(Press-News.org) A new study, published today in Nature Chemistry by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Yale University, shows how common gut bacteria can metabolize certain oral medications that target cellular receptors called GPCRs, potentially rendering these important drugs less effective.

Drugs that act on GPCRs, or G protein-coupled receptors, include more than 400 medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of many common conditions such as migraines, depression, type 2 diabetes, prostate cancer and more.

“Understanding how GPCR-targeted drugs interact with human gut microbiota is critical for advancing personalized medicine initiatives,” said first author Qihao Wu, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Pitt School of Pharmacy, who started this project as a postdoctoral researcher at Yale. “This research could help open up new avenues for drug design and therapeutic optimization to ensure that treatments work better and safer for every individual.”

The effectiveness of a drug varies from person to person, influenced by age, genetic makeup, diet and other factors. More recently, researchers discovered that microbes in the gut can also metabolize orally administered drugs, breaking down these compounds into different chemical structures and potentially altering their efficacy.

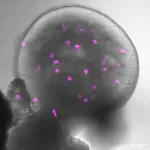

To learn more about which gut bacteria metabolize which drugs, Wu and the team at Yale, including the labs of Jason Crawford, Ph.D., Noah Palm, Ph.D., and Andrew Goodman, Ph.D., built a pipeline to rapidly and efficiently test this in the lab. They started by building a synthetic microbial community composed of 30 common bacterial strains found in the human gut. To tubes containing the bacteria, they added each of 127 GPCR-targeting drugs individually. Then they measured whether these drugs were chemically transformed and, if so, which compounds were produced.

The experiment showed that the bacterial mix metabolized 30 of the 127 tested drugs, 12 of which were heavily metabolized, meaning that concentrations of the original drug were greatly depleted because they were transformed into other compounds.

Next, the researchers looked more closely at one heavily metabolized drug called iloperidone, which is often used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. One bacterial strain in particular, Morganella morganii, inactivated iloperidone by transforming it a range of different compounds, both in the lab and in mice.

Overall, the findings suggest that specific gut bacteria could make GPCR-targeting drugs less effective by transforming them into other compounds.

However, Wu cautioned that more research is needed to understand potential impacts in people and that patients shouldn’t stop taking or change their medication without consulting their provider.

Although the study focused on a subset of GPCR drugs, the approaches could be applied more broadly to any orally administered chemicals, according to Wu.

“Another potential application of this pipeline is investigating interactions between gut bacteria and compounds found in food,” he said. “For example, we identified a couple of phytochemicals in corn that may affect gut barrier function. Notably, we observed that the gut microbiome could potentially protect us from these phytochemicals by detoxifying them.”

The next goal of the Wu Lab is to decode the metabolic pathway underlying these biotransformations, which could potentially identify strategies for improving therapeutic efficacy and enhancing food and drug safety.

Other authors on the study were Deguang Song, Ph.D., Yanyu Zhao, Andrew Verdegaal, Ph.D., Tayah Turocy, Ph.D., and Brianna Duncan-Lowey, Ph.D., all of Yale University.

This research was primarily supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1RM1GM141649). It was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (DP2DK125119 and R01AT010014).

END

Some gut bacteria could make certain drugs less effective

2025-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

PEPITEM sequence shows effects in psoriasis, comparable to steroid cream

2025-04-03

Birmingham scientists have shown that a sequence of just three amino acids may reduce the severity of psoriasis, when applied topically in an emollient cream.

The researchers, whose study is published in Pharmacological Research, identified the smallest part of a peptide (small protein) called PEPITEM, which occurs naturally in the body and regulates inflammation.

The study also showed that both PEPITEM and the three amino acid (tripeptide) sequence delivered a significant reduction in the severity of psoriasis, that is comparable to a steroid cream.

Psoriasis ...

Older teens who start vaping post-high school risk rapid progress to frequent use

2025-04-03

A new study has found that young vapers in the United States who begin using e-cigarettes after graduating from secondary/high school are likely to progress rapidly to frequent use. While US youths who start vaping during secondary/high school typically take about three years to progress to frequent use, this newly identified group of young adults who start vaping a bit later, after graduation (mean age = 20 years), tend to reach frequent use in about one year. ‘Frequent use’ is defined as using e-cigarettes on 20 or ...

Corpse flowers are threatened by spotty recordkeeping

2025-04-03

Commonly called the “corpse flower,” Amorphophallus titanum is endangered for many reasons, including habitat destruction, climate change and encroachment from invasive species.

Now, plant biologists from Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden have added a new threat to the list: incomplete historical records.

In a new study, scientists constructed the ancestry of corpse flowers living in collections at institutions and gardens around the world. They found a severe lack of consistent, standardized data. Without complete historical records, conservationists were unable to make informed decisions ...

Riding the AI wave toward rapid, precise ocean simulations

2025-04-03

AI has created a sea change in society; now, it is setting its sights on the sea itself.

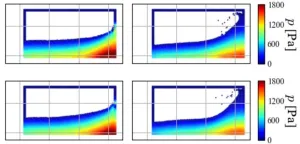

Researchers at Osaka Metropolitan University have developed a machine learning-powered fluid simulation model that significantly reduces computation time without compromising accuracy. Their fast and precise technique opens up potential applications in offshore power generation, ship design and real-time ocean monitoring.

Accurately predicting fluid behavior is crucial for industries relying on wave and tidal energy, as well as for design of maritime structures and vessels. ...

Are lifetimes of big appliances really shrinking?

2025-04-03

Big appliances, like washing machines, ovens and refrigerators, are a major investment for many households. Consumers hope that these appliances will last for decades. More and more, however, people have the perception that these big-ticket items might not be lasting as long as they once did.

But when Kamila Krych looked at actual trends in product lifetimes as a part of her PhD research at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Industrial Ecology Programme, she found that wasn’t quite true.

“Despite what people think, there is no evidence that product lifetimes are decreasing,” she said. “Many people think that products have been becoming ...

Pink skies

2025-04-03

Organoids have revolutionized science and medicine, providing platforms for disease modeling, drug testing, and understanding developmental processes. While not exact replicas of human organs, they offer significant insights. The Siegert group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) presents a new organoid model that reveals details of the developing nervous system’s response to viral infections, such as Rubella. This model could influence pharmaceutical testing, particularly benefiting drug safety for pregnant ...

Monkeys are world’s best yodellers - new research

2025-04-02

A new study has found that the world’s finest yodellers aren’t from Austria or Switzerland, but the rainforests of Latin America.

Published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B and led by experts from Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) and the University of Vienna, the research provides significant new insights into the diverse vocal sounds of non-human primates, and reveals for the first time how certain calls are produced.

Apes and monkeys possess special anatomical structures in their throats called vocal membranes, which disappeared from humans through evolution to allow for more stable speech. However, ...

Key differences between visual- and memory-led Alzheimer’s discovered

2025-04-02

Differences in the distribution of certain proteins and markers in the brain may explain why some people first experience vision changes instead of memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease, finds a new study by UCL researchers.

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a rare form of Alzheimer’s disease that, rather than causing problems with memory, leads to difficulties with reading, navigating, and recognising objects. Studies suggest that one in 10 patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a form which is visual, rather than memory led.

As well as presenting with unusual symptoms, ...

% weight loss targets in obesity management – is this the wrong objective?

2025-04-02

New research to be presented at this year’s European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2025, Malaga, Spain, 11-14 May) suggests that weight loss programmes targeting a particular % weight loss are often failing, and that other factors should be considered including improvement of obesity-related complications, enhancing quality of life and overall physical and social functioning. The research is by an international team including Dr Sanjeev Sockalingam, Obesity Canada and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and colleagues.

Identifying the most appropriate targets for obesity management is crucial due to the complexity of obesity ...

An app can change how you see yourself at work

2025-04-02

By most accounts, confidence is a prerequisite for workplace success. What if it could be trained, even subtly rewired, using something as simple as a smartphone app?

That’s the premise behind a first-of-its-kind study from the University of California, Riverside, where psychologists tested whether workers could reshape their self-image through a digital tool that reinforces positive beliefs.

The findings, published in Computers in Human Behavior Reports, suggest they can—and that belief systems, often assumed to be deeply ...