(Press-News.org) The work of molecular biologist Joseph M. Miano, Ph.D., and clinician Craig Benson, M.D., seems worlds apart: Miano helps head the Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute and Benson is chief resident of the combined Internal Medicine and Pediatrics program at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Though the chance of their professional paths crossing was highly unlikely, shared enthusiasm, intense curiosity and a little detective work led to a unique collaboration and important new insights on the inner workings of the human genome.

Together, Miano and Benson created a model resource that not only identifies but also outlines the function of some of the most common mutations in the human genome. At a time when research linking genetic mutations to disease risk is booming – a result of the sequencing of the human genome in the early 2000's – the clinician-scientist team is pursuing what they think is an even more significant path: They are zeroing in on how certain mutations actually work, information they believe will help guide the development of new prevention and treatment options.

"It is valuable to know when someone is at greater risk for disease, but that information doesn't explain the mechanism of disease or give any insight into what we might be able to do therapeutically for patients," said Benson, lead author of the new study published in Physiological Genomics. "Our goal is to help scientists figure out what's happening at the molecular level so they can determine the best way to potentially treat disease. As a clinician, that is what is most important for me, understanding how we can improve patient care."

Benson, who came to Rochester for medical school in 2003, stayed for a medicine-pediatrics residency and participated in the program's research track, which allowed him some time to conduct research. With an undergraduate degree in business and computer information systems and a master's degree in health informatics, he was eager to study bioinformatics and genomics. Not sure where to start, given the Medical Center's vast research enterprise, he launched a broad internal search to find a program or person to pursue.

Miano, a self-described "gene jock" whose lab focuses on finding and describing hidden information within the human genome, popped up in the search. Opportunely, he was in great need of someone with a computer background to scour databases full of information on the genome to help him advance his research. For years Miano wanted to create the database the pair recently unveiled, but it wasn't until Benson approached him that the idea really got off the ground.

"To have Craig, a young resident, reach out to me and say, 'I'm interested and have the skills you need,' was a huge blessing," said Miano, a faculty member in the School of Medicine and Dentistry for the past 11 years. "While we don't see partnerships like this every day, it is a really beautiful collaboration that I hope the University can replicate more in the future."

Once connected, the pair honed in on mutations in the human genome that affect a critical "lock and key" combination that scientists believe is responsible for turning on or off a wide range of genes that create many of the proteins we are made of. When the "lock" – a segment of DNA known as the CArG box – and the "key" – a protein known as SRF – come together or bind, they unlock the ability of a cell to turn on a gene.

While there are thousands of genetic lock and key combinations that turn genes on or off, the authors chose to study this particular one because, according to Miano, it is absolutely vital for life. "It is found in every organ system, from the heart and eyes, to the skin and bones. Studies suggest it may regulate up to 20 percent of our protein-creating genes, which is a very large collection of genes."

Benson spearheaded the first segment of the study, identifying where the lock and key are located within the vast section of the genome that scientists know the least about – the 98.5 percent that does not create proteins. He developed a computer program and, using a publicly available database derived from the Human Genome Project, scanned about five percent of the genome for the locks. Once he identified these sites – more than 8,000 – he created a similar program to look for mutations within these locks. Ultimately, he found 115 sites containing mutations.

Next, Miano stepped in to analyze how these mutations affect the lock and key. Experiments in his laboratory using human cells revealed that when a mutation is present, the lock and key is weaker; it doesn't fit together or bind as well as when it is free of any mutations. Though they didn't study gene expression, the authors infer that an altered lock and key likely changes how strongly a gene is turned on or suppressed, which could influence disease.

"Our findings are important because if a scientist discovers that one of the mutations we identified and tested is linked to a particular disease, our database will immediately provide a deeper understanding of the mutation and consequently a window into why the disease may be happening," noted Miano.

Miano and Benson don't know of any diseases caused by the mutations they identified yet, but Benson did discover that some of the mutations are linked to conditions such as type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke. Further study is needed to see if and how the mutations play a role.

The two plan to continue their work together, even when Benson starts a cardiology fellowship program at Harvard next year. They credit their successful collaboration to a mutual passion for the research, flexibility and understanding.

"Joe recognized and appreciated the limitations I had in taking on this research, because my primary responsibility was as a clinician. He understood that I couldn't be in the lab every day, but at the same time he knew I was committed," said Benson, who has spent the past four years practicing at the Culver Medical Center, part of the University's Center for Primary Care. "The attending physicians in my program were also very encouraging when it came to my research; I couldn't imagine trying to do this without their support."

INFORMATION:

The current work was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health. In addition to Miano and Benson, Qian Zhou, B.M., M.S. and Xiaochun Long, Ph.D., from the Miano Lab contributed to the research.

END

Critical Information Network (CiNet), LLC, announces the release of its newly updated Electrical 1 training series designed to help companies improve the electrical maintenance practices of workers and meet the demands of today's busy training manager.

According to OSHA and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), electrical accidents and the resulting fires cause millions of dollars in damages, countless injuries and life threatening workplace events every year. The tragedy is that many of these could have been avoided by simple maintenance repairs supported ...

(WASHINGTON, August 11, 2011) – According to a study published in Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), researchers have reported that administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), a drug that releases stem cells from the bone marrow into the blood, is unlikely to put healthy stem cell donors at risk for later development of abnormalities involving loss or gains of chromosomes that have been linked to hematologic disorders such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

G-CSF therapy is given to healthy ...

While many Britons enjoyed the recent heatwave, taking the chance to lie back and top up their tans, for others it only served to heighten their fears of damp armpits and clammy hands.

As a result, Transform Cosmetic Surgery Group recorded a 45% surge in enquiries into use of BOTOX injections a treatment for excessive sweating over a three-day period of the heatwave as the nation become more perspiration-conscious.

Known as hyperhidrosis, the condition sees sweat glands become overactive, something often made worse during periods of hot weather. During the procedure, ...

By isolating cells from patients' spinal tissue within a few days after death, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have developed a new model of the paralyzing disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). They found that during the disease, cells called astrocytes become toxic to nerve cells – a result previously found in animal models but not in humans. The new model could be used to investigate many more questions about ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

ALS can run in families, but in the majority of cases, it is sporadic, with no known ...

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– Viruses fill the ocean and have a significant effect on ocean biology, specifically marine microbiology, according to a professor of biology at UC Santa Barbara and his collaborators.

Craig A. Carlson, professor with UCSB's Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, is the senior author of a study of marine viruses published this week by the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal, of the Nature Publishing Group.

The new findings, resulting from a decade of research, reveal striking recurring patterns of marine virioplankton ...

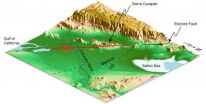

PASADENA, Calif.— Like scars that remain on the skin long after a wound has healed, earthquake fault lines can be traced on Earth's surface long after their initial rupture. Typically, this line of intersection between the area where the fault slips and the ground is more complicated at the surface than at depth. But a new study of the April 4, 2010, El Mayor–Cucapah earthquake in Mexico reveals a reversal of this trend. While the fault involved in the event appeared to be superficially straight, the fault zone is warped and complicated at depth.

The study—led by researchers ...

MADISON, WI, JULY 11, 2011 -- Although phosphorus is an essential nutrient for all life forms, essential amounts of the chemical element can cause water quality problems in rivers, lakes, and coastal zones. High concentrations of phosphorus in aquatic ecosystems are often associated with human activities in the surrounding area, such as agriculture and urban development. However, relationships between specific human sources of phosphorus and phosphorus concentrations in aquatic ecosystems are yet to be understood. Establishing these relationships could allow for the development, ...

WHAT:Pyrazinamide has been used in combination with other drugs as a first-line treatment for people with tuberculosis (TB) since the 1950s, but exactly how the drug works has not been well understood. Now, researchers have discovered a key reason why the drug effectively shortens the required duration of TB therapy. The finding potentially paves the way for the development of new drugs that can help eliminate TB in an infected individual even more rapidly. The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National ...

In 1991, Carl Lewis was both the fastest man on earth and a profound long jumper, perhaps the greatest track-and-field star of all time in the prime of his career. On June 14th of that year, however, Carl Lewis was human. Leroy Burrell blazed through the 100-meters, besting him by a razor-thin margin of three-hundredths of a second. In the time it takes the shutter to capture a single frame of video, Lewis's three-year-old world record was gone.

In a paper just published in the journal Neuron, a team at the Stanford School of Engineering, led by electrical engineers Krishna ...

PITTSBURGH—The transport system inside living cells is a well-oiled machine with tiny protein motors hauling chromosomes, neurotransmitters and other vital cargo around the cell. These molecular motors are responsible for a variety of critical transport jobs, but they are not always on the go. They can put themselves into "energy save mode" to conserve cellular fuel and, as a consequence, control what gets moved around the cell, and when.

A new study from Carnegie Mellon University and the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research published in the Aug. 12 issue of Science ...