(Press-News.org)

A new discovery could pave the way for more effective cancer treatment by helping certain drugs work better inside the body.

Scientists at Duke University School of Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and University of Arkansas have found a way to improve the uptake of a promising class of cancer-fighting drugs called PROTACs, which have struggled to enter cells due to their large size.

The new method works by taking advantage of a protein called CD36 that helps pull substances into cells. By designing drugs to use this CD36 pathway, researchers delivered 7.7 to 22.3 times more of the drug inside cancer cells, making the treatment up to 23 times more potent than before, according to the study published April 17 in Cell.

Data from mouse studies shows this enhanced uptake led to stronger tumor suppression without making the drugs harder to dissolve or less stable.

The strategy called chemical endocytic medicinal chemistry (CEMC) takes advantage of a natural process where cells “swallow” molecules called endocytosis. It could change the future of drug design – especially for drugs that were once considered too big to work.

“This discovery is important because it could rescue many drugs that were previously considered unusable due to poor absorption and turn them into clinically useful treatments for diseases,” said study author Hui-Kuan Lin, PhD, a cancer biology researcher and professor in the Department of Pathology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Most drug development focuses on tweaking molecules to improve their ability to slip through cell membranes by passive diffusion. But the new strategy takes a different path: using cell surface receptors like CD36 to actively bring drugs inside. CD36 is a protein abundantly found on the surface of cells in the intestine, skin, lungs, eyes, and even some brain cells.

The strategy was particularly successful for a class of complex, large-sized drugs known as bRo5 molecules, such as PROTACs, a type of targeted cancer therapy that breaks down proteins in cells.

These molecules usually have a hard time getting into cells because they’re very large – over 500 dalton (Da). Until now, it was unclear how they entered cells at all. In this study, the PROTAC drugs tested were over 1,000 Da, which is enormous by pharmaceutical standards.

But the modified PROTACs not only entered cells more efficiently but also showed greater tumor-fighting power, all while maintaining their stability and solubility – two crucial factors for effective medicines.

In doing so, the strategy overcomes the ‘Rule of 5’ barrier for drug development which holds that drugs larger than 500 Da are generally ineffective because they struggle to enter cells.

“This was completely unexpected in the research field,” said study author Hong-yu Li, PhD, professor of medicinal chemistry and chemical biology in the Department of Pharmacology at UT-San Antonio.

“For decades it was thought that molecules this large couldn’t cross membranes effectively, since the endocytic cellular uptake of chemical compounds was unknown,” Li said. “Through chemistry and biology, we identified CD36 as a protein for uptake and optimized drugs better engaging with CD36 to internalize these drugs to more efficiently reach target protein.”

The results were independently reproduced by each of the teams involved in the study, including lab work led by study author, Zhiqiang Qin, MD, PhD, associate professor of pathology at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

The findings will need to undergo further testing and evaluation in clinical trials before the strategy can be used in medications given to patients during cancer treatment.

New Path for Drug Discovery

Traditional cancer drugs, like kinase inhibitors, are designed to block just the enzymatic activity of a target protein – basically, they stop the protein from doing one specific job. But they don’t get rid of the protein itself.

However, many proteins have other functions beyond their enzyme activity and those can still help cancer grow and spread. That means the drug isn’t fully stopping the cancer, and over time, the cancer can become resistant to the drug.

“Since PROTACs degrade its target protein and activity, it is expected to achieve more potent efficacy and reduce the possibility of drug resistance in the future,” said Lin, who is also a professor of cancer biology and pharmacology at Duke.

PROTACs are being developed to treat cancer, neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, and other conditions where eliminating harmful proteins could make a major difference. Eight oral PROTAC drugs are being tested in clinical trials — including a recent Phase 3 trial exploring one as a first-line therapy to break down estrogen receptors in breast cancer tumors.

But the new drug design extends beyond cancer treatment. Researchers say the findings suggest that many other large and complex drugs could be improved using the same strategy.

Additional study authors include co-lead authors Zhengyu Wang, of UT-San Antonio, and Bo-Syong Pan and Rajesh Kumar Manne, of Duke.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA277682) (R01 CA139429); University of Texas Health San Antonio; Arkansas Research Alliance Endowed Chair Fund; Duke University School of Medicine; Duke Fred and Janet Sanfilippo Distinguished Professorship ; Arkansas Bioscience Institute; Arkansas Breast Cancer Research Program Pilot Award and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

END

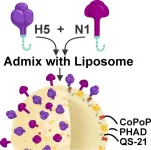

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A vaccine under development at the University at Buffalo has demonstrated complete protection in mice against a deadly variant of the virus that causes bird flu.

The work, detailed in a study published today (April 17) in the journal Cell Biomaterials, focuses on the H5N1 variant known as 2.3.4.4b, which has caused widespread outbreaks in wild birds and poultry, in addition to infecting dairy cattle, domesticated cats, sea lions and other mammals.

In the study, scientists describe a process they’ve developed for creating doses with precise ...

(WASHINGTON, April 17, 2024) — Hydroxyurea remains effective long-term in reducing emergency department visits and hospital days for children living with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to new research published in Blood Advances.

“This is one of the first large, real-world, long-term studies to assess the efficacy of hydroxyurea outside of a controlled setting,” said study author Paul George, MD, a pediatric hematology/oncology fellow and PhD candidate at Emory University School of Medicine and Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Children’s ...

Florida Atlantic University has been recognized as a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Research (CAE-R) by the National Security Agency (NSA) and its partners in the National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity (NCAE-C). This prestigious designation, awarded through the academic year 2030, affirms the university’s leadership and innovation in the field of cybersecurity research at the doctoral level.

This recognition places FAU among an elite group of institutions nationwide that have demonstrated a sustained commitment to cutting-edge research in cyber defense and security. The CAE-R designation is awarded to universities whose programs meet rigorous ...

A research team has decoded the genome of historic potato cultivars and used this resource to develop an efficient method for analysis of hundreds of additional potato genomes.

Potatoes are a staple food for over 1.3 billion people. But despite their importance for global food security, breeding successes have been modest. Some of the most popular potato cultivars were bred many decades ago. The reason for this limited success is the complex genome of the potato: there are four copies of the genome in each cell instead of just two. ...

Research Highlights:

Among adults ages 18-49 (median age of 41 years) who were born with a hole in the upper chambers of their heart known as patent foramen ovale (PFO), strokes of unknown cause were more strongly associated with nontraditional risk factors, such as migraines, liver disease or cancer, rather than more typical factors such as high blood pressure.

Migraine with aura was the top factor linked to strokes of unknown causes, also called cryptogenic strokes, especially among women.

Embargoed ...

Three consecutive years of drought contributed to the ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’, a pivotal moment in the history of Roman Britain, a new Cambridge-led study reveals. Researchers argue that Picts, Scotti and Saxons took advantage of famine and societal breakdown caused by an extreme period of drought to inflict crushing blows on weakened Roman defences in 367 CE. While Rome eventually restored order, some historians argue that the province never fully recovered.

The ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’ of 367 CE was one of the most severe threats to Rome’s hold on Britain since the Boudiccan revolt three centuries earlier. Contemporary sources indicate that components ...

If you have ever chickened out of eating chicken, your unease may not have been unreasonable.

Osaka Metropolitan University researchers have detected alarming rates of Escherichia albertii, an emerging foodborne pathogen, in retail chicken meat in Bangladesh. Their findings show extensive contamination and significant antimicrobial resistance, underscoring the potential risks to public health.

E. albertii is a less known but probably not less dangerous relative of E. coli. First described in Bangladesh in 2003, this bacterium ...

The UK pedigree dog population shrank by a yearly decline of 0.9% between 1990 and 2021, according to research published in Companion Animal Genetics and Health. The study highlights a rise in the populations of crossbreeds and imported pedigree dogs since 1990, but finds that only 13.7% of registered domestic pedigree dogs were used for breeding between 2005 and 2015.

There are more than 400 breeds of dogs globally, characterised by different appearances and behaviours. While the overall population of pet dogs in the UK ...

Climate change may significantly impact arsenic levels in paddy rice, a staple food for millions across Asia, reveals a new study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. The research shows that increased temperatures above 2°C, coupled with rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels, lead to higher concentrations of inorganic arsenic in rice, potentially raising lifetime health risks for populations in Asia by 2050. Until now, the combined effects of rising CO2 and temperatures on arsenic accumulation in rice have not been studied in detail. The research done ...

European research led by University College London (UCL), together with Amsterdam UMC and the University of Basel shows that a significant proportion of patients who suffer a stroke due to carotid artery narrowing can be treated with medication only. A risky carotid artery operation, currently still the standard treatment for many patients, may then no longer be necessary for this group of patients. This research, published today in the Lancet Neurology, may lead to the global guidelines for the treatment of these patients being adjusted.

In the Netherlands, about 2,000 people with carotid artery stenosis ...