(Press-News.org) Contact: Christina DeAngelis

christina.deangelis@case.edu

216-368-3635

Kevin Mayhood

kevin.mayhood@case.edu

216-368-5004

Case Western Reserve University

Case Western Reserve restores breathing after spinal cord injury in rodent model

Study published in the online issue of Nature on July 14

CLEVELAND – July 13, 2011 –Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine bridged a spinal cord injury and biologically regenerated lost nerve connections to the diaphragm, restoring breathing in an adult rodent model of spinal cord injury. The work, which restored 80 to more than 100 percent of breathing function, will be published in the online issue of the journal Nature July 14. The scientists say that more testing is necessary, but are hopeful their technique will quickly be used in clinical trials.

Restoration of breathing is the top desire of people with upper spinal cord injuries. Respiratory infections, which attack through the ventilators they rely on, are their top killer.

"We've shown for the very first time that robust, long distance regeneration can restore function of the respiratory system fully," said Jerry Silver, professor of neurosciences at Case Western Reserve and senior author.

Silver has been working 30 years on technologies to restore function to the nearly 1.2 million sufferers of spinal cord injuries. This restoration was accomplished using an old technology – a peripheral nerve graft, and a new technology – an enzyme, he explained.

Using a graft from the sciatic nerve, surgeons have been able to restore function to damaged peripheral nerves in the arms or legs for 100 years. But, they've had little or no success in using a graft on the spinal cord. Nearly 20 years ago, Silver found that after a spinal injury, a structural component of cartilage, called chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, was present and involved in the scarring that prevents axons from regenerating and reconnecting. Silver knew that the bacteria Proteus vulgaris produced an enzyme called Chondroitinase ABC, which could break down such structures. In previous testing, he found that the enzyme clips the inhibitory sugary branches of proteoglycans, essentially opening routes for nerves to grow through.

In this study, the researchers used a section of peripheral nerve to bridge a spinal cord injury at the second cervical level, which had paralyzed one-half of the diaphragm. They then injected Chondroitinase ABC. The enzyme opens passageways through scar tissue formed at the insertion site and promotes neuron growth and plasticity. Within the graft, Schwann cells, which provide structural support and protection to peripheral nerves, guide and support the long-distance regeneration of the severed spinal nerves. Nearly 3,000 severed nerves entered the bridge and 400 to 500 nerves grew out the other side, near disconnected motor neurons that control the diaphragm. There, Chondroitinase ABC prevented scarring from blocking continued growth and reinnervation.

"All the nerves hook up with interneurons and somehow unwanted activities are filtered out but signals for breathing come through," Silver said. "The spinal cord is smart."

Three months after the procedure, tests recording nerve and muscle activity showed that 80 to more than 100 percent of breathing function was restored. Breathing function was maintained at the same levels six months after treatment. A video about the research can be found at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1YKVOAkdInM.

Silver's lab has already begun preliminary work to restore bladder function – the top request of people who suffer lower spinal cord injuries. He is unsure whether the technique would be useful in restoring something as complicated as walking, but for breathing or holding and expelling urine, he said the tests so far indicate the procedure works well.

How long after injury the nerves are still capable of regeneration and re-connection, he doesn't know. But, Silver believes that more than the newly-injured could potentially benefit from the procedure.

###

About Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Founded in 1843, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine is the largest medical research institution in Ohio and is among the nation's top medical schools for research funding from the National Institutes of Health. The School of Medicine is recognized throughout the international medical community for outstanding achievements in teaching. The School's innovative and pioneering Western Reserve2 curriculum interweaves four themes--research and scholarship, clinical mastery, leadership, and civic professionalism--to prepare students for the practice of evidence-based medicine in the rapidly changing health care environment of the 21st century. Eleven Nobel Laureates have been affiliated with the school.

Annually, the School of Medicine trains more than 800 M.D. and M.D./Ph.D. students and ranks in the top 25 among U.S. research-oriented medical schools as designated by U.S. News & World Report "Guide to Graduate Education."

Case Western Reserve restores breathing after spinal cord injury in rodent model

Study published in the online issue of Nature on July 14

2011-07-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Efficient process using microrna converts human skin cells into neurons, Stanford study shows

2011-07-14

STANFORD, Calif. — The addition of two particular gene snippets to a skin cell's usual genetic material is enough to turn that cell into a fully functional neuron, report researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine. The finding, to be published online July 13 in Nature, is one of just a few recent reports of ways to create human neurons in a lab dish.

The new capability to essentially grow neurons from scratch is a big step for neuroscience research, which has been stymied by the lack of human neurons for study. Unlike skin cells or blood cells, neurons ...

Penn study shows link between immune system suppression and blood vessel formation in tumors

2011-07-14

PHILADELPHIA - Targeted therapies that are designed to suppress the formation of new blood vessels in tumors, such as Avastin (bevacizumab), have slowed cancer growth in some patients. However, they have not produced the dramatic responses researchers initially thought they might. Now, research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania might help to explain the modest responses. The discovery, published in the July 14 issue of Nature, suggests novel treatment combinations that could boost the power of therapies based on slowing blood vessel ...

New study confirms the existence of 'trial effect' in HIV clinical trials

2011-07-14

A new study by investigators from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine has confirmed the existence of a "trial effect" in clinical trials for treatment of HIV.

Trial effect is an umbrella term for the benefit experienced by study participants simply by virtue of their participating in the trial. It includes the benefit of newer and more effective treatments, the way those treatments are delivered, increased care and follow-up, and the patient's own behavior change as a result of being under observation.

"Trial effect is notoriously difficult ...

EzPaycheck Software Makes Changing to Computerized Payroll Quick and Painless for Small Businesses

2011-07-14

Changing from running payroll by hand to computerized payroll can be quick and painless. Small business-focused payroll software developer Halfpricesoft.com announced the launch of new improved ezPaycheck payroll software and small business owners can get a free, 30-day trial by downloading ezPaycheck software from http://www.halfpricesoft.com/payroll_software_download.asp.

This trial version contains all of the features and functions of the full version, except tax form printing, allowing customers to thoroughly test drive the product. Once customers are satisfied that ...

Diesel fumes pose risk to heart as well as lungs, study shows

2011-07-14

Tiny chemical particles emitted by diesel exhaust fumes could raise the risk of heart attacks, research has shown.

Scientists have found that ultrafine particles produced when diesel burns are harmful to blood vessels and can increase the chances of blood clots forming in arteries, leading to a heart attack or stroke.

The research by the University of Edinburgh measured the impact of diesel exhaust fumes on healthy volunteers at levels that would be found in heavily polluted cities.

Scientists compared how people reacted to the gases found in diesel fumes – such as ...

New research demonstrates damaging influence of media on public perceptions of chimpanzees

2011-07-14

(Chicago, July 13, 2011)– How influential are mass media portrayals of chimpanzees in television, movies, advertisements and greeting cards on public perceptions of this endangered species? That is what researchers based at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo sought to uncover in a new nationwide study published today in in PLoS One, the open-access journal of the Public Library of Sciences. Their findings reveal the significant role that media plays in creating widespread misunderstandings about the conservation status and nature of this great ape.

A majority of study respondents ...

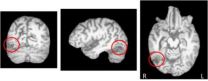

Carnegie Mellon and Princeton neuroscientists uncover neural mechanisms of object recognition

2011-07-14

PITTSBURGH—Certain brain injuries can cause people to lose the ability to visually recognize objects — for example, confusing a harmonica for a cash register.

Neuroscientists from Carnegie Mellon University and Princeton University examined the brain of a person with object agnosia, a deficit in the ability to recognize objects that does not include damage to the eyes or a general loss in intelligence, and have uncovered the neural mechanisms of object recognition. The results, published by Cell Press in the July 15th issue of the journal Neuron, describe the functional ...

New research reveals soil microbes accelerate global warming

2011-07-14

More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere causes soil to release the potent greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide, new research published in this week's edition of Nature reveals. "This feedback to our changing atmosphere means that nature is not as efficient in slowing global warming as we previously thought," said Dr Kees Jan van Groenigen, Research Fellow at the Botany department at the School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, and lead author of the study.

Van Groenigen, along with colleagues from Northern Arizona University and the University of Florida, ...

1 more way plants help human health

2011-07-14

A tiny plant called Arabidopsis thaliana just helped scientists unearth new clues about the daily cycles of many organisms, including humans. This is the latest in a long line of research, much of it supported by the National Institutes of Health, that uses plants to solve puzzles in human health.

While other model organisms may seem to have more in common with us, greens like Arabidopsis provide an important view into genetics, cell division and especially light sensing, which drives 24-hour behavioral cycles called circadian rhythms.

Some human cells, including ...

Natural gas produced from fine milling of precious metals

2011-07-14

Roger Anderson, President of X9 Gold Development, Inc., announced today that multiple tests conducted over the past 18 months have demonstrated that carbon in precious metal ores can be converted to natural gas (methane) during fine milling utilizing X9 Gold's Bubble Mill Technology.

"Over 250 milling processes on a variety of ores have yielded the production of natural gas (methane) as a by-product of the milling process. The amount of natural gas generated seems to be in direct proportion to the carbon content of the ore. "

Mr. Anderson also explained that, "The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] Case Western Reserve restores breathing after spinal cord injury in rodent modelStudy published in the online issue of Nature on July 14