(Press-News.org) National Institutes of Health researchers have identified a new pathway that sets the clock for programmed aging in normal cells. The study provides insights about the interaction between a toxic protein called progerin and telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes like aglets, the plastic tips that bind the ends of shoelaces.

The study by researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) appears in the June 13, 2011 early online edition of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Telomeres wear away during cell division. When they degrade sufficiently, the cell stops dividing and dies. The researchers have found that short or dysfunctional telomeres activate production of progerin, which is associated with age-related cell damage. As the telomeres shorten, the cell produces more progerin.

Progerin is a mutated version of a normal cellular protein called lamin A, which is encoded by the normal LMNA gene. Lamin A helps to maintain the normal structure of a cell's nucleus, the cellular repository of genetic information.

In 2003, NHGRI researchers discovered that a mutation in LMNA causes the rare premature aging condition, progeria, formally known as known as Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Progeria is an extremely rare disease in which children experience symptoms normally associated with advanced age, including hair loss, diminished subcutaneous fat, premature atherosclerosis and skeletal abnormalities. These children typically die from cardiovascular complications in their teens.

"Connecting this rare disease phenomenon and normal aging is bearing fruit in an important way," said NIH Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D., a senior author of the current paper. "This study highlights that valuable biological insights are gained by studying rare genetic disorders such as progeria. Our sense from the start was that progeria had a lot to teach us about the normal aging process and clues about more general biochemical and molecular mechanisms."

Collins led the earlier discovery of the gene mutation responsible for progeria and subsequent advances at NIH in understanding the biochemical and molecular underpinnings of the disease.

In a 2007 study, NIH researchers showed that normal cells of healthy people can produce a small amount of progerin, the toxic protein, even when they do not carry the mutation. The more cell divisions the cell underwent, the shorter the telomeres and the greater the production of progerin. But a mystery remained: What was triggering the production of the toxic progerin protein?

The current study shows that the mutation that causes progeria strongly activates the splicing of lamin A to produce the toxic progerin protein, leading to all of the features of premature aging suffered by children with this disease. But modifications in the splicing of LMNA are also at play in the presence of the normal gene.

The research suggests that the shortening of telomeres during normal cell division in individuals with normal LMNA genes somehow alters the way a normal cell processes genetic information when turning it into a protein, a process called RNA splicing. To build proteins, RNA is transcribed from genetic instructions embedded in DNA. RNA does not carry all of the linear information embedded in the ribbon of DNA; rather, the cell splices together segments of genetic information called exons that contain the code for building proteins, and removes the intervening letters of unused genetic information called introns. This mechanism appears to be altered by telomere shortening, and affects protein production for multiple proteins that are important for cytoskeleton integrity. Most importantly, this alteration in RNA splicing affects the processing of the LMNA messenger RNA, leading to an accumulation of the toxic progerin protein.

Cells age as part of the normal cell cycle process called senescence, which progressively advances through a limited number of divisions in the cell lifetime. "Telomere shortening during cellular senescence plays a causative role in activating progerin production and leads to extensive change in alternative splicing in multiple other genes," said lead author Kan Cao, Ph.D., an assistant professor of cell biology and molecular genetics at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Telomerase is an enzyme that can extend the structure of telomeres so that cells continue to maintain the ability to divide. The study supplied support for the telomere-progerin link, showing that cells that have a perpetual supply of telomerase, known as immortalized cells, produce very little progerin RNA. Most cells of this kind are cancer cells, which do not reach a normal cell cycle end point, and instead replicate out of control.

The researchers also conducted laboratory tests on normal cells from healthy individuals using biochemical markers to indicate the occurrence of progerin-generating RNA splicing in cells. The cell donors ranged in age from 10 to 92 years. Regardless of age, cells that passed through many cell cycles had progressively higher progerin production. Normal cells that produce higher concentrations of progerin also displayed shortened and dysfunctional telomeres, the tell-tale indication of many cell divisions.

In addition to their focus on progerin, the researchers conducted the first systematic analysis across the genome of alternative splicing during cellular aging, considering which other protein products are affected by jumbled instructions as RNA molecules assemble proteins through splicing. Using laboratory techniques that analyze the order of chemical units of RNA, called nucleotides, the researchers found that splicing is altered by short telomeres, affecting lamin A and a number of other genes, including those that encode proteins that play a role in the structure of the cell.

The researchers suggest that the combination of telomere fraying and loss with progerin production together induces cell aging. This finding lends insights into how progerin may participate in the normal aging process.

###

For more about Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, go to http://www.genome.gov/11007255.

NHGRI is one of the 27 institutes and centers at the NIH, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The NHGRI Division of Intramural Research develops and implements technology to understand, diagnose and treat genomic and genetic diseases. Additional information about NHGRI can be found at its website, www.genome.gov.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) - The Nation's Medical Research Agency - includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH researchers find new clues about aging

Genetic splicing mechanism triggers both premature aging syndrome and normal cellular aging

2011-06-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sniffing out a new source of stem cells

2011-06-14

A team of researchers, led by Emmanuel Nivet, now at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, has generated data in mice that suggest that adult stem cells from immune system tissue in the smell-sensing region of the human nose (human olfactory ecto–mesenchymal stem cells [OE-MSCs]) could provide a source of cells to treat brain disorders in which nerve cells are lost or irreparably damaged.

Stem cells are considered by many to be promising candidate sources of cells for the regeneration and repair of tissues damaged by various brain disorders (including traumatic ...

JCI online early table of contents: June 13, 2011

2011-06-14

EDITOR'S PICK: Sniffing out a new source of stem cells

A team of researchers, led by Emmanuel Nivet, now at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, has generated data in mice that suggest that adult stem cells from immune system tissue in the smell-sensing region of the human nose (human olfactory ecto–mesenchymal stem cells [OE-MSCs]) could provide a source of cells to treat brain disorders in which nerve cells are lost or irreparably damaged.

Stem cells are considered by many to be promising candidate sources of cells for the regeneration and repair ...

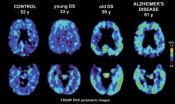

Brain scan identifies patterns of plaques and tangles in adults with Down syndrome

2011-06-14

In one of the first studies of its kind, UCLA researchers used a unique brain scan to assess the levels of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles — the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease — in adults with Down syndrome.

Published in the June edition of the Archives of Neurology, the finding may offer an additional clinical tool to help diagnose dementia in adults with Down syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by the presence of a complete or partial extra copy of chromosome 21.

Adults with this disorder develop Alzheimer's-like plaque and tangle deposits early, ...

Chillingham cattle cowed by climate change

2011-06-14

Spring flowers are opening sooner and songbirds breeding earlier in the year, but scientists know little about how climate change is affecting phenology – the timing of key biological events – in UK mammals. Now, a new study on Northumberland's iconic Chillingham cattle published in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Animal Ecology shows climate change is altering when these animals breed, and fewer calves are surviving as a result.

The team of ecologists lead by Dr Sarah Burthe of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology were able to use the cattle to discover more ...

Pacemaker implantation for heart failure does not benefit nearly half of the patients

2011-06-14

A new meta-analysis study, led by physician researchers at University Hospitals (UH) Case Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, and to be published in the Archives of Internal Medicine (embargoed until June 13, 4 p.m. EDT), shows that three-lead cardiac pacemakers implanted in those with heart failure fail to help up to 40 percent of patients with such devices.

"These findings have significant clinical implications and impact tens of thousands of patients in the U.S.," said Ilke Sipahi, MD, Associate Director of Heart Failure and Transplantation ...

Genetic factor controls health-harming inflammation in obese

2011-06-14

CLEVELAND – June 13, 2011 –Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine have discovered a genetic factor that can regulate obesity-induced inflammation that contributes to chronic health problems.

If they learn to control levels of the factor in defense cells called macrophages, "We have a shot at a novel treatment for obesity and its complications, such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer," said Mukesh K. Jain, MD, Ellery Sedgwick Jr. Chair, director of the Case Cardiovascular Research Institute, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University ...

Promising new target for stifling the growth and spread of cancer

2011-06-14

Cancer and chronic inflammation are partners in peril, with the latter increasing the likelihood that malignant tumors will develop, grow and spread. Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine say they've identified a tumor inflammation trigger that is common to most, if not all, cancers. And using existing inhibitory drugs, the scientists were able to dramatically decrease primary tumor growth in animal studies and, more importantly, halt tumor progression and metastasis.

The findings appear in the June 14 issue of the journal Cancer Cell, ...

Type 2 diabetes linked to higher risk of stroke and CV problems; metabolic syndrome isn't

2011-06-14

CHICAGO – Among patients who have had an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), type 2 diabetes was associated with an increased risk of recurrent stroke or cardiovascular events, but metabolic syndrome was not, according to a report published Online First today by Archives of Neurology, one of the JAMA/Archives journals.

Previous research has examined the association between cardiovascular incidents and these conditions, according to background information in the article. "Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risks of both stroke and coronary ...

Expenditures for glaucoma medications appear to have increased

2011-06-14

CHICAGO – In recent years, spending for glaucoma medications has increased, especially for women, persons who have only public health insurance and those with less than a high school education, according to a report published Online First by Archives of Ophthalmology, one of the JAMA/Archives journals.

Glaucoma is a condition marked by damage to the optic nerve, and is a leading cause of blindness. According to background information in the article, approximately 2.2 million individuals ages 40 years and older in the United States currently have primary open-angle glaucoma; ...

Dietary changes appear to affect levels of biomarkers associated with Alzheimer's disease

2011-06-14

###

(Arch Neurol. 2011;68[6]:743-752. Available pre-embargo to the media at www.jamamedia.org.)

Editor's Note: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and by funding from the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowment. This article results from work supported by resources from the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, financial disclosures, funding and support, etc. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

[Press-News.org] NIH researchers find new clues about agingGenetic splicing mechanism triggers both premature aging syndrome and normal cellular aging