(Press-News.org) New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

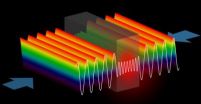

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light waves with the same frequency and amplitude that are in step with one another.

Last summer, Yale physicist A. Douglas Stone and his team published a study explaining the theory behind an anti-laser, demonstrating that such a device could be built using silicon, the most common semiconductor material. But it wasn't until now, after joining forces with the experimental group of his colleague Hui Cao, that the team actually built a functioning anti-laser, which they call a coherent perfect absorber (CPA).

The team, whose results appear in the Feb. 18 issue of the journal Science, focused two laser beams with a specific frequency into a cavity containing a silicon wafer that acted as a "loss medium." The wafer aligned the light waves in such a way that they became perfectly trapped, bouncing back and forth indefinitely until they were eventually absorbed and transformed into heat.

Stone believes that CPAs could one day be used as optical switches, detectors and other components in the next generation of computers, called optical computers, which will be powered by light in addition to electrons. Another application might be in radiology, where Stone said the principle of the CPA could be employed to target electromagnetic radiation to a small region within normally opaque human tissue, either for therapeutic or imaging purposes.

Theoretically, the CPA should be able to absorb 99.999 percent of the incoming light. Due to experimental limitations, the team's current CPA absorbs 99.4 percent. "But the CPA we built is just a proof of concept," Stone said. "I'm confident we will start to approach the theoretical limit as we build more sophisticated CPAs." Similarly, the team's first CPA is about one centimeter across at the moment, but Stone said that computer simulations have shown how to build one as small as six microns (about one-twentieth the width of an average human hair).

The team that built the CPA, led by Cao and another Yale physicist, Wenjie Wan, demonstrated the effect for near-infrared radiation, which is slightly "redder" than the eye can see and which is the frequency of light that the device naturally absorbs when ordinary silicon is used. But the team expects that, with some tinkering of the cavity and loss medium in future versions, the CPA will be able to absorb visible light as well as the specific infrared frequencies used in fiber optic communications.

It was while explaining the complex physics behind lasers to a visiting professor that Stone first came up with the idea of an anti-laser. When Stone suggested his colleague think about a laser working in reverse in order to help him understand how a conventional laser works, Stone began contemplating whether it was possible to actually build a laser that would work backwards, absorbing light at specific frequencies rather than emitting it.

"It went from being a useful thought experiment to having me wondering whether you could really do that," Stone said. "After some research, we found that several physicists had hinted at the concept in books and scientific papers, but no one had ever developed the idea."

INFORMATION:

Scientists build world's first anti-laser

2011-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The real avatar

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

Taking brain-computer interfaces to the next phase

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...

Skeleton regulates male fertility

2011-02-18

NEW YORK (February 17, 2011) – Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center have discovered that the skeleton acts as a regulator of fertility in male mice through a hormone released by bone, known as osteocalcin.

The research, led by Gerard Karsenty, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, is slated to appear online on February 17 in Cell, ahead of the journal's print edition, scheduled for March 4.

Until now, interactions between bone and the reproductive system have focused only on the influence ...

Put major government policy options through a science test first, biodiversity experts urge

2011-02-18

Scientific advice on the consequences of specific policy options confronting government decision makers is key to managing global biodiversity change.

That's the view of leading scientists anxiously anticipating the first meeting of a new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-like mechanism for biodiversity at which its workings and work program will be defined.

Writing in the journal Science, the scientists say the new mechanism, called the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), should adopt a modified working approach ...

Subtle shifts, not major sweeps, drove human evolution

2011-02-18

The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds.

Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species.

By examining the sequences of nearly ...

Dr. Todd Kuiken, pioneer of bionic arm control at RIC, to present latest advances at AAAS meeting

2011-02-18

VIDEO:

Glen Lehman discusses his research.

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON (February 17) –Todd Kuiken, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the Center for Bionic Medicine and Director of Amputee Services at The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), designated the "#1 Rehabilitation Hospital in America" by U.S. News & World Report since 1991, will present the latest in Targeted Muscle Reinnervation (TMR), a bionic limb technology, during the opening press briefing and ...

Policy experts say changes in expectations and funding key to genomic medicine's future

2011-02-18

INDIANAPOLIS – Unrealistic expectations about genomic medicine have created a "bubble" that needs deflating before it puts the field's long term benefits at risk, four policy experts write in the current issue of the journal Science.

Ten years after the deciphering of the human genetic code was accompanied by over-hyped promises of medical breakthroughs, it may be time to reevaluate funding priorities to better understand how to change behaviors and reap the health benefits that would result.

In addition, the authors say, scientists need to foster more realistic understanding ...

Scientists uncover surprising features of bear hibernation

2011-02-18

Fairbanks, ALASKA—Black bears show surprisingly large and previously unobserved decreases in their metabolism during and after hibernation according to a paper by scientists at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and published in the 18 February issue of the journal Science.

"In general, an animal's metabolism slows to about half for each 10 degree (Celsius) drop in body temperature. Black bears' metabolism slowed by 75 percent, but their core body temperature decreased by only five to six degrees," said Øivind Tøien, IAB research scientist ...

Flocculent spiral NGC 2841

2011-02-18

Star formation is one of the most important processes in shaping the Universe; it plays a pivotal role in the evolution of galaxies and it is also in the earliest stages of star formation that planetary systems first appear.

Yet there is still much that astronomers don't understand, such as how do the properties of stellar nurseries vary according to the composition and density of the gas present, and what triggers star formation in the first place? The driving force behind star formation is particularly unclear for a type of galaxy called a flocculent spiral, such as ...

Improving microscopy by following the astronomers' guide star

2011-02-18

A corrective strategy used by astronomers to sharpen images of celestial bodies can now help scientists see with more depth and clarity into the living brain of a mouse. Eric Betzig, a group leader at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Farm Research Campus, will present his team's latest work using adaptive optics for biology at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. during a press conference on Thursday, Feb., 17, and a panel discussion on Friday, Feb. 18.

A key problem in microscopy is that when ...