(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH—Certain brain injuries can cause people to lose the ability to visually recognize objects — for example, confusing a harmonica for a cash register.

Neuroscientists from Carnegie Mellon University and Princeton University examined the brain of a person with object agnosia, a deficit in the ability to recognize objects that does not include damage to the eyes or a general loss in intelligence, and have uncovered the neural mechanisms of object recognition. The results, published by Cell Press in the July 15th issue of the journal Neuron, describe the functional neuroanatomy of object agnosia and suggest that damage to the part of the brain critical for object recognition can have a widespread impact on remote parts of the cortex.

"One of the persisting controversies in the field of visual neuroscience concerns the regions of cortex that subserve the human ability to recognize objects as efficiently and accurately as we do, and it's been an elusive topic until now," said Marlene Behrmann, professor of psychology at CMU and a renowned expert in using brain imaging to study the visual perception system.

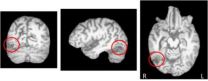

To gain new insight into the neural basis of object recognition, the research team used neuroimaging and behavioral investigations to study visual and object-selective responses in the cortex of healthy controls and a participant called SM who, following selective brain damage to the right hemisphere of the brain, exhibited object agnosia.

The researchers discovered that the functional organization of the "lower" visual cortex, where the image from the retina is initially processed, was similar in SM and control subjects. However, SM exhibited decreased object-selective responses in the brain tissue in and around the brain lesion, and in more distant cortical areas that are also known to be involved in object recognition. Unexpectedly, the decrease in object-selective responses was also observed in corresponding locations of SM's structurally intact left hemisphere.

"What was perhaps the most dramatic, controversial and counter-intuitive result was that while the lesion was in the right hemisphere, and quite small, we found that the same region in the left hemisphere was also not operating normally," Behrmann said.

She added, "These results will force us in the field to step back a little and rethink the way we understand the relationship between brain and behavior. We now need to take into account that there are multiple parts of the brain that underlie object recognition, and damage to any one of those parts can essentially impair or decrease the ability to normally recognize objects."

Additionally, the researchers found that an area of the brain called the right lateral fusiform gyrus is vital for object recognition. There also appeared to be some functional reorganization in intact regions of SM's damaged right hemisphere, suggesting that neural plasticity is possible even when the brain is damaged in adulthood.

"To our knowledge, this study constitutes the most extensive functional analysis of the neural substrate underlying object agnosia and offers powerful evidence concerning the neural representations mediating object perception in normal vision," said Christina Konen, a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton and lead author of the study.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

For more information, watch this short video of CMU's Marlene Behrmann describing the study and results: http://youtu.be/LLyXo60ovX4.

Carnegie Mellon and Princeton neuroscientists uncover neural mechanisms of object recognition

Findings will force researchers to rethink basic assumptions of visual neuroscience

2011-07-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New research reveals soil microbes accelerate global warming

2011-07-14

More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere causes soil to release the potent greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide, new research published in this week's edition of Nature reveals. "This feedback to our changing atmosphere means that nature is not as efficient in slowing global warming as we previously thought," said Dr Kees Jan van Groenigen, Research Fellow at the Botany department at the School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, and lead author of the study.

Van Groenigen, along with colleagues from Northern Arizona University and the University of Florida, ...

1 more way plants help human health

2011-07-14

A tiny plant called Arabidopsis thaliana just helped scientists unearth new clues about the daily cycles of many organisms, including humans. This is the latest in a long line of research, much of it supported by the National Institutes of Health, that uses plants to solve puzzles in human health.

While other model organisms may seem to have more in common with us, greens like Arabidopsis provide an important view into genetics, cell division and especially light sensing, which drives 24-hour behavioral cycles called circadian rhythms.

Some human cells, including ...

Natural gas produced from fine milling of precious metals

2011-07-14

Roger Anderson, President of X9 Gold Development, Inc., announced today that multiple tests conducted over the past 18 months have demonstrated that carbon in precious metal ores can be converted to natural gas (methane) during fine milling utilizing X9 Gold's Bubble Mill Technology.

"Over 250 milling processes on a variety of ores have yielded the production of natural gas (methane) as a by-product of the milling process. The amount of natural gas generated seems to be in direct proportion to the carbon content of the ore. "

Mr. Anderson also explained that, "The ...

VOICE study will continue as it considers what action to take after results of 2 trials

2011-07-14

PITTSBURGH, July 13, 2011 – Today, researchers from two major HIV prevention trials announced favorable results of an approach called oral pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. One of these trials, the Partners PrEP Study, has provided the strongest evidence yet of PrEP's effectiveness.

Information from both studies will need to be fully evaluated before it can be determined what impact they will have on another major trial that is ongoing. Investigators for VOICE – Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic, and the study's sponsor, the National Institute ...

Pivotal study in Africa finds that HIV medications prevent HIV infection

2011-07-14

In a result that will fundamentally change approaches to HIV prevention in Africa, an international study has demonstrated that individuals at high risk for HIV infection who took a daily tablet containing an HIV medication – either the antiretroviral medication tenofovir or tenofovir in combination with emtricitabine – experienced significantly fewer HIV infections than those who received a placebo pill. These findings are clear evidence that this new HIV prevention strategy, called pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP), substantially reduces HIV infection risk.

The study ...

Wind-turbine placement produces tenfold power increase, Caltech researchers say

2011-07-14

PASADENA, Calif.—The power output of wind farms can be increased by an order of magnitude—at least tenfold—simply by optimizing the placement of turbines on a given plot of land, say researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) who have been conducting a unique field study at an experimental two-acre wind farm in northern Los Angeles County.

A paper describing the findings—the results of field tests conducted by John Dabiri, Caltech professor of aeronautics and bioengineering, and colleagues during the summer of 2010—appears in the July issue of the ...

Separated for 20 million years: Blind beetle from Bulgarian caves clarifies questions

2011-07-14

One of the smallest ever cave-dwelling ground beetles (Carabidae), has recently been discovered in two caves in the Rhodopi Mountains, Bulgaria, and described under the name Paralovricia beroni. The beetle is completely blind and is only 1.8-2.2 mm long. The study was published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

"When we saw this beetle for first time, it became immediately clear that it belongs to a genus and species unknown to science. Moreover, its systematic position within the family of Carabidae remained unclear for several years. After a careful study of its closest ...

UAB researchers present a study on the psychological adaptation of adopted children

2011-07-14

Over 4,000 international adoptions take place in Spain every year. Although the process of adaptation of these children is very similar to that of those living with their biological parents, some studies show that they are more prone to being hyperactive, to having behavioural problems, a low self-esteem and doing poorly in school. A group of researchers at UAB carried out a psychological study aimed at examining adaptation among adopted children with a sample of 52 children from different countries aged 6 to 11, and a control group of 44 non adapted children. Countries ...

Localized reactive badger culling raises bovine tuberculosis risk, new analysis confirms

2011-07-14

Localised badger culling in response to bovine tuberculosis (TB) outbreaks increases the risk of infection in nearby herds, according to a new analysis.

The study, by researchers at the Medical Research Council Centre for Outbreak Analysis and Modelling at Imperial College London, is published today in the Royal Society journal Biology Letters.

The findings come as the Government prepares to decide whether to license farmers to organise the widespread culling of badgers over areas of 150 square kilometres or more in western England.

Bovine TB is a major animal health ...

One-third of central Catalan coast is very vulnerable to storm impact

2011-07-14

Researchers from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC) have developed a method for evaluating the vulnerability of coastal regions to the impact of storms. The method, which has been applied on the Catalan coastline, shows that one-third of the region's coasts have a high rate of vulnerability to flooding, while 20% are at risk of erosion.

"Until now there was no tool for evaluating coastal storm vulnerability that could quantify the processes and the probabilities of these events occurring. This is why we have developed a method to allow coastal managers – the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

[Press-News.org] Carnegie Mellon and Princeton neuroscientists uncover neural mechanisms of object recognitionFindings will force researchers to rethink basic assumptions of visual neuroscience