(Press-News.org) In the largest study of its kind to date, a team of international researchers has investigated how pharmaceutical pollution affects the behaviour and migration of Atlantic salmon.

The study, led by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, revealed that commonly detected environmental levels of clobazam – a medication often prescribed for sleep disorders – increased the river-to-sea migration success of juvenile salmon in the wild.

The researchers also discovered that clobazam shortened the time it took for juvenile salmon to navigate through two hydropower dams along their migration route – obstacles that typically hinder successful migration.

Dr Marcus Michelangeli from Griffith University's Australian Rivers Institute, who was a key contributor to the study published in Science, emphasised the increasing threat of pharmaceutical pollution to wildlife and ecosystems worldwide.

“Pharmaceutical pollutants are an emerging global issue, with over 900 different substances having now been detected in waterways around the world,” Dr Michelangeli said.

“Of particular concern are psychoactive substances like antidepressants and pain medications, which can significantly interfere with wildlife brain function and behaviour.

Dr Michelangeli noted that the study’s real-world focus sets it apart from previous research.

“Most previous studies examining the effects of pharmaceutical pollutants on wildlife have been conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which don’t fully capture the complexities of natural environments,” he said.

“This study is unique because it investigates the effects of these contaminants on wildlife directly in the field, allowing us to better understand how exposure impacts wildlife behaviour and migration in a natural context.

“While the increased migration success in salmon exposed to clobazam might seem like a beneficial effect, it is important to realise that any change to the natural behaviour and ecology of a species is expected to have broader negative consequences both for that species and the surrounding wildlife community.”

The research team employed innovative slow-release pharmaceutical implants and animal-tracking transmitters to monitor how exposure to clobazam and the opioid painkiller tramadol – another common pharmaceutical pollutant – affected the behaviour and migration of juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Sweden’s River Dal as they migrated to the Baltic Sea.

A follow-up laboratory experiment also found that clobazam altered shoaling behaviour, indicating that the observed migration changes in the wild may result from drug-induced shifts in social dynamics and risk-taking behaviour.

Dr Michelangeli explained that predicting the full extent of these impacts remains challenging

“When you consider realistic exposure scenarios where entire ecosystems are exposed – encompassing multiple species and a diversity of contaminants – the potential consequences become even more complex,” he said.

While the recent decline of Atlantic salmon is primarily attributed to overfishing, habitat loss, and fragmentation – leading to their endangered status – the study highlights how pharmaceutical pollution could also influence key life-history events in migratory fish.

Dr Michelangeli pointed out that many pharmaceuticals persist in the environment due to poor biodegradability and insufficient wastewater treatment. However, there is hope.

“Advanced wastewater treatment methods are becoming more effective at reducing pharmaceutical contamination, and there is promising potential in green chemistry approaches,” he said.

“By designing drugs that break down more rapidly or become less harmful after use, we can significantly mitigate the environmental impact of pharmaceutical pollution in the future.”

The study ‘Pharmaceutical pollution influences river-to-sea migration in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)’ has been published in Science.

END

Drug pollution alters migration behavior in salmon

2025-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists decode citrus greening resistance and develop AI-assisted treatment

2025-04-10

In a groundbreaking study published in Science, a research team led by Prof. YE Jian from the Institute of Microbiology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has identified the first mechanism of citrus resistance to citrus greening disease, or huanglongbing (HLB).

Utilizing artificial intelligence (AI), the team has also developed antimicrobial peptides that offer a promising therapeutic approach to combat the disease. This discovery addresses a long-standing challenge in the agricultural community—the absence of naturally occurring HLB-resistant genes in citrus.

Citrus ...

Venom characteristics of a deadly snake can be predicted from local climate

2025-04-10

Local climate can be used to predict the venom characteristics of a deadly snake that is widespread in India, helping clinicians to provide targeted therapies for snake bite victims, according to a study publishing April 10 in the open-access journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases by Kartik Sunagar and colleagues at the Indian Institute of Science.

Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) is found across the Indian subcontinent and is responsible for over 40% of snake ...

Brain pathway links inflammation to loss of motivation, energy in advanced cancer

2025-04-10

The fatigue and lack of motivation that many cancer patients experience near the end of life have been seen as the unavoidable consequences of their declining physical health and extreme weight loss. But new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis challenges that long-held assumption, showing instead that these behavioral changes stem from specific inflammation-sensing neurons in the brain.

In a study published April 11 in Science, the researchers report that they identified a direct connection between cancer-related inflammation ...

Researchers discover large dormant virus can be reactivated in model green alga

2025-04-10

Researchers had been studying the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii for decades without seeing evidence of an active virus within it — until a pair of Virginia Tech researchers waded into the conversation.

Maria Paula Erazo-Garcia and Frank Aylward not only found a virus in the alga but discovered the largest one ever recorded with a latent infection cycle, meaning it goes dormant in the host before being reactivated to cause disease.

“We’ve known about latent infections for a long time,” said Aylward, associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences. ...

New phase of the immune response uncovered

2025-04-10

The research groups led by Wolfgang Kastenmüller and Georg Gasteiger employed innovative microscopy techniques to observe how specific immune cells, known as T-cells, are activated and proliferate during a viral infection. Their findings revealed novel mechanisms: the immune system amplifies its defense cells in a far more targeted way than previously believed.

T-Cells Proliferate and Specialize During the Immune Response

T-cells are crucial defense cells in the immune system. To effectively ...

Drawing board rather than salt shaker

2025-04-10

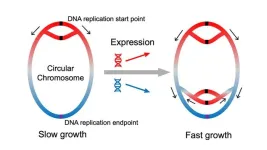

Bioinformaticians from Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU) and the university in Linköping (Sweden) have established that the genes in bacterial genomes are arranged in a meaningful order. In the renowned scientific journal Science, they describe that the genes are arranged by function: If they become increasingly important at faster growth, they are located near the origin of DNA replication. Accordingly, their position influences how their activity changes with the growth rate.

Are genes distributed randomly along the bacterial chromosome, as if scattered from a salt shaker? This opinion, which is held by a majority of researchers, has ...

Engineering invites submissions on AI for engineering

2025-04-10

Artificial intelligence (AI) is playing an increasingly pivotal role in revolutionizing the field of engineering, triggering a new era of technological and industrial evolution. A series of recent breakthroughs in areas like natural language processing, computer vision, and machine learning, with the Nobel Prize-winning work in artificial neural networks and protein structure prediction serving as prime examples, have effectively bridged the gap between the physical and digital worlds. The emergence of general AI technologies, especially large language models, has given rise ...

In Croatia’s freshwater lakes, selfish bacteria hoard nutrients

2025-04-10

Bacteria play key roles in degrading organic matter, both in the soil and in aquatic ecosystems. While most bacteria digest large molecules externally, allowing other community members to share and scavenge, some bacteria selfishly take up entire molecules before digesting them internally. In a paper publishing April 10 in the Cell Press journal Cell Reports, researchers document “selfish polysaccharide uptake” in freshwater ecosystems for the first time. In Croatia’s Kozjak and Crniševo Lakes, they found that nutrient hoarding allows selfish species ...

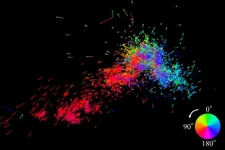

Research suggests our closest neighboring galaxy may be being torn apart

2025-04-10

A team led by Satoya Nakano and Kengo Tachihara at Nagoya University in Japan has revealed new insights into the motion of massive stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), a small galaxy neighboring the Milky Way. Their findings suggest that the gravitational pull of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), the SMC’s larger companion, may be tearing the smaller one apart. This discovery reveals a new pattern in the motion of these stars that could transform our understanding of galaxy evolution and interactions. The results were published ...

Researchers identify factors in early-life linked to body fat in South Asian children

2025-04-10

Researchers at McMaster University have identified six key factors in the first three years of life that influence the trajectory of obesity in South Asian children.

The findings offer parents, primary care practitioners and policymakers new insights into addressing childhood obesity for a group of children who have a higher prevalence of abdominal fat and cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as a predisposition to diabetes.

“We know that current measures of childhood obesity such as the body mass index (BMI) don’t work well for South Asians because of the so called ‘thin-fat’ phenotype: South Asian newborns are characterized as low birth weight, but proportionally ...