(Press-News.org) Networks of biologically-connected marine protected areas need to be carefully planned, taking into account the open ocean migrations of marine fish larvae that take them from one home to another sometimes hundreds of kilometers away.

Research published today in the international journal Oecologia sheds new light on the dispersal of marine fish in their larval stages, important information for the effective design of marine protected areas (MPAs), a widely advocated conservation tool.

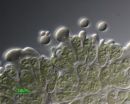

Using a novel genetic analysis, researchers at the University of Windsor, Canada, and the United Nations University's Canadian-based Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH) studied dispersal and connectivity among populations of the bicolor damselfish -- a species common to Caribbean coral reefs and a convenient proxy for many coral reef fish species with similar biology, including a typical 30-day larval stage.

Using samples of newly settled juvenile fish from sites in Belize and Mexico, they traced the origins of hundreds of individual fish larvae back to putative source populations.

"This is the first time that genetic 'assignment tests' have been used to delineate the pattern of connectivity for a marine fish in a region of this size (approximately 6,000 square kilometers)," says lead author Derek Hogan of the University of Windsor, now at University of Wisconsin.

"We found that larvae of this species, on average, traveled 77 km from home in the 30-day larval period," says Dr. Hogan. "Although some fish remained close to home in the same period, some traveled almost 200 km - roughly the distance from New York City to Albany - an impressive feat for a larva about the size of a baby fingernail."

The scientists were surprised to find that patterns of larval dispersal among reefs changed from year to year, driven perhaps by changes in oceanographic currents or meteorological events.

"These results show that it is possible to characterize the pattern of connectivity for selected species, with considerable detail" says co-author Prof. Daniel Heath of the University of Windsor.

"These studies are invaluable for understanding how to design networks of marine protected areas effectively," says Dr. Hogan. "The functioning, and therefore the success, of networks of MPAs designed for conserving species depends fundamentally on our deep understanding of larval migrations."

The authors caution that more work is needed to determine factors that cause larval dispersal to fluctuate from year to year.

"Our results reveal that developing a precise understanding of connectivity patterns is going to be more difficult than previously assumed, because they vary through time," says co-author Peter F. Sale, Assistant Director at UNU-INWEH.

"Long-term, we need to be building models that can simulate connectivity in ways that reproduce these year-to-year changes. Models that can do that will be broadly applicable and powerful management tools."

The study is part of the Coral Reef Targeted Research Project (CRTR), a World Bank and University of Queensland-led project funded by the Global Environment Facility. CRTR involves over 100 investigators from universities and research centers worldwide. Its Connectivity Working Group, led by Dr. Sale and managed by UNU-INWEH, focuses its research activity primarily in the western Caribbean.

These results add to the CRTR Project's impressive total of new science results on selected questions deemed key to improving management of coral reef systems worldwide.

###

Further more information:

The Connectivity Program:

www.inweh.unu.edu/Coastal/CoralReef/Coralmainpage.htm

The CRTR Project:

www.gefcoral.org

UNU-INWEH was established in 1996 to strengthen water management capacity, particularly of developing countries, and to provide on-the-ground project support. With core funding from the Government of Canada through CIDA, it is hosted by McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

The University of Windsor is an internationally-oriented, multi-disciplined institution that actively fosters an atmosphere of close cooperation between faculty and students, creating a unifying atmosphere of excellence across all of its faculties to encourage lifelong learning, teaching, research and discovery.

Data revealing migrations of larval reef fish vital for designing networks of marine protected areas

2011-07-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New brain research suggests eating disorders impact brain function

2011-07-12

AURORA, Colo. (July 11, 2011) Bulimia nervosa is a severe eating disorder associated with episodic binge eating followed by extreme behaviors to avoid weight gain such as self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or excessive exercise. It is poorly understood how brain function may be involved in bulimia. A new study led by Guido Frank, MD, assistant professor, Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience and Director, Developmental Brain Research Program at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, studied the brain response to a dopamine related reward-learning ...

The deVere Group Launches the Alquity Africa Fund

2011-07-12

The Alquity Africa equity investment fund targets double-digit returns from Africa's high-growth economies.

Notably, it achieved a 10% return for investors in its maiden year. In addition, Alquity Investment Management, the fund's investment manager, has committed to donating a minimum of 25% of its net management fees on an ongoing basis to projects aimed at transforming lives across Africa. As the donation comes from Alquity's management fees, investors still receive their full investment return.

The Alquity Africa Fund will be available to invest in via The deVere ...

New study may lead to quicker diagnosis, improved treatment for fatal lung disease

2011-07-12

SALT LAKE CITY – One-fifth of all patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension suffer with the fatal disease for more than two years before being correctly diagnosed and properly treated, according to a new national study led by researchers at Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City.

"For a lot of patients, that means the treatment is more difficult and the damage is irreversible," said Lynnette Brown, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist and researcher at Intermountain Medical Center and lead author of the study, which is published this week in the July issue of Chest, the ...

Georgia hospitals lag in palliative care for the seriously ill, UGA study finds

2011-07-12

Hospitals across the nation are increasingly implementing palliative care programs to help patients manage the physical and emotional burdens of serious illnesses, but a new University of Georgia study finds that 82 percent of the state's hospitals do not offer palliative care services.

"Most people will have some sort of extended illness at the end of their life, and many, especially frail elders, could benefit from this type of care," said study principal investigator Anne Glass, assistant director of the UGA Institute of Gerontology, part of the College of Public Health. ...

U of T research suggests female minorities are more affected by racism than sexism

2011-07-12

Studies by the University of Toronto's psychology department suggest that racism may impact some female minority groups more deeply than sexism.

"We found that Asian women take racism more personally and find it more depressing than sexism," said lead author and doctoral student Jessica Remedios.

"In order to understand the consequences for people who encounter prejudice, we must consider the type of prejudice they are facing," says Remedios.

In one study, 66 participants of Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Taiwanese and Japanese descent were assigned one of three hypothetical ...

University of Kentucky-led research could be path to new energy sources

2011-07-12

LEXINGTON, Ky. − A team of researchers led by University of Kentucky College of Agriculture Professor Joe Chappell is making a connection from prehistoric times to the present that could result in being able to genetically create a replacement for oil and coal shale deposits. This could have fundamental implications for the future of the earth's energy supply.

Tom Niehaus, completing his doctorate in the Chappell laboratory; Shigeru Okada, a sabbatical professor from the aquatic biosciences department at the University of Tokyo; Tim Devarenne, a UK graduate and ...

New research shows forest trees remember their roots

2011-07-12

Toronto, ON - When it comes to how they respond to the environment, trees may not be that different from humans.

Recent studies showed that even genetically identical human twins can have a different chance of getting a disease. This is because each twin has distinct personal experiences through their lifetime.

It turns out that the same is likely true for forest trees as well, according to new research from the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC).

"The findings were really quite stunning," says Malcolm Campbell, a biologist and lead author of the study. "People ...

Multiple 'siblings' from every gene: Alternate gene reading leads to alternate gene products

2011-07-12

A genome-wide survey by researchers at The Wistar Institute shows how our cells create alternate versions of mRNA transcripts by altering how they "read" DNA. Many genes are associated with multiple gene promoters, the researchers say, which is the predominant way multiple variants of a given gene, for example, can be made with the same genetic instructions.

Their findings, which appear in the journal Genome Research, available online now, show how genes are read in developing and adult brains, and identify the changes in reading DNA that accompany brain development. ...

Researchers identify key role of microRNAs in melanoma metastasis

2011-07-12

Researchers at the NYU Cancer Institute, an NCI-designated cancer center at NYU Langone Medical Center, identified for the first time the key role specific microRNAs (miRNAs) play in melanoma metastasis to simultaneously cause cancer cells to invade and immunosuppress the human body's ability to fight abnormal cells. The new study is published in the July 11, 2011 issue of the journal Cancer Cell.

Researchers performed a miRNA analysis of human melanoma tissues, including primary and metastatic tumors. They found in both sets of tumor cells significantly high levels ...

Malaria parasites use camouflage to trick immune defences of pregnant women

2011-07-12

Researchers from Rigshospitalet – Copenhagen University Hospital – and the University of Copenhagen have discovered why malaria parasites are able to hide from the immune defences of expectant mothers, allowing the parasite to attack the placenta. The discovery is an important part of the efforts researchers are making to understand this frequently fatal disease and to develop a vaccine.

Staff member at CMP. Photo: Lars Hviid"We have found one likely explanation for the length of time it takes for the expectant mother's immune defences to discover the infection in the ...