(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Mosquitoes have been transmitting the West Nile virus to humans in the United States for over 25 years, but we still don’t know precisely how the virus cycles through these pests and the other animals they bite.

A federally funded project aims to help pin down the process by using mathematical models to analyze how factors like temperature, light pollution, and bird and mosquito abundance affect West Nile virus transmission. The ultimate goal is to advise health departments of the best time of year to kill the bugs.

“I’m hopeful that what we will uncover in this grant will help us to better understand what’s driving West Nile virus transmission, and seasonal cycles of transmission, so we can determine when and where to direct control interventions to limit transmission and keep people healthy,” said Megan Meuti, principal investigator (PI) on the grant and associate professor of entomology at The Ohio State University.

The project, based on Ohio data but structured to develop models adaptable to other U.S. regions, is funded by a $3 million grant from the Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease program through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

West Nile virus (WNV) is the most common insect-borne virus in the U.S. Most infected people have minimal or mild flu-like symptoms, but about 1% can become seriously ill – especially those over 60 or people with chronic health problems – if the virus enters the brain.

Previous research gives us a general idea of how and when viral transmission occurs: As days get shorter, female mosquitoes from the Culex genus, known carriers of WNV, prepare for the winter dormancy period called diapause by fattening up on nectar from flowers – though they may take a viral infection they caught from birds with them into their winter downtime. After mosquitoes emerge from diapause in warmer months, more of them may become infected by taking blood meals from infected birds, and then transmit the virus when they feed on people, horses and other mammals.

Among the questions asked by Meuti’s team: How does viral transmission re-initiate each spring, and how does the virus’s presence persist in the environment during fall and winter?

The dormancy period appears to be delayed – or even prevented – by artificial light at night and heat in urban areas, according to previous studies in Meuti’s lab in the College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences. That disruption may mean the mosquitoes in cities are biting humans and animals longer into the fall, and also suggests urban and rural transmission patterns may differ.

“We know humans tend to get infected in the late summer and early fall, and other studies have shown that birds are infected before then, but we don’t really know where West Nile virus is going in the winter,” Meuti said.

The grant team started collecting mosquitoes and birds last fall and will continuously collect specimens for three years. Urban collection sites are located in Franklin and Lucas counties, and rural sites are in Union and Ottawa counties.

Bird trapping focuses on nine species known to be bitten by Culex mosquitoes: American robins, mourning doves, Northern cardinals, house sparrows, common grackles, European starlings, gray catbirds, Swainson’s thrushes and red-winged blackbirds. Researchers tag and release captured birds after collecting blood samples that will show their infection status – never infected, active WNV infection, or antibodies indicating they’ve been infected and recovered.

During the winter, researchers are collecting mosquitoes spending diapause in culverts to see if they’re already infected with the virus. Analysis of the blood contents in mosquitoes’ bellies will tell researchers what animals they’ve been biting – birds, horses or humans. Researchers will also sequence the RNA of the virus detected in mosquitoes.

The data and modeling will enable the team to test their hypotheses about how the transmission process plays out in rural and urban settings. In general, researchers predict mosquitoes are more likely to be infected with WNV over the winter in urban areas than in rural areas, suggesting that in rural areas, migratory birds are infecting mosquitoes, or the virus is spilling over from urban settings – or both.

“If RNA sequences are very similar from fall to spring, that would suggest the virus is staying local and, most likely, the way it’s staying local would be in the overwintering mosquitoes. But if we see differences in sequences from fall to spring, that would be more suggestive that it is a new WNV strain or a slightly different strain coming from migratory birds,” Meuti said.

“Once we have the models in place, we can predict what West Nile virus transmission might look like in a given year. And in partnership with local health departments and mosquito control districts, our ultimate goal is to understand what’s driving West Nile virus transmission and use this information to better predict when and where we can direct specific interventions.”

Co-PIs on the grant are Laura Pomeroy, assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Ohio State, who is building the mathematical models; Jaqueline Nolting, assistant professor of veterinary preventive medicine at Ohio State, who is analyzing biological samples from captured birds; and Brendan Shirkey, research coordinator for the Winous Point Marsh Conservancy, who is overseeing collection of birds and mosquitoes. Andrew Bowman, professor of veterinary preventive medicine, serves as senior personnel, designing experiments and assisting with data analysis.

#

Contact: Megan Meuti, Meuti.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

END

Genevieve Graaf spent years as a mental health social worker specializing in children and youth with complex behavioral health needs. Many had to travel to other states or hundreds of miles from family to access adequate medical care. Drawing on her experience, Dr. Graaf, an assistant professor of social work at The University of Texas at Arlington, has continuously sought ways to improve community-based support programs and ease the burden on families.

She will build on that work with her latest research through UT Arlington’s Center ...

Pancreatic cancer is projected to become the second-deadliest cancer by 2030. By the time it’s diagnosed, it’s often difficult to treat. So, for both individual patients and the general population, fighting pancreatic cancer can feel like a race against time. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor and Cancer Center Director David Tuveson offers a telling analogy:

“We all have moles on our skin. Most of your moles are fine. But some of your moles you have a dermatologist looking at to make sure it’s always fine. They ...

Bottom Line: Precancerous pancreatic lesions and some pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tumors harboring KRAS mutations had higher-than-normal expression of the FGFR2 protein, and FGFR2 inactivation delayed KRAS-mutated PDAC development in mice.

Journal in Which the Study was Published: Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research

Author: Claudia Tonelli, PhD, a research investigator in the laboratory of AACR Past President David A. Tuveson, MD, PhD, FAACR, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Background: PDAC is the most common ...

They say music is the universal language of humankind, but some stars in our galaxy exhibit their own rhythm, offering fresh clues into how they and our galaxy evolved over time.

According to an international team of researchers, including scientists from The Australian National University (ANU) and UNSW Sydney, some stars exhibit fluctuations in their brightness over time, which are caused by continuous ‘starquakes’.

These fluctuations can be translated into frequencies, which can be used to determine a star’s age and other properties ...

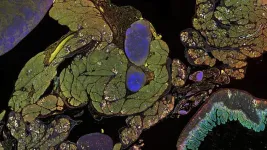

Investigation how microorganisms communicate enhances our understanding of the complex ecological interactions that shape our environment – a major focus of the Cluster of Excellence “Balance of the Microverse”. A research team of the Cluster at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology - Hans Knöll Institute (Leibniz-HKI) and the Friedrich Schiller University, Jena has studied the interaction between amoebae, bacteria, and plants. Researchers from the ...

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest that both nurse overtime and nurse agency hours are associated with increased rates of pressure ulcers, a measure that is one of the most sensitive to nursing care. In future research, hospitals could use their own data to track safe thresholds.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Patricia Pittman, PhD, email ppittman@gwu.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.2875)

Editor’s ...

About The Study: Spending on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) increased from 2018 to 2023, with the largest growth rates from 2022 to 2023. Although spending for certain GLP-1 RAs increased substantially, spending declined for others. This study estimated that more than $71 billion was spent on GLP-1 RAs and more than $50 billion on a product based on either semaglutide or tirzepatide molecules.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Stavros Tsipas, MA, email stavros.tsipas@ama-assn.org.

To ...

About The Study: In this cohort study with relatively low ambient ozone exposure, early-life ozone was associated with asthma and wheeze outcomes at age 4 to 6 and in mixture with other air pollutants but not at age 8 to 9. Regulating and reducing exposure to ambient ozone may help reduce the significant public health burden of asthma among U.S. children.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Logan C. Dearborn, MPH, email dearbl@uw.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.4121)

Editor’s ...

Researchers have made a new discovery that changes our understanding of Earth’s early geological history, challenging beliefs about how our continents formed and when plate tectonics began.

A study published in Nature on 2 April reveals that Earth's first crust, formed about 4.5 billion years ago, probably had chemical features remarkably like today’s continental crust.

This suggests the distinctive chemical signature of our continents was established at the very beginning of Earth’s history.

Professor Emeritus Simon ...

A study recently published in Nature indicates that human activities have a negative effect on the biodiversity of wildlife hundreds of kilometres away. A research collaboration led by the University of Tartu assessed the health of ecosystems worldwide, considering both the number of plant species found and the dark diversity – the missing ecologically suitable species.

For the study, over 200 researchers studied plants at nearly 5,500 sites in 119 regions worldwide, including all continents. At each site, they recorded all plant species on 100 m2 and identified the dark diversity – native species that could live there but were absent. ...