(Press-News.org) WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - One of the world's most destructive wheat pathogens is genetically built to evade detection before infecting its host, according to a study that mapped the genome of the fungus.

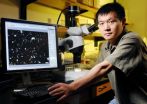

Stephen Goodwin, a Purdue and U.S. Department of Agriculture research plant pathologist, was the principal author on the effort to sequence the genome of the fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola, which causes septoria tritici blotch, a disease that greatly reduces yield and quality in wheat. Surprisingly, Goodwin said, the fungus had fewer genes related to production of enzymes that many other fungi use to penetrate and digest surfaces of plants while infecting them.

"We're guessing that the low number of enzymes is to avoid detection by plant defenses," said Goodwin, whose findings were published in the early online edition of the journal PLoS Genetics.

Enzymes often break down plant cell walls and begin removing nutrients, leading to the plant's death. M. graminicola, however, enters the plant through stomata, small pores in the surface of leaves that allow for exchange of gases and water.

Goodwin said the fungus seems to lay dormant between plant cells, avoiding detection. It later infects the plant, removing necessary nutrients and causing disease.

With the sequenced genome, scientists hope to discover which genes cause toxicity in wheat and determine ways to eliminate that toxicity or improve wheat's defenses against the fungus. Septoria tritici blotch is the No. 1 wheat pathogen in parts of Europe and is probably third in the United States, Goodwin said.

The genome also showed that M. graminicola has eight disposable chromosomes that seem to have no function. Goodwin said that plants with dispensable chromosomes have clear mechanisms for their maintenance, but no such mechanisms were obvious in the fungus.

Goodwin said the extra chromosomes were probably obtained from another species more than 10,000 years ago and have likely been retained for an important function, but it's not clear what that function is.

"That's a long time for these chromosomes to be maintained without an obvious function," he said. "They must be doing something important. Finding out what that is will be a key area for future research."

###Goodwin collaborated with 57 scientists from 24 other institutions. The U.S. Department of Energy's Joint Genome Institute and Plant Research International of The Netherlands were equal partners in the research.

Abstract on the research in this release is available at: http://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/research/2011/110613GoodwinGenome.html

Genome offers clue to functions of destructive wheat fungus

2011-06-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A scientific breakthrough at the IRCM could help understand certain cancers

2011-06-14

Montréal, June 13, 2011 – A scientific breakthrough by researchers at the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) will be published tomorrow in Developmental Cell, a scientific journal of the Cell Press group. Led by Dr. Frédéric Charron, the team of scientists discovered a new requirement for the proper functioning of the Sonic Hedgehog protein.

Sonic Hedgehog belongs to a family of proteins that gives cells the information needed for the embryo to develop properly. It plays a critical role in the development of many of the body's organs, such as the central ...

Under pressure, sodium, hydrogen could undergo a metamorphosis, emerging as superconductor

2011-06-14

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- In the search for superconductors, finding ways to compress hydrogen into a metal has been a point of focus ever since scientists predicted many years ago that electricity would flow, uninhibited, through such a material.

Liquid metallic hydrogen is thought to exist in the high-gravity interiors of Jupiter and Saturn. But so far, on Earth, researchers have been unable to use static compression techniques to squeeze hydrogen under high enough pressures to convert it into a metal. Shock-wave methods have been successful, but as experiments with diamond ...

Scientists find deadly amphibian disease in the last disease-free region of central America

2011-06-14

Smithsonian scientists have confirmed that chytridiomycosis, a rapidly spreading amphibian disease, has reached a site near Panama's Darien region. This was the last area in the entire mountainous neotropics to be free of the disease. This is troubling news for the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, a consortium of nine U.S. and Panamanian institutions that aims to rescue 20 species of frogs in imminent danger of extinction.

Chytridiomycosis has been linked to dramatic population declines or even extinctions of amphibian species worldwide. Within five ...

New study supports Darwin's hypothesis on competition between species

2011-06-14

A new study provides support for Darwin's hypothesis that the struggle for existence is stronger between more closely related species than those distantly related. While ecologists generally accept the premise, this new study contains the strongest direct experimental evidence yet to support its validity.

"We found that species extinction occurred more frequently and more rapidly between species of microorganisms that were more closely related, providing strong support for Darwin's theory, which we call the phylogenetic limiting similarity hypothesis," said Lin Jiang, ...

Sleep can boost classroom performance of college students

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Sleep can help college students retain and integrate new information to solve problems on a classroom exam, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that performance by university undergraduates on a microeconomics test was preserved after a 12-hour period that included sleep, especially for cognitively-taxing integration problems. In contrast, performance declined after 12 hours of wakefulness ...

College students sleep longer but drink more and get lower grades when classes start later

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Although a class schedule with later start times allows colleges students to get more sleep, it also gives them more time to stay out drinking at night. As a result, their grades are more likely to suffer, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that later class start times were associated with a delayed sleep schedule, which led to poorer sleep, more daytime sleepiness, and a lower grade-point ...

Sleep problems may be a link between perceived racism and poor health

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Perceived racial discrimination is associated with an increased risk of sleep disturbance, which may have a negative impact on mental and physical health, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that perceived racism was associated with an elevated risk of self-reported sleep disturbance, which was increased by 61 percent after adjusting for socioeconomic factors and symptoms of depression. ...

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia can reduce suicidal ideation

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Treating sleep problems with cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia can reduce suicidal ideation, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that about 21 percent of participants with insomnia (65 of 303) reported having suicidal thoughts or wishes during the past two weeks. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia produced a statistically significant post-treatment reduction in suicidal ...

White adolescent girls may be losing sleep from the pressure to be thin

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Sleep duration has a significant association with feelings of external pressure to obtain or maintain a thin body among adolescent girls, especially those who are white, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that pressures to have a thin body from girlfriends and from the media significantly predict sleep duration and account for 4.5 percent of the variance in hours of sleep for adolescent ...

Sleep loss in early childhood may contribute to the development of ADHD symptoms

2011-06-14

DARIEN, IL – Short sleep duration may contribute to the development or worsening of hyperactivity and inattention during early childhood, suggests a research abstract that will be presented Tuesday, June 14, in Minneapolis, Minn., at SLEEP 2011, the 25th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies LLC (APSS).

Results show that less sleep in preschool-age children significantly predicted worse parent-reported hyperactivity and inattention at kindergarten. In contrast, hyperactivity and inattention at preschool did not predict sleep duration at kindergarten. ...