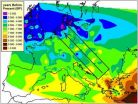

(Press-News.org) New research shows that the 2010 Amazon drought may have been even more devastating to the region's rainforests than the unusual 2005 drought, which was previously billed as a one-in-100 year event.

Analyses of rainfall across 5.3 million square kilometres of Amazonia during the 2010 dry season, published tomorrow in Science, shows that the drought was more widespread and severe than in 2005. The UK-Brazilian team also calculate that the carbon impact of the 2010 drought may eventually exceed the 5 billion tonnes of CO2 released following the 2005 event, as severe droughts kill rainforest trees. For context, the United States emitted 5.4 billion tonnes of CO2 from fossil fuel use in 2009.

The authors suggest that if extreme droughts like these become more frequent, the days of the Amazon rainforest acting as a natural buffer to man-made carbon emissions may be numbered.

Lead author Dr Simon Lewis, from the University of Leeds, said: "Having two events of this magnitude in such close succession is extremely unusual, but is unfortunately consistent with those climate models that project a grim future for Amazonia."

The Amazon rainforest covers an area approximately 25 times the size of the UK. University of Leeds scientists have previously shown that in a normal year intact forests absorb approximately 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 (1). This counter-balances the emissions from deforestation, logging and fire across the Amazon and has helped slow down climate change in recent decades.

In 2005, the region was struck by a rare drought which killed trees within the rainforest. On the ground monitoring showed that these forests stopped absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, and as the dead trees rotted they released CO2 to the atmosphere.

The unusual drought, affecting south-western Amazonia, was described by scientists at the time as a 'one-in-100-year event' (2), but just five years later the region was struck by a similar extreme drought that caused the Rio Negro tributary of the Amazon river to fall to its lowest level on record.

The new research, co-led by Dr Lewis and Brazilian scientist Dr Paulo Brando, used the known relationship between drought intensity in 2005 and tree deaths to estimate the impact of the 2010 drought.

They predict that Amazon forests will not absorb their usual 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere in both 2010 and 2011, and that a further 5 billion tonnes of CO2 will be released to the atmosphere over the coming years once the trees that are killed by the new drought rot.

Dr Brando, from Brazil's Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), said "We will not know exactly how many trees were killed until we can complete forest measurements on the ground.

"It could be that many of the drought susceptible trees were killed off in 2005, which would reduce the number killed last year. On the other hand, the first drought may have weakened a large number of trees so increasing the number dying in the 2010 dry season.

"Our results should be seen as an initial estimate. The emissions estimates do not include those from forest fires, which spread over extensive areas of the Amazon during hot and dry years. These fires release large amounts of carbon to the atmosphere."

Some global climate models suggest that Amazon droughts like these will become more frequent in future as a result of greenhouse gas emissions.

Dr Lewis added: "Two unusual and extreme droughts occurring within a decade may largely offset the carbon absorbed by intact Amazon forests during that time. If events like this happen more often, the Amazon rainforest would reach a point where it shifts from being a valuable carbon sink slowing climate change, to a major source of greenhouse gasses that could speed it up.

"Considerable uncertainty remains surrounding the impacts of climate change on the Amazon. This new research adds to a body of evidence suggesting that severe droughts will become more frequent leading to important consequences for Amazonian forests. If greenhouse gas emissions contribute to Amazon droughts that in turn cause forests to release carbon, this feedback loop would be extremely concerning. Put more starkly, current emissions pathways risk playing Russian roulette with the world's largest rainforest."

The research was a collaboration between the Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazonia (IPAM) in Brazil. The work was funded by the Royal Society, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the US National Science Foundation.

###

For more information

To request an interview with Dr Simon Lewis, please contact Hannah Isom in the University of Leeds press office on 0113 343 5764 or email h.isom@leeds.ac.uk.

The paper entitled 'The 2010 Amazon Drought' by Simon L Lewis, Paulo M Brando, Oliver L Phillips, Geertje MF van der Heijden and Daniel Nepstad is published in the journal Science on Friday 4 February 2011.

(1) Phillips, O. L. et al. Drought Sensitivity of the Amazon Rainforest, Science 323, 1344-1347 (2009).

(2) Marengo, J. A., et al. The Drought of Amazonia in 2005, Journal of Climate, 21, 495-516.

END

WALNUT CREEK, Calif.—A tiny crustacean that has been used for decades to develop and monitor environmental regulations is the first of its kind to have its genetic code sequenced and analyzed—revealing the most gene-packed animal characterized to date. The information deciphered could help researchers develop and conduct real-time monitoring systems of the effects of environmental remediation efforts.

Considered a keystone species in freshwater ecosystems, the waterflea, Daphnia pulex, is roughly the size of the equal sign on a keyboard. Its 200 million-base genome was ...

La Jolla, CA, February 2, 2011 – Embargoed by the journal Science until February 3, 2011, 2 PM, Eastern time - A team of scientists at The Scripps Research Institute has discovered a new way to stabilize proteins — the workhorse biological macromolecules found in all organisms. Proteins serve as the functional basis of many types of biologic drugs used to treat everything from arthritis, anemia, and diabetes to cancer.

As described in the February 4, 2011 edition of the journal Science, when the team attached a specific oligomeric array of sugars called a "glycan" to ...

In a discovery that may lead to a new treatment for breast cancer that has spread to the bone, a Princeton University research team has unraveled a mystery about how these tumors take root.

Cancer cells often travel throughout the body and cause new tumors in individuals with advanced breast cancer -- a process called metastasis -- commonly resulting in malignant bone tumors. What the Princeton research has uncovered is the exact mechanism that lets the traveling tumor cells disrupt normal bone growth. By zeroing in on the molecules involved, and particularly a protein ...

Australian scientists have successfully cleared a HIV-like infection from mice by boosting the function of cells vital to the immune response.

A team led by Dr Marc Pellegrini from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute showed that a cell signaling hormone called interleukin-7 (IL-7) reinvigorates the immune response to chronic viral infection, allowing the host to completely clear virus. Their findings were released in today's edition of the journal Cell.

Dr Pellegrini, from the institute's Infection and Immunity division, said the finding could lead to a cure for chronic ...

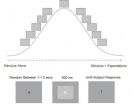

The human brain works incredibly fast. However, visual impressions are so complex that their processing takes several hundred milliseconds before they enter our consciousness. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt am Main have now shown that this delay may vary in length. When the brain possesses some prior information − that is, when it already knows what it is about to see − conscious recognition occurs faster. Until now, neuroscientists assumed that the processes leading up to conscious perception were rather rigid and that ...

One of the most significant socioeconomic changes in the history of humanity took place around 10,000 years ago, when the Near East went from an economy based on hunting and gathering (Mesolithic) to another kind on agriculture (Neolithic). Farmers rapidly entered the Balkan Peninsula and then advanced gradually throughout the rest of Europe.

Various theories have been proposed over recent years to explain this process, and now physicists from the University of Girona (UdG) have for the first time presented a new model to explain how the Neolithic front slowed down as ...

Massive Art Multimedia in Austria and CoSi Elektronik in Germany have a history of collaboration on successful technical projects. A brainstorming session between their developers produced the idea of bringing together many aspects of the modern computing world and applying them specifically to the one group in society that is least likely to already feel those benefits - senior citizens. As with so many projects of this nature, the funding for development was out of reach of two SMEs. By facilitating the funding process EUREKA permitted the development of the project now ...

Conservationists across the United States are racing to discover a solution to White-Nose Syndrome, a disease that is threatening to wipe out bat species across North America. A review published in Conservation Biology reveals that although WNS has already killed one million bats, there are critical knowledge gaps preventing researchers from combating the disease.

WNS is a fatal disease that targets hibernating bats and is believed to be caused by a newly discovered cold-adapted fungus, Geomyces destructans, which infects and invades the living skin of hibernating bats. ...

Using a generic drug to treat hypertension and heart failure, instead of branded medicines from the same class, could save the UK National Health Service (NHS) at least £200 million in 2011 without any real reduction in clinical benefits.

That is the key finding of a systematic review, statistical meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis just published online by IJCP, the International Journal of Clinical Practice.

Researchers from University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust looked at 14 hypertension and heart studies published between 1998 and 2009 ...

The genes that make up the human genome were mapped by HUGO, the Human Genome Organisation, and published in 2001. Now the project is expanding into the HUPO, the Human Proteome Organisation. Within the framework of this organisation, many hundreds of researchers around the world will work together to identify the proteins that the different genes give rise to in the human body.

"The 'proteome', the set of all human proteins, is significantly more complicated than the genome. There are over 20 000 proteins coded by the genome in the human body and each protein can have ...