(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C.-- In a first ever demonstration of a two-way interaction between a primate brain and a virtual body, two monkeys trained at the Duke University Center for Neuroengineering learned to employ brain activity alone to move an avatar hand and identify the texture of virtual objects.

"Someday in the near future, quadriplegic patients will take advantage of this technology not only to move their arms and hands and to walk again, but also to sense the texture of objects placed in their hands, or experience the nuances of the terrain on which they stroll with the help of a wearable robotic exoskeleton," said Miguel Nicolelis, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurobiology at Duke University Medical Center and co-director of the Duke Center for Neuroengineering, who was senior author of the study.

Without moving any part of their real bodies, the monkeys used their electrical brain activity to direct the virtual hands of an avatar to the surface of virtual objects and, upon contact, were able to differentiate their textures.

Although the virtual objects employed in this study were visually identical, they were designed to have different artificial textures that could only be detected if the animals explored them with virtual hands controlled directly by their brain's electrical activity.

The texture of the virtual objects was expressed as a pattern of minute electrical signals transmitted to the monkeys' brains. Three different electrical patterns corresponded to each of three different object textures.

Because no part of the animal's real body was involved in the operation of this brain-machine-brain interface (BMBI), these experiments suggest that in the future patients severely paralyzed due to a spinal cord lesion may take advantage of this technology, not only to regain mobility, but also to have their sense of touch restored, said Nicolelis, who was senior author of the study published in the journal Nature on Oct. 5.

"This is the first demonstration of a brain-machine-brain interface that establishes a direct, bidirectional link between a brain and a virtual body," Nicolelis said. "In this BMBI, the virtual body is controlled directly by the animal's brain activity, while its virtual hand generates tactile feedback information that is signaled via direct electrical microstimulation of another region of the animal's cortex."

"We hope that in the next few years this technology could help to restore a more autonomous life to many patients who are currently locked in without being able to move or experience any tactile sensation of the surrounding world," Nicolelis said.

"This is also the first time we've observed a brain controlling a virtual arm that explores objects while the brain simultaneously receives electrical feedback signals that describe the fine texture of objects 'touched' by the monkey's newly acquired virtual hand," Nicolelis said. "Such an interaction between the brain and a virtual avatar was totally independent of the animal's real body, because the animals did not move their real arms and hands, nor did they use their real skin to touch the objects and identify their texture. It's almost like creating a new sensory channel through which the brain can resume processing information that cannot reach it anymore through the real body and peripheral nerves."

The combined electrical activity of populations of 50-200 neurons in the monkey's motor cortex controlled the steering of the avatar arm, while thousands of neurons in the primary tactile cortex were simultaneously receiving continuous electrical feedback from the virtual hand's palm that let the monkey discriminate between objects, based on their texture alone.

"The remarkable success with non-human primates is what makes us believe that humans could accomplish the same task much more easily in the near future," Nicolelis said.

It took one monkey only four attempts and another nine attempts before they learned how to select the correct object during each trial. Several tests demonstrated that the monkeys were actually sensing the object and not selecting them randomly.

The findings provide further evidence that it may be possible to create a robotic exoskeleton that severely paralyzed patients could wear in order to explore and receive feedback from the outside world, Nicolelis said. Such an exoskeleton would be directly controlled by the patient's voluntary brain activity in order to allow the patient to move autonomously. Simultaneously, sensors distributed across the exoskeleton would generate the type of tactile feedback needed for the patient's brain to identify the texture, shape and temperature of objects, as well as many features of the surface upon which they walk.

This overall therapeutic approach is the one chosen by the Walk Again Project, an international, non-profit consortium, established by a team of Brazilian, American, Swiss, and German scientists, which aims at restoring full body mobility to quadriplegic patients through a brain-machine-brain interface implemented in conjunction with a full-body robotic exoskeleton.

The international scientific team recently proposed to carry out its first public demonstration of such an autonomous exoskeleton during the opening game of the 2014 FIFA Soccer World Cup that will be held in Brazil.

###

Other authors include Joseph E. O'Doherty, Mikhail A. Lebedev, Peter J. Ifft, Katie Z. Zhuang, all from the Duke University Center for Neuroengineering and Solaiman Shokur, and Hannes Bleuler from the Ecole Polytechnic Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), in Lausanne, Switzerland.

This work was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Monkeys 'move and feel' virtual objects using only their brains

2011-10-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ross-Simons Announces its Annual Holiday Jewelry Sweepstakes

2011-10-06

Ross-Simons is excited to announce an online jewelry sweepstakes, co-sponsored by More, the magazine for women of style and substance. The "Gotta Have Bling Sweepstakes" will give away $10,000 worth of fine jewelry to three very lucky winners. Contestants are invited to enter online at www.ross-simons.com/sweeps to win the following prizes:

- One Grand Prize: $5,000 Ross-Simons jewelry shopping spree

- One First Prize: $3,000 Ross-Simons jewelry shopping spree

- One Second Prize: $2,000 Ross-Simons jewelry shopping spree

An Unprecedented Jewelry Extravaganza

Darrell ...

Lack of compensation for human egg donors could stall recent breakthroughs in stem cell research

2011-10-06

Women donating their eggs for use in fertility clinics are typically financially compensated for the time and discomfort involved in the procedure. However, guidelines established by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in 2005 state that women who donate their eggs for use in stem cell research should not be compensated, although the procedures they undergo are the same. In the October 7th issue of Cell Stem Cell, researchers at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) and the Department of Bioethics at Case Western Reserve University argue that this lack of compensation ...

Health Affairs article focuses on health care disparities facing people with disabilities

2011-10-06

Two decades after the Americans with Disabilities Act went into effect, people with disabilities continue to face difficulties meeting major social needs, including obtaining appropriate access to health care facilities and services. In an article in the October issue of Health Affairs, Lisa Iezzoni, MD, director of the Mongan Institute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital, analyzes available information on disparities affecting people with disabilities and highlights barriers that continue to restrict their access to health services.

"A lot of attention ...

Progression of lung fibrosis blocked in mouse model

2011-10-06

A study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine may lead to a way to prevent the progression, or induce the regression, of lung injury that results from use of the anti-cancer chemotherapy drug Bleomycin. Pulmonary fibrosis caused by this drug, as well as Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) from unknown causes, affect nearly five million people worldwide. No therapy is known to improve the health or survival of patients.

Their research shows that the RSK-C/EBP-Beta phosphorylation pathway may contribute to the development of lung injury ...

Novel Stanford math formula can predict success of certain cancer therapies

2011-10-06

STANFORD, Calif. — Carefully tracking the rate of response of human lung tumors during the first weeks of treatment can predict which cancers will undergo sustained regression, suggests a new study by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The finding was made after scientists gained a new insight into therapies that target cancer-causing genes: They are successful not because they cause cell death directly, but instead because they slow the rate of tumor cell division. In other words, squelching messages promoting rampant cell growth allows already ...

Distribution atlas of butterflies in Europe

2011-10-06

Halle/Saale and Berlin. Scientists present the largest distribution data compilation ever on butterflies of an entire continent. The Germany based Society for the Conservation of Butterflies and Moths GfS ("Gesellschaft für Schmetterlingsschutz"), the German Nature Conservation Association NABU ("Naturschutzbund Deutschland") and the Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) are delighted to announce the publication of the „Distribution Atlas of Butterflies in Europe".

The atlas was initiated by Otakar Kudrna and is a result of the joint efforts of a team of authors, ...

Immune mechanism blocks inflammation generated by oxidative stress

2011-10-06

Conditions like atherosclerosis and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) -- the most common cause of blindness among the elderly in western societies -- are strongly linked to increased oxidative stress, the process in which proteins, lipids and DNA damaged by oxygen free radicals and related cellular waste accumulate, prompting an inflammatory response from the body's innate immune system that results in chronic disease.

In the October 6, 2011 issue of Nature, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, as part of an international collaborative ...

Survival increased in early stage breast cancer after treatment with herceptin and chemo

2011-10-06

Treating women with early stage breast cancer with a combination of chemotherapy and the molecularly targeted drug Herceptin significantly increases survival in patients with a specific genetic mutation that results in very aggressive disease, a researcher with UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center reported Wednesday.

The study also found that a regimen without the drug Adriamycin, an anthracycline commonly used as a mainstay to treat breast cancer but one that, especially when paired with Herceptin, can cause permanent heart damage, was comparable to a regimen ...

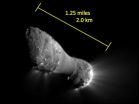

First comet found with ocean-like water

2011-10-06

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- New evidence supports the theory that comets delivered a significant portion of Earth's oceans, which scientists believe formed about 8 million years after the planet itself.

The findings, which involve a University of Michigan astronomer, are published Oct. 5 online in Nature.

"Life would not exist on Earth without liquid water, and so the questions of how and when the oceans got here is a fundamental one," said U-M astronomy professor Ted Bergin, "It's a big puzzle and these new findings are an important piece."

Bergin is a co-investigator on ...

Women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in the womb face increased cancer risk

2011-10-06

A large study of the daughters of women who had been given DES, the first synthetic form of estrogen, during pregnancy has found that exposure to the drug while in the womb (in utero) is associated with many reproductive problems and an increased risk of certain cancers and pre-cancerous conditions. The results of this analysis, conducted by researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health, and collaborators across the country, were published Oct. 6, 2011, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Beginning in 1940, diethylstilbestrol, ...