, creating an interconnected mesh. However, it still left some of the water-soluble strands exposed ⎯ a likely cause for the stability issues. Moreover, the crosslinker introduced variability and potential toxicity in the material.

In contrast, the higher heat stabilizes PEDOT:PSS by causing a phase change in the material. When heated beyond a certain temperature, the water-insoluble polymer reorganizes internally, pushing the water-soluble components to the surface, where they can be washed away. What remains is a thinner, purer and more stable conducting film.

“This method pretty much simplifies a lot of these problems that people have working with PEDOT:PSS,” Keene said. “It also essentially eliminates a potentially toxic chemical.”

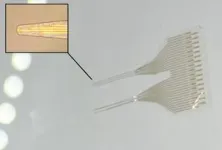

Margaux Forner, a doctoral student at Cambridge who is a first author on the paper along with Doshi, said that heat-treated bioelectronic devices such as transistors, spinal cord stimulators and electrocorticography arrays ⎯ implanted grids or strips of neuroelectrodes used to record brain activity ⎯ were easier to fabricate, more reliable and equally high performing to those fabricated using the crosslinker.

“The devices made from heat-treated PEDOT:PSS proved to be robust in chronic in vivo experiments, maintaining stability for over 20 days postimplantation,” Forner said. “Notably, the film maintained excellent electrical performance when stretched, highlighting its potential for resilient bioelectronic devices both inside and outside the body.”

The finding may help explain why previous efforts to use PEDOT:PSS in long-term neural implants, including those by Neuralink, ran into stability issues. By making PEDOT:PSS more reliable, this discovery could help advance neurotechnology, including implants to restore movement after spinal cord injuries and interfaces that link the brain to external devices.

Beyond simplifying fabrication, the team found a way to pattern PEDOT:PSS into microscopic 3D structures ⎯ a breakthrough that could further improve bioelectronic devices. Using a high-precision femtosecond laser, the researchers can selectively heat sections of the material, creating custom textures that enhance how cells interact with the devices.

“We are really excited about the ability to 3D-print the polymers at the microscale,” Doshi said. “This has been a major goal for the community as writing this functional material in 3D could let you interface with the 3D world of biology. Typically, this is done by combining PEDOT:PSS with different photosensitive binders or resins; however, these additions affect the properties of the material or are challenging to scale down to micron-length scales.”

In past research, Keene explored patterning grooves onto electrodes, finding that cells preferentially adhere to grooves on the same order as their length scale. In other words, “a 20 micron cell likes to grab on to 20 micron-sized textures,” he said.

This technique could be used to design neural interfaces that encourage better integration with surrounding tissue, improving signal quality and longevity.

Keene had also previously researched PEDOT:PSS in the context of neuromorphic memory devices used to accelerate artificial intelligence algorithms. Neuromorphic memory is a type or artificial memory that mimics how the brain retains information.

“It basically emulates the synaptic plasticity of your brain,” Keene said. “We can modify the connection between two terminals by controlling how conductive this material is; this is very similar to how your brain learns by strengthening or weakening synaptic connections between individual neurons.”

By unseating a long-standing assumption, the research not only made PEDOT:PSS easier to work with but also more powerful ⎯ a shift that could accelerate the development of safer, more effective neural implants and bioelectronic systems.

The research was supported by Stanford, Meta, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance at Stanford, the Joe and Clara Tsai Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, the National Science Foundation (2026822, 1542152), the Henry Royce Institute (EP/P024947/1, EP/R00661X/1), the United Kingdom Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/W017091/1) and the European Union (Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101022365). The content herein is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

-30-

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Peer-reviewed paper:

Thermal processing creates water-stable PEDOT:PSS films for bioelectronics | Advanced Materials | DOI: 10.1002/adma.202415827

Authors: Siddharth Doshi, Margaux O.A. Forner, Pingyu Wang, Salim El Hadwe, Amy T. Jin, Gerwin Dijk, Kenneth Brinson, Juhwan Lim, Antonio Dominguez-Alfaro, Carina Yi Jing Lim, Alberto Salleo, Damiano G. Barone, Guosong Hong, Mark. L. Brongersma, Nicholas A. Melosh, George G. Malliaras and Scott T. Keene

https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202415827

Access associated media files:

https://rice.box.com/s/ajkx7r9y8a5ql55sooe08u6feyupofee

About Rice:

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Texas, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of architecture, business, continuing studies, engineering and computing, humanities, music, natural sciences and social sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. Internationally, the university maintains the Rice Global Paris Center, a hub for innovative collaboration, research and inspired teaching located in the heart of Paris. With 4,776 undergraduates and 4,104 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 7 for best-run colleges by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by the Wall Street Journal and is included on Forbes’ exclusive list of “New Ivies.

END

Chance discovery improves stability of bioelectronic material used in medical implants, computing and biosensors

2025-03-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using artificial intelligence to calculate the heart’s biological age through ECG data predicts increased risk of mortality and cardiovascular events

2025-03-31

Vienna, Austria- 31 March 2025 - While everybody’s heart has an absolute chonological age (as old as that person is), hearts also have a theoretical ‘biological’ age1 that is based on how the heart functions. So someone who is 50 but has poor heart health could have a biological heart age of 60, while someone of 50 with optimal heart health could have a biological heart age of 40.

Researchers presenting a new study today at EHRA 2025, a scientific congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), demonstrated that by using artificial intelligence (AI) to analyse standard ...

“She loves me, she loves me not”: physical forces encouraged evolution of multicellular life, scientists propose

2025-03-31

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Humans like to think that being multicellular (and bigger) is a definite advantage, even though 80 percent of life on Earth consists of single-celled organisms – some thriving in conditions lethal to any beast.

In fact, why and how multicellular life evolved has long puzzled biologists. The first known instance of multicellularity was about 2.5 billion years ago, when marine cells (cyanobacteria) hooked up to form filamentous colonies. How this transition occurred and the benefits it accrued to the cells, though, is less than clear.

This week, a study originating from the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) presents a striking example of cooperative ...

The hidden superconducting state in NbSe₂: shedding layers, gaining insights

2025-03-31

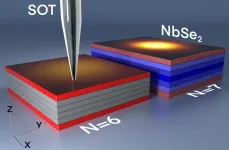

Researchers have discovered an unexpected superconducting transition in extremely thin films of niobium diselenide (NbSe₂). Published in Nature Communications, they found that when these films become thinner than six atomic layers, superconductivity no longer spreads evenly throughout the material, but instead becomes confined to its surface. This discovery challenges previous assumptions and could have important implications for understanding superconductivity and developing advanced quantum technologies.

Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have made a surprising discovery about how superconductivity ...

New AI models possible game-changers within protein science and healthcare

2025-03-31

Researchers have developed new AI models that can vastly improve accuracy and discovery within protein science. Potentially, the models will assist the medical sciences in overcoming present challenges within, e.g. personalised medicine, drug discovery, and diagnostics.

In the wake of broadly available AI tools, most technical and natural sciences fields are advancing rapidly. This is particularly true in biotechnology, where AI models power breakthroughs in drug discovery, precision medicine, gene editing, food security, and many other research areas.

One sub-field is proteomics – the study of proteins on a large scale – where ...

Highly accurate blood test diagnoses Alzheimer’s disease, measures extent of dementia

2025-03-31

A newly developed blood test for Alzheimer’s disease not only aids in the diagnosis of the neurodegenerative condition but also indicates how far it has progressed, according to a study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Lund University in Sweden.

Several blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease are already clinically available, including two based on technology licensed from WashU. Such tests help doctors diagnose the disease in people with cognitive symptoms, but do not indicate the ...

Mind the seismic gap: Understanding earthquake types in Guerrero, Mexico

2025-03-31

Plate temperature and water release can explain the occurrence of different types of earthquakes in Guerrera, Mexico. The Kobe University simulation study also showed that the shape of the Cocos Plate is responsible for a gap where earthquakes haven’t occurred for more than a century. The results are important for accurate earthquake prediction models in the region.

Where one tectonic plate is pushed down by another, the resulting stress is released in various tectonic events. There are catastrophic megathrust earthquakes, unnoticeable “slow slip events,” and continuous low-frequency “tectonic tremors,” and knowing ...

One hour’s screen use after going to bed increases your risk of insomnia by 59%, scientists find

2025-03-31

Scientists have found another reason to put the phone down: a survey of 45,202 young adults in Norway has discovered that using a screen in bed drives up your risk of insomnia up by 59% and cuts your sleep time by 24 minutes. However, social media was not found to be more disruptive than other screen activities.

“The type of screen activity does not appear to matter as much as the overall time spent using screens in bed,” said Dr Gunnhild Johnsen Hjetland of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, ...

Canada needs to support health research at home and abroad

2025-03-31

In the face of major changes to federal policy and funding in the United States, Canada should support Canadian researchers with adequate funding to ensure long-term research in health and science, argue authors in two articles published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

“As the US stands on the brink of tearing down its exemplary system for covering the full costs of research, Canada, with its flawed federal system for indirect costs, should heed the recent commissioned science policy report and a chorus of advocacy calling for an enhanced indirect cost system,” writes Dr. William Ghali, vice-president ...

Cannabis use disorder among insured pregnant women in the US between 2015-2020

2025-03-31

Cannabis use has been increasing during pregnancy, according to researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Previous research has observed that past-month cannabis use has more than tripled among pregnant women in the U.S. from 2002-2020 with self-reported cannabis use rising from 1.5 percent to 5.4 percent over the 18 years of tracking data. The findings are published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Medical guidelines recommend that pregnant women abstain from cannabis because of its link to an increased risk of adverse maternal ...

Education system needs overhaul to support school anxiety, psychologists say

2025-03-30

The UK education system must urgently change to be more understanding of school ‘refusers’, as returning to school might not be the right outcome for some children, psychologists say.

While much has been made of school attendance figures in recent months, a group of experts are suggesting not enough attention has been given to the experiences of parents and young people experiencing school distress.

In a new book, What Can We Do When School’s Not Working?, a parent and two ...