Neuroscientists find famous optical illusion surprisingly potent

2011-06-28

(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Scientists have figured out the brain mechanism that makes this optical illusion work. The illusion, known as "motion aftereffect " in scientific circles, causes us to see movement where none exist

Click here for more information.

Scientists have come up with new insight into the brain processes that cause the following optical illusion:

Focus your eyes directly on the "X" in the center of the image in this short video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXnUckHbPqM&feature=player_embedded)

The yellow jacket (Rocky, the mascot of the University of Rochester) appears to be expanding. But he is not. He is staying still. We simply think he is growing because our brains have adapted to the inward motion of the background and that has become our new status quo. Similar situations arise constantly in our day-to-day lives – jump off a moving treadmill and everything around you seems to be in motion for a moment.

This age-old illusion, first documented by Aristotle, is called the Motion Aftereffect by today's scientists. Why does it happen, though? Is it because we are consciously aware that the background is moving in one direction, causing our brains to shift their frame of reference so that we can ignore this motion? Or is it an automatic, subconscious response?

Davis Glasser, a doctoral student in the University of Rochester's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences thinks he has found the answer. The results of a study done by Glasser, along with his advisor, Professor Duje Tadin, and colleagues James Tsui and Christopher Pack of the Montreal Neurological Institute, will be published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

In their paper, the scientists show that humans experience the Motion Aftereffect even if the motion that they see in the background is so brief that they can't even tell whether it is heading to the right or the left.

Even when shown a video of a pattern that is moving for only 1/40 of a second (25 milliseconds) – so short that the direction it is moving cannot be consciously distinguished – a subject's brain automatically adjusts. If the subject is then shown a stationary object, it will appear to him as though it is moving in the opposite direction of the background motion. In recordings from a motion center in the brain called cortical area MT, the researchers found neurons that, following a brief exposure to motion, respond to stationary objects as if they are actually moving. It is these neurons that the researchers think are responsible for the illusory motion of stationary objects that people see during the Motion Aftereffect.

This discovery reveals that the Motion Aftereffect illusion is not just a compelling visual oddity: It is caused by neural processes that happen essentially every time we see moving objects. The next phase of the group's study will attempt to find out whether this rapid motion adaptation serves a beneficial purpose – in other words, does this rapid adaptation actually improve your ability to estimate the speed and direction of relevant moving objects, such as a baseball flying toward you.

###

About the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester (www.rochester.edu) is one of the nation's leading private universities. Located in Rochester, N.Y., the University gives students exceptional opportunities for interdisciplinary study and close collaboration with faculty through its unique cluster-based curriculum. Its College, School of Arts and Sciences, and Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences are complemented by the Eastman School of Music, Simon School of Business, Warner School of Education, Laboratory for Laser Energetics, Schools of Medicine and Nursing, and the Memorial Art Gallery.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011-06-28

Tiny seawater algae could hold the key to crops as a source of fuel and plants that can adapt to changing climates.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have found that the tiny organism has developed coping mechanisms for when its main food source is in short supply.

Understanding these processes will help scientists develop crops that can survive when nutrients are scarce and to grow high-yield plants for use as biofuels.

The alga normally feeds by ingesting nitrogen from surrounding seawater but, when levels are low, it reduces its intake and instead absorbs ...

2011-06-28

Tampa, Fla. (June 28, 2011) – Mensenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent cells identified in bone marrow and other tissues, have been shown to be therapeutically effective in the immunosuppression of T-cells, the regeneration of blood vessels, assisting in skin wound healing, and suppressing chronic airway inflammation in some asthma cases. Typically, when MSCs are being prepared for therapeutic applications, they are cultured in fetal bovine serum.

A study conducted by a research team from Singapore and published in the current issue of Cell Medicine [2(1)], freely ...

2011-06-28

In another world first, Australian Company JetBoarder pioneers the way in the new sport of JetBoarding. Their newest model, which previewed at Sanctuary Cove International Boat Show in Australia, is a real world first.

Click link to see more: http://vimeo.com/24210179

Called the 'Sprint', the focus with the kids' JetBoarder was safety first and fun second, in a new experience for kids aged 12-16. Our SPRINT Model achieves this plus more advises Chris Kanyaro. "We want to give kids the opportunity to enjoy the latest craze taking the world by storm" in ...

2011-06-28

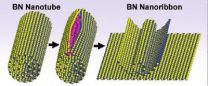

For Hollywood celebrities, the term "splitsville" usually means "check your prenup." For scientists wanting to mass-produce high quality nanoribbons from boron nitride nanotubes, "splitsville" could mean "happily ever after."

Scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley, working with scientists at Rice University, have developed a technique in which boron nitride nanotubes are stuffed with atoms of potassium until the tubes split open along a longitudinal seam. This creates defect-free boron nitride ...

2011-06-28

TORONTO, Ont., June 28, 2011—A chemical produced by the same cells that make insulin in the pancreas prevented and even reversed Type 1 diabetes in mice, researchers at St. Michael's Hospital have found.

Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, is characterized by the immune system's destruction of the beta cells in the pancreas that make and secrete insulin. As a result, the body makes little or no insulin.

The only conventional treatment for Type 1 diabetes is insulin injection, but insulin is not a cure as it does not prevent or reverse the loss of ...

2011-06-28

EVANSTON, Ill. --- To many, a tax on soda is a no-brainer in advancing the nation's war on obesity. Advocates point to a number of studies in recent years that conclude that sugary drinks have a lot to do with why Americans are getting fatter.

But obese people tend to drink diet sodas, and therefore taxing soft drinks with added sugar or other sweeteners is not a good weapon in combating obesity, according to a new Northwestern University study.

An amendment to Illinois Senate Bill 396 would add a penny an ounce to the cost of most soft drinks with added sugar or sweeteners, ...

2011-06-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Inkjet printers, a low-cost technology that in recent decades has revolutionized home and small office printing, may soon offer similar benefits for the future of solar energy.

Engineers at Oregon State University have discovered a way for the first time to create successful "CIGS" solar devices with inkjet printing, in work that reduces raw material waste by 90 percent and will significantly lower the cost of producing solar energy cells with some very promising compounds.

High performing, rapidly produced, ultra-low cost, thin film solar electronics ...

2011-06-28

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The pen may have bested the sword long ago, but now it's challenging wires and soldering irons.

University of Illinois engineers have developed a silver-inked rollerball pen capable of writing electrical circuits and interconnects on paper, wood and other surfaces. The pen is writing whole new chapters in low-cost, flexible and disposable electronics.

Led by Jennifer Lewis, the Hans Thurnauer professor of materials science and engineering at the U. of I., and Jennifer Bernhard, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, the team published ...

2011-06-28

Stepladders, a household product used by thousands of people every day, are a surprisingly common cause of injury. In 2009, more than 187,000 Americans visited the hospital after sustaining stepladder injuries, many of which resulted from a fall. A recent human factors/ergonomics study explores how improved design and user behavior can decrease the likelihood of future accidents.

In their upcoming HFES 55th Annual Meeting presentation, "The Role of Human Balance in Stepladder Accidents," HF/E researchers Daniel Tichon, Lowell Baker, and Irving Ojalvo review research ...

2011-06-28

Cambridge, Mass. - June 28, 2011 - At a glance, a painting by Jackson Pollock (1912) can look deceptively accidental: just a quick flick of color on a canvas.

A quantitative analysis of Pollock's streams, drips, and coils, by Harvard mathematician L. Mahadevan and collaborators at Boston College, reveals, however, that the artist had to be slow—he had to be deliberate—to exploit fluid dynamics in the way that he did.

The finding, published in Physics Today, represents a rare collision between mathematics, physics, and art history, providing new insight into ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Neuroscientists find famous optical illusion surprisingly potent