(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA - The lab of Kevin Foskett, PhD, the Isaac Ott Professor of Physiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, has found a possible new target for fighting cystic fibrosis (CF) that could compensate for the lack of a functioning ion channel in affected CF-related cells. Their finding appears in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The team explored the role of CFTR, the chloride ion channel mutated in CF patients, in fluid secretion by mucous gland cells. They used a recently developed transgenic pig model, in which the CFTR gene has been knocked out. The CFTR gene provides instructions for making a channel that transports negatively charged particles called chloride ions into and out of cells. The flow of chloride ions helps control the movement of water in tissues, which is necessary for the production of thin, freely flowing mucous.

CF researchers had been held back because existing animal models did not fully mimic the problems seen in people with CF. In people, faulty mucous glands may contribute to airway dehydration and the problems associated with CF. Mucous glands found in the airways of the lung are important to breathing because they help clear inhaled irritants and bacteria. They are also the sites where important macromolecules critical for lung defense against pathogens are made.

CF is the most common genetic disease in the United States, affecting about 30,000 children and adults and about 70,000 worldwide. The CF mutation makes certain organs of the body susceptible to obstruction due to thick mucus secretions, especially in the lung where thick secretions lead to chronic infections. This requires a daily regimen of drugs and physical therapy to help clear airway secretions.

"We discovered, first, that the ion transport and signal transduction mechanisms in the pig cells appear to be precisely the same as those used in human cells, indicating that the pig is an excellent model for studies of human lung function and a valuable tool for elucidating pathology of lung disease in CF," notes Foskett.

The team also discovered that fluid secretion by the mucous cells -- in response to neurotransmitters -- requires CFTR. This secretion was absent in the pigs lacking CFTR. However, the same cells that lacked the CFTR chloride ion channel, mimicking the condition in human CF, expressed another, different chloride ion channel that could be activated by elevating intracellular calcium by the same neurotransmitters. The presence of both channels in the same mucous cells suggests that the calcium-activated chloride channel could be targeted therapeutically to compensate for lack of CFTR functioning channels in CF-harmed cells.

"This crosstalk between the signaling pathways that activate the two different chloride ion channels now gives us a completely new therapeutic strategy to think about," says Foskett. For example, the presence of the calcium-activated chloride channel would enable CF mucous cells to secrete in response to stimulation that would have normally required the CFTR channel. Drugs that could enhance the magnitude of the calcium response might also enable activation of calcium-activated chloride channel-mediated secretion in CF cells. Importantly, such agents might be able to lead to secretion only during times of physiological stimulus, utilizing the appropriate neural regulation of secretion that likely remains intact in CF.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $3.6 billion enterprise.

Penn's School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools, and is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $367.2 million awarded in the 2008 fiscal year.

Penn Medicine's patient care facilities include:

The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania – the nation's first teaching hospital, recognized as one of the nation's top 10 hospitals by U.S. News & World Report.

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center – named one of the top 100 hospitals for cardiovascular care by Thomson Reuters for six years.

Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751, nationally recognized for excellence in orthopaedics, obstetrics & gynecology, and behavioral health.

Additional patient care facilities and services include Penn Medicine at Rittenhouse, a Philadelphia campus offering inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient care in many specialties; as well as a primary care provider network; a faculty practice plan; home care and hospice services; and several multispecialty outpatient facilities across the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2009, Penn Medicine provided $733.5 million to benefit our community.

Channeling efforts to fight cystic fibrosis

Crosstalk between ion channels points to new therapeutic strategy, Penn study finds

2010-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Women with diabetes having more C-sections and fetal complications: study

2010-09-18

TORONTO, September 17, 2010 – Nearly half of women with diabetes prior to pregnancy have a potentially-avoidable C-section and their babies are twice as likely to die as those born to women without diabetes, according to the POWER study.

Researchers from St. Michael's Hospital, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and Women's College Hospital say rates of diabetes in Ontario have doubled in the last 12 years. Nearly one in 10 Ontario adults has been diagnosed with diabetes, including more women than ever before.

As women develop type 2 diabetes (adult ...

Progress against child deaths will lag until family, community care prioritized

2010-09-18

Global efforts to tackle millions of preventable child and maternal deaths will fail to extend gains unless world leaders act now to pour more healthcare resources directly into families and communities, according to a new World Vision report launched today.

"The Missing Link: Saving children's lives through family care" examines how the resources invested to achieve Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4 and 5 can go further toward saving the more than 8 million children under the age of five and 350,000 mothers who die each year, mostly from preventable causes. Undertaken ...

NASA eyes Typhoon Fanapi approaching Taiwan

2010-09-18

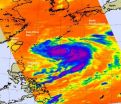

Infrared satellite data from NASA's Aqua satellite revealed strong convection and a tight circulation center within Typhoon Fanapi as it heads for a landfall in Taiwan this weekend.

At 1500 UTC (10 a.m. EDT) on Sept. 17, Typhoon Fanapi's maximum sustained winds were near 85 knots (97 mph). It was centered about 360 nautical miles east-southeast of Taipei, Taiwan near 23.2 North and 127.4 East. It is churning up high seas up to 22 feet.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Typhoon Fanapi on September 17 at 04:45 UTC (12:45 a.m. EDT) and captured an infrared image of its ...

Tick tock: Rods help set internal clocks, biologist says

2010-09-18

We run our modern lives largely by the clock, from the alarms that startle us out of our slumbers and herald each new workday to the watches and clocks that remind us when it's time for meals, after-school pick-up and the like.

In addition to those ubiquitous timekeepers, though, we have internal "clocks" that are part of our biological machinery and which help set our circadian rhythms, regulating everything from our sleep-wake cycles to our appetites and hormone levels. Light coming into our brains via our eyes set those clocks, though no one is sure exactly how this ...

NASA's CloudSat satellite and GRIP Aircraft profile Hurricane Karl

2010-09-18

NASA's CloudSat satellite captured a profile of Hurricane Karl as it began making landfall in Mexico today. The satellite data revealed very high, icy cloud tops in Karl's powerful thunderstorms, and moderate to heavy rainfall from the storm. Meanwhile, NASA's "GRIP" mission was also underway as aircraft were gathering valuable data about Hurricane Karl as he moves inland.

NASA's Genesis and Rapid Intensification Processes mission (known as GRIP) is still underway and is studying the rapid intensification of storms, and that's exactly what Karl did on Thursday Sept. ...

NASA sees record-breaking Julia being affected by Igor

2010-09-18

Julia is waning in the eastern Atlantic Ocean because of outflow from massive Hurricane Igor, despite his distance far to the west. Satellite imagery from NASA's Aqua satellite showed that Julia's eye was no longer visible, a sign that she's weakening.

As NASA's Aqua satellite flew over Hurricane Julia from space on Sept. 16 at 1:35 p.m. EDT, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument captured a visible image of the storm. In the MODIS image, Julia's eye was no longer visible and its center was cloud-filled.

Although Julia is weakening from ...

Pickle spoilage bacteria may help environment

2010-09-18

Spoilage bacteria that can cause red coloration of pickles' skin during fermentation may actually help clean up dyes in textile industry wastewater, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) study.

Some species of Lactobacilli-food-related microorganisms-can cause red coloring when combined with tartrazine, a yellow food-coloring agent used in the manufacture of dill pickles. Now Agricultural Research Service (ARS) microbiologist Ilenys Pérez-Díaz and her colleagues have found that these spoilage Lactobacilli also may have environmental benefits. ARS is ...

Gene limits learning and memory in mice

2010-09-18

Deleting a certain gene in mice can make them smarter by unlocking a mysterious region of the brain considered to be relatively inflexible, scientists at Emory University School of Medicine have found.

Mice with a disabled RGS14 gene are able to remember objects they'd explored and learn to navigate mazes better than regular mice, suggesting that RGS14's presence limits some forms of learning and memory.

The results were published online this week in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Since RGS14 appears to hold mice back mentally, ...

Research team assesses environmental impact of organic solar cells

2010-09-18

Solar energy could be a central alternative to petroleum-based energy production. However, current solar-cell technology often does not produce the same energy yield and is more expensive to mass-produce. In addition, information on the total effect of solar energy production on the environment is incomplete, experts say.

To better understand the energy and environmental benefits and detriments of solar power, a research team from Rochester Institute of Technology has conducted one of the first life-cycle assessments of organic solar cells. The study found that the embodied ...

Researchers at SUNY Downstate find drug combination may treat traumatic brain injury

2010-09-18

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a serious public health problem in the United States. Recent data show that approximately 1.7 million people sustain a traumatic brain injury annually. While the majority of TBIs are concussions or other mild forms, traumatic brain injuries contribute to a substantial number of deaths and cases of permanent disability.

Currently, there are no drugs available to treat TBI: a variety of single drugs have failed clinical trials, suggesting a possible role for drug combinations. Testing this hypothesis in an animal model, researchers at SUNY ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

[Press-News.org] Channeling efforts to fight cystic fibrosisCrosstalk between ion channels points to new therapeutic strategy, Penn study finds