(Press-News.org) Researchers at Emory and Georgia Tech have developed a method for predicting which areas of the coronary arteries will develop more atherosclerotic plaque over time, based on intracoronary ultrasound and blood flow measurements.

The method could help doctors identify "vulnerable plaque," unstable plaque that is likely to cause a heart attack or stroke. It involves calculating shear stress, or how hard the blood tugs on the walls of the arteries, based on the geometry of the arteries and how fast the blood is moving.

The results were posted online this week in the journal Circulation, published by the American Heart Association. The lead author is Habib Samady, MD, professor of medicine and director of interventional cardiology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Most people who have heart attacks do not have plaques in their arteries that bulge out and obstruct blood flow beforehand. Instead, the plaques in their arteries crack and spill open, leading to a clot. Samady says his team's ultimate aim is to try to figure out where that will happen.

Cardiology researchers studying arteries in isolation or in animals have long seen a link between branches in the arteries, disturbances in blood flow, and where atherosclerosis develops. The challenge was to translate observations from the laboratory to imaging the heart within a live person, he says.

"It's like looking at a river and predicting where sediment will accumulate," he says. "It sounds obvious, but it's hard to do it for every nook and cranny in the coronary arteries."

The Emory/Georgia Tech study was the largest published investigation of shear stress and plaque progression in humans so far, and the first to examine people with significant coronary artery disease. Doctors examined 20 patients in Emory University Hospital's catheterization laboratory between December 2007 and January 2009. They were being examined because they had abnormal exercise EKGs or stable chest pain. The patients' coronary arteries were examined by intracoronary ultrasound and Doppler guide wire before and after six months of therapy with atorvastatin (Lipitor).

To model shear stress, Samady, assistant professor Michael McDaniel, MD, and postdoctoral fellow Parham Eshtehardi, MD, teamed up with Jin Suo and Don Giddens, experts in fluid mechanics at Georgia Tech. The patients' arteries were divided into more than 100 segments each, and the shear stress was calculated for each one. Ultrasound allowed the researchers to estimate the size and composition of the plaques in each segment before and after the six-month period.

"Some atherosclerotic plaque appears to develop in a steady progression, and in other places, it develops in fits and spurts. These areas exist within the same patient and the same artery," Samady says. "Our thinking is that the places where plaque develops in more fits and spurts may lead to the rupture of plaque, leading to a clot that blocks blood flow. In contrast, the places where you have steady progression may be more stable, as long as there is a fibrous covering that is thick enough."

Analyzing each segment, the overall area of the plaque increased and the core of the plaque grew larger in places where shear stress was especially low. In places where the shear stress was high, there was shrinking of the fibrous covering of the plaque and expansion of lipid necrotic core and dense calcified areas.

"High shear stress leads to regression, which you might think is good, but there are some bad actors that may lead to plaque rupture," he says. "What's new here is that we're seeing the detrimental effects of both low and high shear stress."

The data also shows that arterial plaques can grow despite anti-cholesterol therapy with statins, the current standard of care. To really gauge whether plaque in a certain spot is going to be dangerous, Samady says doctors would need to look at outcomes in more patients over a longer time frame.

"The dream is to predict which spot is vulnerable, and use that to guide treatment with drugs and interventions like stents," he says.

For the present, the shear stress-based method can be used to monitor patients' progress and determine how well treatment is working. Samady says ultrasound and blood flow measurements could be combined with a newer technique called optical coherence tomography for better resolution and more information.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, Pfizer Inc., and Volcano Therapeutics.

Reference:

H. Samady, P. Eshtehardi, M.C. McDaniel, J. Suo, S.S. Dhawan, C. Maynard, L.H. Timmins, A.A. Quyyumi and D.P. Giddens. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation (2011 Jul 25). Epub ahead of print.

END

New research raises troubling concerns about the use of aggressive drug therapies to treat a wide range of diseases such as MRSA, C. difficile, malaria, and even cancer.

"The universally accepted strategy of aggressive medication to kill all targeted disease pathogens has the problematic consequence of giving any drug-resistant disease pathogens that are present the greatest possible evolutionary advantage," says Troy Day, one of the paper's co-authors and Canada Research Chair in Mathematical Biology at Queen's.

The researchers note that while the first aim of a drug ...

Measuring the levels of a natural body chemical may allow doctors to reduce the duration of antibiotic use and improve the health outcomes of critically ill patients.

"Infection is a common and expensive complication of critical illness and we're trying to find ways to improve the outcomes of sick, elderly patients and, at the same time, reduce health care costs," says Daren Heyland, a professor of Medicine at Queen's, director of the Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital, and scientific director of the Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network.

Prolonged ...

New Rochelle, NY, August 3, 2011—Positive activity interventions (PAIs) offer a safe, low-cost, and self-administered approach to managing depression and may offer hope to individuals with depressive disorders who do not respond or have access to adequate medical therapy, according to a comprehensive review article in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, a peer-reviewed journal published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. The article, "Delivering Happiness: Translating Positive Psychology Intervention Research for Treating Major and Minor Depressive Disorders" ...

In the months after the April 16, 2007, shootings at Virginia Tech, two professors administered a survey to assess posttraumatic stress among students. The findings have been published in the July 18, 2011 issue of the Journal of Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, published by the American Psychological Association.

According to researchers Michael Hughes, professor of sociology in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, and Russell T. Jones, professor of psychology in the College of Science, 15.4 percent of Virginia Tech students experienced ...

When we make plans that will change a natural environment — whether it's building a new shopping mall or planting a new forest — surveyors dutifully assess the environmental risks to plant and animal life in the region. But what's environmentally good for one area may be an environmental disaster for an adjacent one, a Tel Aviv University researcher cautions.

When displaced by these projects, indigenous species migrate to neighboring habitats, says Guilad Friedemann, a PhD student at TAU's Department of Zoology in the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences. This has ...

People spend 3 billion hours a week playing videogames but little is known scientifically about why they are actually fun in the first place.

The vast majority of research into videogames has concentrated on the possible harmful effects of playing videogames, ignoring the simple question of why people actually want to play them.

But new research led by scientists at the University of Essex sheds some light on the appeal of videogames and why millions of people around the world find playing them so much fun.

The study investigated the idea that many people enjoy playing ...

Many medical devices, ranging from artificial hip joints to dentures and catheters, become sites for unwelcome guests -- complex communities of microbial pathogens called biofilms that are resistant to the human immune system and antibiotics, thus proving a serious threat to human health.

However, researchers may have a new way of looking at biofilms, thanks to a study conducted by University of Iowa biologist David Soll and his colleagues published in the Aug. 2 issue of the online, open access journal PLoS Biology.

Previously, researchers believed that each pathogen ...

This press release is available in Spanish.

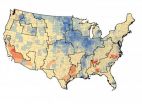

Rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels can reverse the drying effects of predicted higher temperatures on semi-arid rangelands, according to a study published today in the scientific journal Nature by a team of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and university scientists.

Warmer temperatures increase water loss to the atmosphere, leading to drier soils. In contrast, higher CO2 levels cause leaf stomatal pores to partly close, lessening the amount of water vapor that escapes and the amount of water plants draw from soil. ...

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — A Mayo Clinic orthopedic surgeon suspects that the nagging pain and inflammation that women can experience in their knees may be different from what men encounter, and she has been chosen to lead a novel U.S.-Canadian study to explore the question. The Society for Women's Health Research (SWHR) and its Interdisciplinary Studies in Sex-Differences (ISIS) Network on Musculoskeletal Health has awarded a group of researchers a $127,000 grant to lead a pilot project to understand whether biological differences between men and women affect the incidence and ...

RICHLAND, Wash. – Today, farming often involves transporting crops long distances so consumers from Maine to California can enjoy Midwest corn, Northwest cherries and other produce when they are out of season locally. But it isn't just the fossil fuel needed to move food that contributes to agriculture's carbon footprint.

New research published in the journal Biogeosciences provides a detailed account of how carbon naturally flows into and out of crops themselves as they grow, are harvested and are then eaten far from where they're grown. The paper shows how regions that ...