(Press-News.org) The human eye long ago solved a problem common to both digital and film cameras: how to get good contrast in an image while also capturing faint detail. Nearly 50 years ago, physiologists described the retina's tricks for improving contrast and sharpening edges, but new experiments by neurobiologists at University of California, Berkeley and the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha show how the eye achieves this without sacrificing shadow detail. These details will be published next week in the online, open access journal PLoS Biology.

"Lateral inhibition" (when light-sensitive nerve cells in the retina inhibit dozens of their near neighbors) was first observed in horseshoe crabs by physiologist H. Keffer Hartline. This form of negative feedback was later shown to take place in the vertebrate eye, including the human eye, and has since been found in many sensory systems as a way to sharpen the discrimination of pitch or touch. Lateral inhibition fails, however, to account for the eye's ability to detect faint detail near edges, including the fact that we can see small, faint spots which ought to be invisible if their detection is inhibited by encircling retinal cells.

The retina in vertebrates is lined with a sheet of photoreceptor cells: the cones for day vision and the rods for night vision. The lens of the eye focuses images onto this sheet, and like the pixels in a digital camera, each photoreceptor generates an electrical response proportional to the intensity of the light falling on it. The signal releases a chemical neurotransmitter (glutamate) that affects neurons downstream, ultimately reaching the brain. Unlike the pixels of a digital camera, however, photoreceptors affect the photoreceptors around them through so-called horizontal cells, which underlie and touch as many as 100 individual photoreceptors. The horizontal cells integrate signals from all these photoreceptors and provide broad inhibitory feedback. This feedback is thought to underlie lateral inhibition.

In the current study, Richard Kramer and former graduate student Skyler L. Jackman discovered that during lateral inhibition, horizontal cells not only inhibit their neighbors (negative feedback), but also boost the response of the nearest cells (positive feedback). That extra boost preserves the information in individual light detecting cells the rods and cones thereby retaining faint detail while accentuating edges. By locally offsetting negative feedback, positive feedback boosts the photoreceptor signal while preserving contrast enhancement. Positive feedback is local, whereas negative feedback extends laterally, enhancing contrast between center and surround.

The researchers also found that the two types of feedback work by different mechanisms. Traditional negative feedback uses electrical signals that propagate from horizontal cells to many nearby photoreceptors. The positive feedback, however, involves chemical signaling. When a horizontal cell receives glutamate from a photoreceptor, calcium ions flow into the horizontal cell. These ions trigger the horizontal cell to "talk back" to the photoreceptor, Kramer said. Because calcium doesn't spread very far within the horizontal cell, the positive feedback signal stays local, affecting only one or two nearby photoreceptors.

Jackman and Kramer found the same positive feedback in the cones of a zebrafish, lizard, salamander, anole (whose retina contains only cones) and rabbit, proving that "this is not just some weird thing that happens in lizards; it seems to be true across all vertebrates and presumably humans."

###

Coauthors with Kramer and Jackman are Norbert Babai and Wallace B. Thoreson of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and James J. Chambers of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health EY015514 and EY018957 (RHK), EY10542 (WBT), Research to Prevent Blindness (WBT), and the Human Frontiers Science Program (JCC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests statement: The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Why the eye is better than a camera

2011-05-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Nicotine and cocaine leave similar mark on brain after first contact

2011-05-04

The effects of nicotine upon brain regions involved in addiction mirror those of cocaine, according to new neuroscience research.

A single 15-minute exposure to nicotine caused a long-term increase in the excitability of neurons involved in reward, according to a study published in The Journal of Neuroscience. The results suggest that nicotine and cocaine hijack similar mechanisms of memory on first contact to create long-lasting changes in a person's brain.

"Of course, for smoking it's a very long-term behavioral change, but everything starts from the first exposure," ...

World's smallest atomic clock on sale

2011-05-04

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — A matchbook-sized atomic clock 100 times smaller than its commercial predecessors has been created by a team of researchers at Symmetricom Inc. Draper Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories. The portable Chip Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC) — only about 1.5 inches on a side and less than a half-inch in depth — also requires 100 times less power than its predecessors. Instead of 10 watts, it uses only 100 milliwatts.

"It's the difference between lugging around a device powered by a car battery and one powered by two AA batteries," said Sandia lead investigator ...

'Fatting in': Immigrant groups eat high-calorie American meals to fit in

2011-05-04

Immigrants to the United States and their U.S.-born children gain more than a new life and new citizenship. They gain weight. The wide availability of cheap, convenient, fatty American foods and large meal portions have been blamed for immigrants packing on pounds, approaching U.S. levels of obesity within 15 years of their move.

Psychologists show that it's not simply the abundance of high-calorie American junk food that causes weight gain. Instead, members of U.S. immigrant groups choose typical American dishes as a way to show that they belong and to prove their American-ness. ...

Scientists track evolution and spread of deadly fungus, one of the world's major killers

2011-05-04

New research has shed light on the origins of a fungal infection which is one of the major causes of death from AIDS-related illnesses. The study, published today in the journal PLoS Pathogens, funded by the Wellcome Trust and the BBSRC, shows how the more virulent forms of Cryptococcus neoformans evolved and spread out of Africa and into Asia.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a species of often highly aggressive fungi. One particular strain of the fungus – known as Cryptococcus neoformas variety grubii (Cng) – causes meningitis amongst patients with compromised immune systems ...

Ranking research

2011-05-04

A new approach to evaluating research papers exploits social bookmarking tools to extract relevance. Details are reported in the latest issue of the International Journal of Internet Technology and Secured Transactions.

Social bookmarking systems are almost indispensible. Very few of us do not use at least one system whether it's Delicious, Connotea, Trunk.ly, Reddit or any of countless others. For Academics and researchers CiteULike is one of the most popular and has been around since November 2004. CiteUlike [[http://www.CiteULike.org]] allows users to bookmark references ...

HIV drug could prevent cervical cancer

2011-05-04

A widely used HIV drug could be used to prevent cervical cancer caused by infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV), say scientists.

University of Manchester researchers, working with colleagues in Canada, have discovered how the antiviral drug lopinavir attacks HPV by switching on a natural viral defence system in infected cells.

The study, published in the journal Antiviral Therapy, builds on the team's previous work in 2006 that first identified lopinavir as a potential therapeutic for HPV-related cervical cancer following laboratory tests on cell cultures.

"Since ...

Early history of genetics revised

2011-05-04

The early history of genetics has to be re-written in the light of new findings. Scientists from the University Jena (Germany) in co-operation with colleagues from Prague found out that the traditional history of the 'rediscovery' of Gregor Johann Mendel's laws of heredity in 1900 has to be adjusted and some facets have to be added.

It all began in the year of 1865: Mendel, today known as the 'father of genetics', published his scientific findings about the cross breeding experiments of peas, that went largely unnoticed during his lifetime. His research notes and manuscripts ...

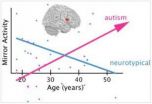

The mirror neuron system in autism: Broken or just slowly developing?

2011-05-04

Philadelphia, PA – 3 May 2011 – Developmental abnormalities in the mirror neuron system may contribute to social deficits in autism.

The mirror neuron system is a brain circuit that enables us to better understand and anticipate the actions of others. These circuits activate in similar ways when we perform actions or watch other people perform the same actions.

Now, a new study published in Biological Psychiatry reports that the mirror system in individuals with autism is not actually broken, but simply delayed.

Dr. Christian Keysers, lead author on the project, detailed ...

Amygdala detects spontaneity in human behavior

2011-05-04

A pianist is playing an unknown melody freely without reading from a musical score. How does the listener's brain recognise if this melody is improvised or if it is memorized? Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig investigated jazz musicians to discover which brain areas are especially sensitive to features of improvised behaviour. Among these are the amygdala and a network of areas known to be involved in the mental simulation of behaviour. Furthermore, the ability to correctly recognise improvisations was not only related ...

Hebrew University researchers demonstrate why DNA breaks down in cancer cells

2011-05-04

Jerusalem, May 3, 2011 – Damage to normal DNA is a hallmark of cancer cells. Although it had previously been known that damage to normal cells is caused by stress to their DNA replication when cancerous cells invade, the molecular basis for this remained unclear.

Now, for the first time, researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have shown that in early cancer development, cells suffer from insufficient building blocks to support normal DNA replication. It is possible to halt this by externally supplying the "building blocks," resulting in reduced DNA damage ...