Archaeologists measured and compared the size of 50,000 ancient houses to learn about the history of inequality -- they found that it’s not inevitable

2025-04-14

(Press-News.org) We’re living in a period where the gap between rich and poor is dramatic, and it’s continuing to widen. But inequality is nothing new. In a new study published in the journal PNAS, researchers compared house size distributions from more than 1,000 sites around the world, covering the last 10,000 years. They found that while inequality is widespread throughout human history, it’s not inevitable, nor is it expressed to the same degree at every place and time.

“This paper is part of a larger study in which over 50,000 houses have been analyzed to use differentials in house sizes as a metric for wealth inequality over time, on six continents,” says Gary Feinman, the MacArthur Curator of Mesoamerican, Central American, and East Asian Anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago, and the paper’s lead author. “This is an unprecedented data set in archaeology, and it allows us to empirically and systematically look at patterns of inequality over time.”

The paper Feinman led delves into a comparison of the extent of inequality at different localities (mostly archaeological) to figure out how things changed over time. “While there is not one unilinear sequence of change in wealth inequality over time, there are interpretable patterns and trends that cross-cut time and space. What we see is not just noise or chaos,” says Feinman.

The variation that the researchers found challenges long-held views across history and the social sciences that we can use ancient Greece and Rome, or the medieval history of Europe as generalized representations of humanity’s past. “There are a lot of things that have been presumed for centuries— for example, that inequality rises inevitably,” says Feinman. “The traditional thinking expects that once you get larger societies with formal leaders, or once you have farming, inequality is going to go way up. These ideas have been held for hundreds of years, and what we find is that it’s more complicated than that— high degrees of inequality are not inevitable in large societies. There are factors that may make it easier to happen or increase to high degrees, but these factors can be leveled off or modified by different human decisions and institutions.”

“Variability in the sizes of houses may not be the full extent of wealth differences, but it's a consistent indicator of the degree of economic inequality that can be applied across time and space,” says Feinman. “I know from my own archaeological fieldwork in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, that almost always, the larger the house, the more elaborate the house, with special features and thicker walls.”

To quantify and compare economic inequality in different places, at different points in history, the researchers used the variable distributions of house sizes at more than 1000 settlements to calculate a Gini coefficient for each site conducted statistical analyses in which they examined the relationship between the amount of inequality in a society and the political complexity of that society. The Gini coefficient is a commonly employed metric to assess inequality that ranges between 0 (complete equality) and 1 (maximal inequality).The coefficients for each locality were then compared across time and space to examine trends in inequality and assess how it varied in relation to population, political organization, and other potential causal factors.

The investigators then looked at these trends in the Gini values in the context of the size of the sites that were compared and how complex the hierarchical structure of governance was. They found that even while populations have risen over the years, inequality hasn’t always increased in a uniform way.

“The measure of inequality we found in these sites is quite variable, which suggests that there’s not one homogenized pattern,” says Feinman. In other words, contrary to traditional scholarly thinking, there’s no one-size-fits-all explanation for why societies become economically unequal.

“Human choice and governance and cooperation have played a role in damping down inequality at certain times and places, and that is what accounts for this variability in time and space,” says Feinman. “And if inequality isn't inevitable when human aggregations get larger and governmental structures get more hierarchical, then there is a suite of implications for how we view the present and how we look at the past. Although history has shown us that elements of technology and population growth can raise the potential for inequality at certain times and places, that potential is not always realized, as people have implemented leveling mechanisms and systems of governance that mute that potential. The often-expressed views that certain economic, demographic, or technological conditions or factors make great wealth disparities inevitable simply are not borne out by our global past.”

###

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2025-04-14

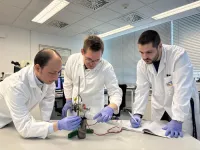

LA JOLLA (April 18, 2025)—Industrial farming practices often deplete the soil of important nutrients and minerals, leaving farmers to rely on artificial fertilizers to support plant growth. In fact, fertilizer use has more than quadrupled since the 1960s, but this comes with serious consequences. Fertilizer production consumes massive amounts of energy, and its use pollutes the water, air, and land.

Plant biologists at the Salk Institute are proposing a new solution to help kick this unsustainable fertilizer habit.

In a new study, the researchers identified ...

2025-04-14

EMBARGOED UNTIL 15.00 US ET (20.00 BST) ON MONDAY 14 APRIL 2025

The study lead by Professor Dan Lawrence, of Durham University in the UK, found that across ten millennia, more unequal distributions of wealth correlated with longer-term human settlement.

However, the team are keen to stress that one factor is not causally dependent on the other, giving hope that humankind’s survival is not linked to ever increasing inequality.

The research is part of a Special Feature of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), entitled Global Dynamics of Wealth Inequality.

Sustainability is defined by the ...

2025-04-14

University of California, Davis researchers have developed a new, neuroplasticity-promoting drug closely related to LSD that harnesses the psychedelic’s therapeutic power with reduced hallucinogenic potential.

The research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, highlights the new drug’s potential as a treatment option for conditions like schizophrenia, where psychedelics are not prescribed for safety reasons. The compound also may be useful for treating other neuropsychiatric ...

2025-04-14

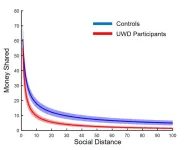

Are there areas of the brain, which regulate prosocial, altruistic behaviour? Together with colleagues from the universities in Lausanne, Utrecht and Cape Town, researchers from Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU) have studied a very special group of patients and established that the “basolateral amygdala” (part of the limbic system) plays an important role in this. In the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), they describe that this region calibrates social behaviour.

Prosocial ...

2025-04-14

PULLMAN, Wash. — Wealth inequality began shaping human societies more than 10,000 years ago, long before the rise of ancient empires or the invention of writing.

That’s according to a new study led by Washington State University archaeologist Tim Kohler that challenges traditional views that disparities in wealth emerged suddenly with large civilizations like Egypt or Mesopotamia. The research is part of a special issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, co-edited by Kohler and Amy Bogaard, an archaeologist at Oxford University in England.

Drawing on data from over 47,000 residential ...

2025-04-14

If the archaeological record has been correctly interpreted, stone alignments in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge are remnants of shelters built 1.7 million years ago by Homo habilis, an extinct species representing one of the earliest branches of humanity’s family tree.

Archaeological evidence that is unambiguously housing dates to more than 20,000 years ago—a time when large swaths of North America, Europe and Asia were covered in ice and humans had only recently begun living in settlements.

Between that time and the dawn of industrialization, the archaeological record is rich not only with evidence of settled life represented by housing, but also with evidence ...

2025-04-14

It is one of the most significant trends in materials science: materials that consist of only a single layer of atoms, so-called “2D materials”, often show completely different properties than thicker layers consisting of the same atoms. This field of research began with the Nobel Prize-winning material graphene. Now, research is being conducted into the material class of MXenes (pronounced Maxenes), which consist mainly of titanium and carbon, by TU Wien (Vienna) together with the companies CEST and AC2T.

These MXenes have properties that ...

2025-04-14

Philadelphia, April 14, 2025 – Researchers have demonstrated the potential of the innovative optical genome mapping (OGM) technique for the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic management of multiple myeloma. This new study in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, published by Elsevier, details how this novel method can establish the cytogenomic profile of the tumor on a scale suitable for routine practice in cytogenetics laboratories.

Multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer that forms in plasma cells (a type of white blood cells), is the second ...

2025-04-14

Major reallocation of healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that elective surgery in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) was significantly reduced, so that those needing urgent, lifesaving and emergency surgery could be treated. However, this prioritisation of the most severely ill children did not increase overall post-operative complications rates or death, a study led by the University of Bristol has shown.

The research, published in Open Heart, suggests that prioritising surgery for younger and more critically ill children may be appropriate when there is a sudden disruption of usual care. The ...

2025-04-14

When you’re on a sandy beach or the banks of a river, transformed by rolling waves or slightly still waters, it’s likely you’re not thinking about what happens just beneath the surface, where dirt and pollution are swirling and traveling through to new destinations.

But Hanadi Rifai does. The Moores Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and director of the Hurricane Resilience Research Institute, has spent two decades examining Galveston Bay – its tides, currents ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Archaeologists measured and compared the size of 50,000 ancient houses to learn about the history of inequality -- they found that it’s not inevitable