(Press-News.org) RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Molecular machines can be found everywhere in nature, for example, transporting proteins through cells and aiding metabolism. To develop artificial molecular machines, scientists need to understand the rules that govern mechanics at the molecular or nanometer scale (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter).

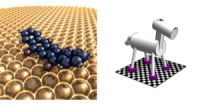

To address this challenge, a research team at the University of California, Riverside studied a class of molecular machines that 'walk' across a flat metal surface. They considered both bipedal machines that walk on two 'legs' and quadrupedal ones that walk on four.

"We made a horse-like structure with four 'hooves' to study how molecular machinery can organize the motion of multiple parts," said Ludwig Bartels, a professor of chemistry, whose lab led the research. "A couple of years ago, we discovered how we can transport carbon dioxide molecules along a straight line across a surface using a molecular machine with two 'feet' that moved one step at a time. For the new research, we wanted to create a species that can carry more cargo – which means it would need more legs. But if a species has more than two legs, how will it organize their motion?"

Bartels and colleagues performed experiments in the lab and found that the quadrupedal molecules use a pacing gait – both legs on one side of the molecule move together, followed next by the two legs on the opposite side of the molecule. The species they created moved reliably along a line, not rotating to the side or veering off course. The researchers also simulated a trotting of the species, in which diagonally opposite hooves move together, and found that this form of movement distorted the species far too much to be viable.

Having established how the molecule moves, the researchers next addressed a fundamental question about molecular machinery: Does a molecule – or portions of it – simply tunnel through barriers presented by the roughness it encounters along its path?

"If it did, this would be a fundamental departure from mechanics in the macroscopic world and would greatly speed up movement," Bartels said. "It would be like driving on a bumpy road with the wheels of your car going through the bumps rather than over them. Quantum-mechanics is known to allow such behavior for very light particles like electrons and hydrogen atoms, but would it also be relevant for big molecules?"

Bartels and colleagues varied the temperature in their experiments to provide the molecular machines with different levels of energy, and studied how the speed of the machines varied as a consequence. They found that a machine with two legs can use tunneling to zip through the surface corrugation. But a machine with four (or potentially more) legs is not able to employ tunneling; while such a machine can coordinate the movement of its hooves in pacing, it cannot coordinate their tunneling, the researchers found.

"Thus, even at the tiniest scale, if you want to transport cargo fast, you need a light and nimble bipedal vehicle," Bartels said. "Larger vehicles may be able to carry more cargo, but because they cannot use tunneling effectively, they end up having to move slowly. Is this discouraging? Not really, because molecular machinery as a concept is still in its infancy. Indeed, there is an advantage to having a molecule move slowly because it allows us to observe its movements more closely and learn how to control them."

Study results appeared online last week in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, and will appear in print in an upcoming issue of the journal.

Next, the researchers plan to develop molecular machines whose motion can be controlled by light.

Currently, molecular machines are being studied intensely for their functions in biology and for their therapeutic value. For example, patients with GERD (Gastroesophageal reflux disease) are prescribed proton pump inhibitors, which slow the pumping action of biological molecular machines, thus reducing stomach acid levels.

"Generally, scientists' picture of the working of such biological molecular machinery completely disregards tunneling," Bartels said. "Our study corrects this perception, which may, in turn, lead to novel ways of controlling or correcting the behavior of biological molecular machines."

Artificial molecular machines are of interest to the microelectronic industry in its quest for smaller and smaller active elements in computers and for data storage. Artificial molecular machines potentially can also operate inside cells like their biological counterparts, greatly benefiting medicine.

Bartels's lab used the following molecules in the study: anthraquinone and pentaquinone (both bipedal); and pentacenetetrone and dimethyl pentacenetetrone (both quadrupedal).

INFORMATION:

The research was made possible by dedicated instrumentation developed and built in the Bartels lab. Bartels specializes in developing scanning tunneling microscopy instrumentation and applying it to molecular systems. Besides the Department of Chemistry, he holds appointments in the departments of physics, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and the program in materials science and engineering.

He was joined in the study by the following researchers at UCR: postdoctoral scholar Zhihai Cheng; undergraduate student Eric S. Chu; graduate students Dezheng Sun, Daeho Kim, Yeming Zhu, MiaoMiao Luo, Greg Pawin, Kin L. Wong, Ki-Young Kwon and Robert Carp; and Michael Marsella, an associate professor of chemistry. Carp, who works in Marsella's lab, made dimethyl pentacenetetrone; the other chemicals used in the study are commercially available.

The research was supported by a Department of Energy grant to Bartels and a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to Bartels and Marsella. The latter grant was rated in a recent review of the NSF Division of Chemistry as "an exemplar of excellence in support of the Division's investment in research, education, and infrastructure."

The University of California, Riverside (www.ucr.edu) is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment of about 18,000 is expected to grow to 21,000 students by 2020. The campus is planning a medical school and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Graduate Center. The campus has an annual statewide economic impact of more than $1 billion.

A broadcast studio with fiber cable to the AT&T Hollywood hub is available for live or taped interviews. To learn more, call (951) UCR-NEWS.

Would a molecular horse trot, pace or glide across a surface?

UC Riverside chemists study quadrupedal molecular machines to provide an answer

2010-09-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New pathway identified in Parkinson's through brain imaging

2010-09-13

(NEW YORK, NY, September 13, 2010) – A new study led by researchers at Columbia University Medical Center has identified a novel molecular pathway underlying Parkinson's disease and points to existing drugs which may be able to slow progression of the disease.

The pathway involved proteins – known as polyamines – that were found to be responsible for the increase in build-up of other toxic proteins in neurons, which causes the neurons to malfunction and, eventually, die. Though high levels of polyamines have been found previously in patients with Parkinson's, the new ...

Wives as the new breadwinners

2010-09-13

Durham, NH—September 13, 2010— During the recent recession in the United States, many industries suffered significant layoffs, leaving individuals and families to revise their spending and rethink income opportunities. Many wives are increasingly becoming primary breadwinners or entering the labor market. A new article in Family Relations tests "the added worker" theory, which suggests wives who are not working may seek work as a substitute for husband's labor if he becomes unemployed, and finds that during a time of economic downturn wives are more likely to enter the ...

Making cookies that are good for your heart

2010-09-13

VIDEO:

Years of research has proven that saturated and trans fats clog arteries, make it tough for the heart to pump and are not valuable components of any diet. Unfortunately, they...

Click here for more information.

COLUMBIA, Mo. ¬— Years of research has proven that saturated and trans fats clog arteries, make it tough for the heart to pump and are not valuable components of any diet. Unfortunately, they are contained in many foods. Now, a University of Missouri research ...

Obama administration responds to call to action from Concordia researchers

2010-09-13

Montreal / September 13, 2010 – September 21, 2010 marks the one year anniversary of the release of a landmark document produced by researchers at Concordia University. Mobilizing The Will to Intervene (W2I) offers governments practical steps to prevent future genocides and mass atrocities. Produced by researchers with the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS) based at Concordia, the document was presented to the governments of Canada and The United States of America. It has already yielded concrete results.

Under President Barack Obama's leadership, ...

Latent HIV infection focus of NIDA's 2010 Avant-Garde Award

2010-09-13

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, announced today that Dr. Eric M. Verdin of the J. David Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, Calif., has been selected as the 2010 recipient of the NIDA Avant-Garde Award for HIV/AIDS Research for his proposal to study the mechanisms of latent HIV infection. NIDA's annual Avant-Garde award competition, now in its third year, is intended to stimulate high-impact research that may lead to groundbreaking opportunities for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS in drug abusers. Awardees ...

New study reconciles conflicting data on mental aging

2010-09-13

WASHINGTON — A new look at tests of mental aging reveals a good news-bad news situation. The bad news is all mental abilities appear to decline with age, to varying degrees. The good news is the drops are not as steep as some research showed, according to a study published by the American Psychological Association.

"There is now convincing evidence that even vocabulary knowledge and what's called crystallized intelligence decline at older ages," said study author Timothy Salthouse, PhD.

Longitudinal test scores look good in part because repeat test-takers grow familiar ...

Scientists glimpse dance of skeletons inside neurons

2010-09-13

Scientists at Emory University School of Medicine have uncovered how a structural component inside neurons performs two coordinated dance moves when the connections between neurons are strengthened.

The results are published online in the journal Nature Neuroscience, and will appear in a future print issue.

In experiments with neurons in culture, the researchers can distinguish two separate steps during long-term potentiation, an enhancement of communication between neurons thought to lie behind learning and memory. Both steps involve the remodeling of the internal ...

CU-Boulder study sheds light on how our brains get tripped up when we're anxious

2010-09-13

A new University of Colorado at Boulder study sheds light on the brain mechanisms that allow us to make choices and ultimately could be helpful in improving treatments for the millions of people who suffer from the effects of anxiety disorders.

In the study, CU-Boulder psychology Professor Yuko Munakata and her research colleagues found that "neural inhibition," a process that occurs when one nerve cell suppresses activity in another, is a critical aspect in our ability to make choices.

"The breakthrough here is that this helps us clarify the question of what is happening ...

Energy Express focus issue: Thin-film photovoltaic materials and devices

2010-09-13

WASHINGTON, September 13 – Developing renewable energy sources has never been more important, and solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies show great potential in this field. They convert direct sunlight into electricity with little impact on the environment. This field is constantly advancing, developing technologies that can convert power more efficiently and at a lower cost. To highlight breakthroughs in this area, the editors of Energy Express, a bi-monthly supplement to Optics Express, the open-access journal of the Optical Society (OSA), today published a special Focus ...

Over-the-top grass control in sorghum on the horizon

2010-09-13

AMARILLO - Apply today's chemicals to a sorghum crop for grass control and the sorghum will be killed off also. But a solution could be only a few years away if Texas AgriLife Research plots are any indication.

Dr. Brent Bean, AgriLife Research and Texas AgriLife Extension Service agronomist, has test plots that demonstrate sorghum hybrids tolerant to herbicides typically associated with grass control.

The control is needed not only for annual grass control but also for Johnsongrass, Bean said. Because Johnsongrass is closely related to grain sorghum, herbicides typically ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Would a molecular horse trot, pace or glide across a surface?UC Riverside chemists study quadrupedal molecular machines to provide an answer