(Press-News.org) Doctors at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are performing a new procedure to treat atrial fibrillation, a common irregular heartbeat.

Available at only a handful of U.S. medical centers, this "hybrid" procedure combines minimally invasive surgical techniques with the latest advances in catheter ablation, a technique that applies scars to the heart's inner surface to block signals causing the heart to misfire. The two-pronged approach gives doctors access to both the inside and outside of the heart at the same time, helping to more completely block the erratic electrical signals that cause atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation affects more than 2 million Americans, a number that continues to increase as the population ages. While not fatal in itself, patients who suffer from atrial fibrillation are at increased risk of stroke and congestive heart failure. And many, especially those who feel the fibrillations, have shortness of breath, chest pain, fatigue and feelings of anxiety, among other problems.

"For some patients, it's a difficult way to live," says Phillip S. Cuculich, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a cardiac electrophysiologist who treats patients with atrial fibrillation at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Atrial fibrillation occurs when the smaller upper chambers of the heart, called atria, get irregular electrical signals that disrupt the coordinated pumping of blood through the heart to the rest of the body. Instead of a normal beat, these signals cause weak flutters that prevent adequate blood flow to the ventricles, the heart's main pumps.

Despite its prevalence, atrial fibrillation remains tricky to treat. Medications that maintain a normal heart rhythm often stop working after a period of time.

When medication is no longer effective, doctors typically recommend catheter ablation, which involves threading long, thin tubes through a vein in the groin into the heart. The tips of these catheters can be heated, allowing doctors to perform a series of ablations, or burns, on the heart's inner surface. The goal of ablation therapy is to create scar tissue that isolates the irregular electrical signals and blocks them from spreading over the heart and causing fibrillation. After a catheter ablation procedure, about 70 percent of patients remain free of symptoms after one year.

Although success rates for catheter ablation are better than medication, catheter ablation does not always work. Some patients may require a second or third procedure to achieve a successful result.

"The heart is a remarkable thing," Cuculich says, "It's very sturdy and can reconnect across those ablation lines."

For hard-to-treat patients, doctors have recommended the Cox-Maze surgical procedure, developed in 1987 by James L. Cox, MD, at Washington University.

The Cox-Maze surgical procedure has a high success rate and is considered the gold standard of atrial fibrillation treatment. The original Cox-Maze procedure has been refined by Ralph J. Damiano Jr., MD, the John M. Shoenberg Professor of Surgery at Washington University, and is effective in 90 percent of patients who undergo it. Damiano has made the procedure easier to perform and more widely available. But many patients consider it too invasive to treat their atrial fibrillation.

"If you have other cardiac surgery that you need, like bypass surgery or valve surgery, and you have atrial fibrillation, the Cox-Maze procedure is an excellent choice to do at the same time," Cuculich says. "But most of my patients just have atrial fibrillation."

To better help these patients, the new hybrid procedure attempts to combine the success rates of the Cox-Maze procedure with the minimally invasive nature and shorter recovery times associated with catheter ablation.

The key is blocking signals that cause the erratic rhythm from both inside and outside the heart at the same time. Because catheters enter through a vein, electrophysiologists only have access to the inside of the heart. A surgeon, in contrast, can provide access to the outside.

"By applying the energy to make scars from both the inside and outside of the heart, we're better able to achieve a full-thickness ablation," says Hersh S. Maniar, MD, assistant professor of surgery at the School of Medicine who performs the new hybrid procedure and the Cox-Maze. "A complete scar that crosses through the full thickness of the heart wall will more permanently block atrial fibrillation signals."

To avoid open surgery, the hybrid procedure is performed through three small incisions under each of the patient's armpits. The surgeons view their work by inserting a small camera into one of the incisions.

After the surgeon has performed the ablations on the outside of the heart, the electrophysiologist uses the catheters inside the heart to attempt to induce a fibrillation, testing the integrity of the ablation lines. If the atrial fibrillation persists, the electrophysiologist can touch up the ablation lines inside the heart until fibrillation can no longer be induced. Finally, the surgeon closes off the left atrial appendage, the area of the heart where most stroke-causing blood clots originate.

According to Maniar, the goal of the hybrid procedure is to develop a minimally invasive, yet highly effective procedure that reduces the risk of stroke and allows more patients with atrial fibrillation to be treated effectively with a single procedure.

A clinical trial is planned to compare the new hybrid procedure to catheter ablation in patients whose atrial fibrillation is persistent, meaning it does not start and stop on its own, and whose left atrium is enlarged. This group of patients has not done well historically with catheter ablation.

But outside the clinical trial, the procedure is now available to any patient with atrial fibrillation after consultation with his or her doctor.

"Right now we're doing this for people who have persistent atrial fibrillation and for people who have had a failed catheter ablation procedure," Cuculich says. "I think this is an important step forward in improving patient quality of life in a less invasive way than traditional surgery."

INFORMATION:

For more information, call Cuculich's office at (314) 454-7698 or Maniar's office at (314) 362-7431.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

New procedure treats atrial fibrillation

2011-06-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Analyzing agroforestry management

2011-06-28

MADISON, WI, JUNE 28, 2011 -- The evaluation of both nutrient and non-nutrient resource interactions provides information needed to sustainably manage agroforestry systems. Improved diagnosis of appropriate nutrient usage will help increase yields and also reduce financial and environmental costs. To achieve this, a management support system that allows for site-specific evaluation of nutrient-production imbalances is needed.

Scientists at the University of Toronto and the University of Saskatchewan have developed a conceptual framework to diagnosis nutrient and non-nutrient ...

Neuroscientists find famous optical illusion surprisingly potent

2011-06-28

VIDEO:

Scientists have figured out the brain mechanism that makes this optical illusion work. The illusion, known as "motion aftereffect " in scientific circles, causes us to see movement where none exist

Click here for more information.

Scientists have come up with new insight into the brain processes that cause the following optical illusion:

Focus your eyes directly on the "X" in the center of the image in this short video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXnUckHbPqM&feature=player_embedded)

The ...

Insight into plant behavior could aid quest for efficient biofuels

2011-06-28

Tiny seawater algae could hold the key to crops as a source of fuel and plants that can adapt to changing climates.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have found that the tiny organism has developed coping mechanisms for when its main food source is in short supply.

Understanding these processes will help scientists develop crops that can survive when nutrients are scarce and to grow high-yield plants for use as biofuels.

The alga normally feeds by ingesting nitrogen from surrounding seawater but, when levels are low, it reduces its intake and instead absorbs ...

Serum-free cultures help transplanted MSCs improve efficacy

2011-06-28

Tampa, Fla. (June 28, 2011) – Mensenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent cells identified in bone marrow and other tissues, have been shown to be therapeutically effective in the immunosuppression of T-cells, the regeneration of blood vessels, assisting in skin wound healing, and suppressing chronic airway inflammation in some asthma cases. Typically, when MSCs are being prepared for therapeutic applications, they are cultured in fetal bovine serum.

A study conducted by a research team from Singapore and published in the current issue of Cell Medicine [2(1)], freely ...

JetBoarder International Launches The 'Sprint', The Worlds First Kids' JetBoarder

2011-06-28

In another world first, Australian Company JetBoarder pioneers the way in the new sport of JetBoarding. Their newest model, which previewed at Sanctuary Cove International Boat Show in Australia, is a real world first.

Click link to see more: http://vimeo.com/24210179

Called the 'Sprint', the focus with the kids' JetBoarder was safety first and fun second, in a new experience for kids aged 12-16. Our SPRINT Model achieves this plus more advises Chris Kanyaro. "We want to give kids the opportunity to enjoy the latest craze taking the world by storm" in ...

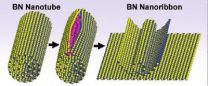

Splitsville for boron nitride nanotubes

2011-06-28

For Hollywood celebrities, the term "splitsville" usually means "check your prenup." For scientists wanting to mass-produce high quality nanoribbons from boron nitride nanotubes, "splitsville" could mean "happily ever after."

Scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley, working with scientists at Rice University, have developed a technique in which boron nitride nanotubes are stuffed with atoms of potassium until the tubes split open along a longitudinal seam. This creates defect-free boron nitride ...

Chemical produced in pancreas prevented and reversed diabetes in mice

2011-06-28

TORONTO, Ont., June 28, 2011—A chemical produced by the same cells that make insulin in the pancreas prevented and even reversed Type 1 diabetes in mice, researchers at St. Michael's Hospital have found.

Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, is characterized by the immune system's destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas that make and secrete insulin. As a result, the body makes little or no insulin.

The only conventional treatment for Type 1 diabetes is insulin injection, but insulin is not a cure as it does not prevent or reverse the loss of ...

Can soda tax curb obesity?

2011-06-28

EVANSTON, Ill. --- To many, a tax on soda is a no-brainer in advancing the nation's war on obesity. Advocates point to a number of studies in recent years that conclude that sugary drinks have a lot to do with why Americans are getting fatter.

But obese people tend to drink diet sodas, and therefore taxing soft drinks with added sugar or other sweeteners is not a good weapon in combating obesity, according to a new Northwestern University study.

An amendment to Illinois Senate Bill 396 would add a penny an ounce to the cost of most soft drinks with added sugar or sweeteners, ...

Inkjet printing could change the face of solar energy industry

2011-06-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Inkjet printers, a low-cost technology that in recent decades has revolutionized home and small office printing, may soon offer similar benefits for the future of solar energy.

Engineers at Oregon State University have discovered a way for the first time to create successful "CIGS" solar devices with inkjet printing, in work that reduces raw material waste by 90 percent and will significantly lower the cost of producing solar energy cells with some very promising compounds.

High performing, rapidly produced, ultra-low cost, thin film solar electronics ...

Silver pen has the write stuff for flexible electronics

2011-06-28

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The pen may have bested the sword long ago, but now it's challenging wires and soldering irons.

University of Illinois engineers have developed a silver-inked rollerball pen capable of writing electrical circuits and interconnects on paper, wood and other surfaces. The pen is writing whole new chapters in low-cost, flexible and disposable electronics.

Led by Jennifer Lewis, the Hans Thurnauer professor of materials science and engineering at the U. of I., and Jennifer Bernhard, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, the team published ...