(Press-News.org) (MEMPHIS, Tenn. – March 9, 2011) Despite dramatically improved survival rates for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), relapse remains a leading cause of death from the disease. Work led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital investigators identified mutations in a gene named CREBBP that may help the cancer resist steroid treatment and fuel ALL's return.

CREBBP plays an important role in normal blood cell development, helping to switch other genes on and off. In this study, researchers found that 18.3 percent of the 71 relapsed-ALL patients carried alterations in the DNA sequence of CREBBP. In contrast, the gene's sequence was changed in just one of the 270 young leukemia patients whose cancer did not return.

Investigators say the gene is a potential indicator of relapse risk because of the high frequency of CREBBP mutations in relapsed patients and evidence the changes persisted from diagnosis or emerged at relapse from subpopulations of leukemia cells present from the beginning. Researchers also found evidence the changes occur in important regulatory regions of the gene and affect cell function, including how cancer cells respond to the steroids that play an important role in cancer treatment. The work appears in the March 10 issue of the scientific journal Nature.

"This study gives us further evidence that detailed genomic studies can identify important mutations that influence tumor response to treatment," said Charles Mullighan, M.D., Ph.D., assistant member of the St. Jude Department of Pathology. Mullighan and Jinghui Zhang, Ph.D., an associate member of the St. Jude Department of Computational Biology, are co-first authors. Mullighan is also the corresponding and senior author.

In the same issue of Nature, investigators also reported that deletions and deactivating mutations in CREBBP and a related gene known as EP300 occurred in about one-third of patients identified with one of the two most common subtypes of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mullighan is one of that study's five St. Jude co-authors.

Previous reports have linked deletions or chromosome rearrangements involving CREBBP to rare cases of acute leukemia. But this is the first study linking changes in the gene's DNA sequence to leukemia and lymphoma, cancers of the blood and bone marrow.

ALL is the most common childhood cancer. While ALL cure rates have climbed to 90 percent, the disease is often deadly if it returns. This study was designed to advance understanding of the biological basis of treatment failure. "The results of this study emphasize that there are additional genetic changes that help determine whether a child does well or relapses," Mullighan said.

The findings stem from the largest DNA sequencing project yet for ALL, which is diagnosed in about 3,000 U.S. children annually. Researchers from St. Jude and the National Cancer Institute tracked changes in 300 genes from 23 young ALL patients. For each gene, researchers compared the DNA makeup in the patient's normal cells with the sequence at diagnosis and relapse.

The effort turned up 52 non-inherited mutations in 32 genes, many for the first time. The group included four in CREBBP. When researchers checked another 341 young leukemia patients for alteration in CREBBP, they found that 13 of the 71 relapsed-ALL patients carried changes. In two more, pieces of CREBBP's DNA were deleted.

"The robust and accurate analytical method that we developed for processing such a large data volume made discovery of the CREBBP mutations possible," Zhang said. "This exciting finding illustrates that genomic sequencing can provide insight into not only disease initiation, but progression and prognosis as well."

Fourteen mutations were found scattered throughout CREBBP. The list includes an alteration also linked to Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, a rare inherited multisystem developmental disorder, as well as mutations linked to the cell's steroid response. Four alterations occurred in the region of the gene that regulates DNA expression through a process of chemical modification known as acetylation. Working in mouse cells growing in the laboratory, researchers showed that CREBBP mutations disrupted acetylation of key DNA targets.

When researchers treated CREBBP-mutated leukemia cells growing in the laboratory with the steroid dexamethasone, a majority showed resistance to the drug. The study included cells from nine ALL subtypes. But researchers found most of the cells proved sensitive to another drug. That drug, vorinostat, uses a different mechanism to impact acetylation. Researchers now plan to test vorinostat in a mouse model of relapsed ALL.

###

The other authors of this paper are Lawryn Kasper, Stephanie Lerach, Debbie Payne-Turner, Sue Heatley, Linda Holmfeldt, J. Racquel Collins-Underwood, Jing Ma, Ching-Hon Pui, Sharyn Baker, Paul Brindle and James Downing, all of St. Jude; Letha Phillips, formerly of St. Jude, and Kenneth Buetow, NCI Center for Bioinformatics and NCI Laboratory of Population Genetics.

The work was supported in part by supported in part by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant and ALSAC.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital is internationally recognized for its pioneering research and treatment of children with cancer and other catastrophic diseases. Ranked the No. 1 pediatric cancer hospital by Parents magazine and the No. 1 children's cancer hospital by U.S. News & World Report, St. Jude is the first and only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center devoted solely to children. St. Jude has treated children from all 50 states and from around the world, serving as a trusted resource for physicians and researchers. St. Jude has developed research protocols that helped push overall survival rates for childhood cancer from less than 20 percent when the hospital opened to almost 80 percent today. St. Jude is the national coordinating center for the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium and the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. In addition to pediatric cancer research, St. Jude is also a leader in sickle cell disease research and is a globally prominent research center for influenza.

Founded in 1962 by the late entertainer Danny Thomas, St. Jude freely shares its discoveries with scientific and medical communities around the world, publishing more research articles than any other pediatric cancer research center in the United States. St. Jude treats more than 5,700 patients each year and is the only pediatric cancer research center where families never pay for treatment not covered by insurance. St. Jude is financially supported by thousands of individual donors, organizations and corporations without which the hospital's work would not be possible. For more information, go to www.stjude.org.

When leukemia returns, gene that mediates response to key drug often mutated

The effort led by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists identified the gene as a potential marker of relapse risk and involved the most comprehensive search yet for genomic changes in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

2011-03-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gene variant influences chronic kidney disease risk

2011-03-10

A team of researchers from the United States and Europe has identified a single genetic mutation in the CUBN gene that is associated with albuminuria both with and without diabetes. Albuminuria is a condition caused by the leaking of the protein albumin into the urine, which is an indication of kidney disease.

The research team, known as the CKDGen Consortium, examined data from several genome-wide association studies to identify missense variant (I2984V) in the CUBN gene. The association between the CUBN variant and albuminuria was observed in 63,153 individuals with ...

New microscope decodes complex eye circuitry

2011-03-10

VIDEO:

Ganglion cells preferentially form synapses with those amacrine cells whose dendrites run in the direction opposite -- seen from the ganglion cell - to the preferred direction of motion (amacrine...

Click here for more information.

The sensory cells in the retina of the mammalian eye convert light stimuli into electrical signals and transmit them via downstream interneurons to the retinal ganglion cells which, in turn, forward them to the brain. The interneurons ...

Physicists measure current-induced torque in nonvolatile magnetic memory devices

2011-03-10

ITHACA, N.Y. - Tomorrow's nonvolatile memory devices – computer memory that can retain stored information even when not powered – will profoundly change electronics, and Cornell University researchers have discovered a new way of measuring and optimizing their performance.

Using a very fast oscilloscope, researchers led by Dan Ralph, the Horace White Professor of Physics, and Robert Buhrman, the J.E. Sweet Professor of Applied and Engineering Physics, have figured out how to quantify the strength of current-induced torques used to write information in memory devices ...

NASA and other satellites keeping busy with this week's severe weather

2011-03-10

Satellites have been busy this week covering severe weather across the U.S. Today, the GOES-13 satellite and NASA's Aqua satellite captured an image of the huge stretch of clouds associated with a huge and soggy cold front as it continues its slow march eastward. Earlier this week, NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite captured images of severe weather that generated tornadoes over Louisiana.

Today the eastern third of the U.S. is being buffered by a large storm that stretches from southeastern Minnesota east to Wisconsin and Michigan, then south through ...

International panel revises 'McDonald Criteria' for diagnosing multiple sclerosis

2011-03-10

International Panel Revises "McDonald Criteria" for Diagnosing MS -- Use of new data should speed diagnosis -- Publication coincides with MS Awareness Week

An international panel has revised and simplified the "McDonald Criteria" commonly used to diagnose multiple sclerosis, incorporating new data that should speed the diagnosis without compromising accuracy. The International Panel on Diagnosis of MS, organized and supported by the National MS Society and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, was chaired by Chris H. Polman, MD, PhD ...

MIT scientists identify new H1N1 mutation that could allow virus to spread more easily

2011-03-10

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- In the fall of 1917, a new strain of influenza swirled around the globe. At first, it resembled a typical flu epidemic: Most deaths occurred among the elderly, while younger people recovered quickly. However, in the summer of 1918, a deadlier version of the same virus began spreading, with disastrous consequence. In total, the pandemic killed at least 50 million people — about 3 percent of the world's population at the time.

That two-wave pattern is typical of pandemic flu viruses, which is why many scientists worry that the 2009 H1N1 ("swine") flu ...

New study proves the brain has 3 layers of working memory

2011-03-10

Researchers from Rice University and Georgia Institute of Technology have found support for the theory that the brain has three concentric layers of working memory where it stores readily available items. Memory researchers have long debated whether there are two or three layers and what the capacity and function of each layer is.

In a paper in the March issue of the Journal of Cognitive Psychology, researchers found that short-term memory is made up of three areas: a core focusing on one active item, a surrounding area holding at least three more active items, and a ...

Giving children the power to be scientists

2011-03-10

Children who are taught how to think and act like scientists develop a clearer understanding of the subject, a study has shown.

The research project led by The University of Nottingham and The Open University has shown that school children who took the lead in investigating science topics of interest to them gained an understanding of good scientific practice.

The study shows that this method of 'personal inquiry' could be used to help children develop the skills needed to weigh up misinformation in the media, understand the impact of science and technology on everyday ...

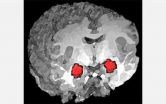

Researchers selectively control anxiety pathways in the brain

2011-03-10

A new study sheds light--both literally and figuratively--on the intricate brain cell connections responsible for anxiety.

Scientists at Stanford University recently used light to activate mouse neurons and precisely identify neural circuits that increase or decrease anxiety-related behaviors. Pinpointing the origin of anxiety brings psychiatric professionals closer to understanding anxiety disorders, the most common class of psychiatric disease.

A research team led by Karl Deisseroth, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and bioengineering, identified ...

Researchers develop synthetic compound that may lead to drugs to fight pancreatic, lung cancer

2011-03-10

DALLAS – March 10, 2011 – Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have identified a chemical compound that may eventually lead to a drug that fights cancers that are dependent on a particular anti-viral enzyme for growth.

The researchers are testing the compound's effectiveness at fighting tumors in mice. If it is successful, they will then work to develop a drug based on the compound to combat pancreatic and non-small cell lung cancer, two cancer types in which this particular enzyme, TBK-1, often is required for cancer cell survival.

"Our prediction is that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

Frontiers in Science Deep Dive webinar series: How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

UMaine researcher develops model to protect freshwater fish worldwide from extinction

Illinois and UChicago physicists develop a new method to measure the expansion rate of the universe

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

AI-powered platform accelerates discovery of new mRNA delivery materials

Quantum effect could power the next generation of battery-free devices

New research finds heart health benefits in combining mango and avocado daily

New research finds peanut butter consumption builds muscle power in older adults

Study identifies aging-associated mitochondrial circular RNAs

The brain’s primitive ‘fear center’ is actually a sophisticated mediator

Brain Healthy Campus Collaborative announces winner of first-ever Brain Health Prize

Tokyo Bay’s night lights reveal hidden boundaries between species

As worms and jellyfish wriggle, new AI tools track their neurons

[Press-News.org] When leukemia returns, gene that mediates response to key drug often mutatedThe effort led by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists identified the gene as a potential marker of relapse risk and involved the most comprehensive search yet for genomic changes in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia