(Press-News.org) New experiments show that common scientific rules can apply to significantly different phenomena operating on vastly different scales.

The results raise the possibility of making discoveries pertaining to phenomena that would be too large or impractical to recreate in the laboratory, said Cheng Chin, associate professor in physics and the James Franck Institute at the University of Chicago. Chin and associates Chen-Lung Hung, Xibo Zhang and Nathan Gemelke published their results in the Jan. 26 Advance Online Publication (Feb. 10 print edition) of the journal Nature.

Chin aspires to simulate the impossibly hot conditions that followed the big bang, during the earliest moments of the universe, by using an ultracold vacuum chamber in his laboratory. "It's fascinating to think about all these connections," he said.

The UChicago experiments demonstrate the validity of two widely discussed topics in the physics community today: scale invariance and universality.

Theoretical physicist Lev Pitaevskii had predicted that scale invariance would apply to a two-dimensional, cold-atom gas in 1997. Scale invariance means that the properties of a given phenomenon will remain the same, no matter how much its size is expanded or contracted. This contrasts sharply the three-dimensional world of everyday life, where dynamics change dramatically.

In the biological world, for example, scale invariance does not apply to complex organisms like humans, but exists in simple biological structures like nautilus shells, ferns and even broccoli. In physics, special cases also exist that exhibit scale invariance. Fractal structures have been observed in nature, which manifest similar structures whether magnified 10, 1,000 or a million times.

"There are only a few systems in nature that can display this kind of scale invariance, and we have shown that our two-dimensional system belongs to this very special class," Chin explained.

"Once you identify these special cases and see how they are all linked together, then you can bring all these physical phenomena under the same umbrella," Chin said. "Now they can be fully described using the same language."

Exotic transformation

The universality concept applies to matter that undergoes smooth phase transitions. In the physics of everyday life, a phase transition occurs when water freezes to ice on a cold winter day. The phase transition in the UChicago experiment is more exotic: In the experiment, cesium atoms transform from a gas to a superfluid, a form of matter that exists only at temperatures of hundreds of degrees below zero.

Theoretical physicists in the early 1970s predicted that weakly interacting two-dimensional gases would exhibit similar behaviors under a variety of conditions as they neared the critical point of phase transition. Their prediction has remained unverified until now.

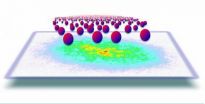

In their experiment, the UChicago researchers super-cooled thousands of cesium atoms to 10 nano-Kelvin, billionths of a degree above absolute zero (-459.67 degrees Fahrenheit), then loaded them into a pancake-like laser trap. The trap simulated a two-dimensional system by restricting the atoms' motion vertically but allowed a significant degree of horizontal freedom.

Chin's team was able to control the properties of this cold-atom gas system to make it non-interacting, weakly interacting or strongly interacting and then compared the results.

"At the same time, we can prepare the two-dimensional system at different sizes and also at different temperatures," Chin said. They could adjust the size parameters from 10 to 100 microns (a human hair is approximately 50 microns in diameter), and the temperature parameters from 10 to 100 nano-Kelvin.

Their experiment showed that no matter how they changed these three parameters, just one general description could characterize the resulting dynamics.

"There's a strong reason to believe that this kind of scale invariance can be extrapolated and on a more fundamental level can be mapped to other types of two-dimensional systems," Chin said. "The bigger question is whether our observation can shed light on other complex phenomena in nature. So our next step will be to explore going beyond two-dimensional systems."

INFORMATION:

Citation: "Observation of scale invariance and universality in two-dimensional Bose gases," by Chen-Lung Hung, Xibo Zhang, Nathan Gemelke, and Cheng Chin, Advance Online Publication, Nature, Vol. 469, No. 7333, Jan. 26, 2011.

Same rules apply to some experimental systems regardless of scale

2011-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rheumatoid arthritis researchers redefine remission

2011-02-04

ATLANTA – The American College of Rheumatology today announced the release of two new provisional definitions of rheumatoid arthritis remission, which are to be applied to future RA clinical trials.

According to research presented in the March issue of Arthritis & Rheumatism, a person with RA who is enrolled in a clinical trial would need to meet one of the following definitions to be considered in remission:

1. Tender joint count, swollen joint count (on 28 joint counts), C-reactive protein (in mg/dl), and patient global assessment scores (on a scale of zero to 10) ...

Microbiologists at TU Muenchen aim to optimize bio-ethanol production

2011-02-04

Food versus fuel -- this rivalry is gaining significance against a backdrop of increasingly scarce farmland and a concurrent trend towards the use of bio-fuels. Researchers at the Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM) are helping to resolve this rivalry: They are working to effectively utilize residual field crop material – which has been difficult to use thus far – for the industrial production of bio-ethanol. They took a closer look at bacteria that transform cellulose into sugar, thereby increasing the energy yield from plants utilized. If this approach works, both ...

New national study finds mountain bike-related injuries down 56 percent

2011-02-04

Mountain biking, also known as off-road biking, is a great way to stay physically active while enjoying nature and exploring the outdoors. The good news is that mountain biking-related injuries have decreased. A new study conducted by researchers at the Center for Injury Research and Policy of The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital found the number of mountain bike-related injuries decreased 56 percent over the 14-year study period (1994 to 2007) – going from a high of more than 23,000 injuries in 1995 to just over 10,000 injuries in 2007.

"The large ...

BU School of Public Health finds simple interventions reduce newborn deaths in Africa

2011-02-04

Training community birth attendants in rural Zambia in a simple newborn resuscitation protocol reduced neonatal deaths by nearly 50 percent – a finding that shows high potential to save lives in similar remote settings, a team of Boston University School of Public Health [BUSPH] international health researchers is reporting.

Findings published Feb. 3 in the BMJ by the team from the BU Center for Global Health and Development show that training and equipping Zambian traditional birth attendants to perform a neonatal resuscitation intervention led to a net reduction of ...

Analyzing long-term impacts of biofuel on the land

2011-02-04

Madison WI, FEBRUARY 03, 2011 – The growing development and implementation of renewable biofuel energy has considerable advantages over using declining supplies of fossil fuels. However, meeting the demands of a fuel-driven society may require utilizing all biofuel sources including agricultural crop residues.

While a useful biofuel source, crop residues also play a crucial role in maintaining soil organic carbon stock. This stock of organic carbon preserves soil functions and our global environment as well ensures the sustainable long-term production of biofuel feedstock.

In ...

New drought record from long-lived Mexican trees may illuminate fates of past civilizations

2011-02-04

WASHINGTON — A new, detailed record of rainfall fluctuations in ancient Mexico that spans more than twelve centuries promises to improve our understanding of the role drought played in the rise and fall of pre-Hispanic civilizations.

Prior evidence has indicated that droughts could have been key factors in the fates of major cultures in ancient Mexico and Central America (Mesoamerica). But there have been many gaps in the paleoclimate record, such as the exact timing and geographic extension of some seemingly influential dry spells.

The new, 1,238-year-long tree-ring ...

Helping feed the world without polluting its waters

2011-02-04

A growing global population has lead to increasing demands for food. Farmers around the world rely, at least in part on phosphorus-based fertilizers in order to sustain and improve crop yields. But the overuse of phosphorus can lead to freshwater pollution and the development of a host of problems, such as the spread of blue-green algae in lakes and the growth of coastal 'dead zones'.

A further issue is that phosphorus comes from phosphate rock, a non-renewable resource of which there are limited supplies in such geopolitically charged areas as Western Sahara and China.

Now, ...

New discoveries improve climate models

2011-02-04

New discoveries on how underwater ridges impact the ocean's circulation system will help improve climate projections.

An underwater ridge can trap the flow of cold, dense water at the bottom of the ocean. Without the ridge, deepwater can flow freely and speed up the ocean circulation pattern, which generally increases the flow of warm surface water.

Warm water on the ocean's surface makes the formation of sea ice difficult. With less ice present to reflect the sun, surface water will absorb more sunlight and continue to warm.

U.S. Geological Survey scientists looked ...

Coffee, energy drinkers beware: Many mega-sized drinks loaded with sugar, MU nutrition expert says

2011-02-04

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Starbucks recently announced a new-sized 31-ounce drink, the "Trenta," which will be in stores this spring. The mega-sized coffee joins the ranks of other energy drinks that can pack plenty of caffeine and calories. Ellen Schuster, a University of Missouri nutrition expert, says that Americans should be wary of extra calories and sugar in the quest for bigger, bolder drinks.

"The sheer size of new coffee and energy drinks increases consumers' potential for unhealthy calorie and sugar consumption," said Schuster, state specialist for MU Extension and the ...

New model by University of Nevada for how Nevada gold deposits formed may help in gold exploration

2011-02-04

RENO, Nev. – A team of University of Nevada, Reno and University of Nevada, Las Vegas researchers have devised a new model for how Nevada's gold deposits formed, which may help in exploration efforts for new gold deposits.

The deposits, known as Carlin-type gold deposits, are characterized by extremely fine-grained nanometer-sized particles of gold adhered to pyrite over large areas that can extend to great depths. More gold has been mined from Carlin-type deposits in Nevada in the last 50 years – more than $200 billion worth at today's gold prices – than was ever mined ...