(Press-News.org) When an international collaboration of physicists came up with a result that punched a hole in Einstein's theory of special relativity and couldn't find any mistakes in their work, they asked the world to take a second look at their experiment.

Responding to the call was Ramanath Cowsik, PhD, professor of physics in Arts & Sciences and director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Online and in the December 24 issue of Physical Review Letters, Cowsik and his collaborators put their finger on what appears to be an insurmountable problem with the experiment.

The OPERA experiment, a collaboration between the CERN physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland, and the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso (LNGS) in Gran Sasso, Italy, timed particles called neutrinos traveling through Earth from the physics laboratory CERN to a detector in an underground laboratory in Gran Sasso, a distance of some 730 kilometers, or about 450 miles.

OPERA reported online and in Physics Letters B in September that the neutrinos arrived at Gran Sasso some 60 nanoseconds sooner than they would have arrived if they were traveling at the speed of light in a vacuum.

Neutrinos are thought to have a tiny, but nonzero, mass. According to the theory of special relativity, any particle that has mass may come close to but cannot quite reach the speed of light. So superluminal (faster than light) neutrinos should not exist.

The neutrinos in the experiment were created by slamming speeding protons into a stationary target, producing a pulse of pions — unstable particles that were magnetically focused into a long tunnel where they decayed in flight into muons and neutrinos.

The muons were stopped at the end of the tunnel, but the neutrinos, which slip through matter like ghosts through walls, passed through the barrier and disappeared in the direction of Gran Sasso.

In their journal article, Cowsik and an international team of collaborators took a close look at the first step of this process. "We have investigated whether pion decays would produce superluminal neutrinos, assuming energy and momentum are conserved," he says.

The OPERA neutrinos had energies of about 17 gigaelectron volts. "They had a lot of energy but very little mass," Cowsik says, "so they should go very fast." The question is whether they went faster than the speed of light.

"We've shown in this paper that if the neutrino that comes out of a pion decay were going faster than the speed of light, the pion lifetime would get longer, and the neutrino would carry a smaller fraction of the energy shared by the neutrino and the muon," Cowsik says.

"What's more," he says, "these difficulties would only increase as the pion energy increases.

"So we are saying that in the present framework of physics, superluminal neutrinos would be difficult to produce," Cowsik explains.

In addition, he says, there's an experimental check on this theoretical conclusion. The creation of neutrinos at CERN is duplicated naturally when cosmic rays hit Earth's atmosphere.

A neutrino observatory called IceCube detects these neutrinos when they collide with other particles generating muons that leave trails of light flashes as they plow into the thick, clear ice of Antarctica.

"IceCube has seen neutrinos with energies 10,000 times higher than those the OPERA experiment is creating," Cowsik says.."Thus, the energies of their parent pions should be correspondingly high. Simple calculations, based on the conservation of energy and momentum, dictate that the lifetimes of those pions should be too long for them ever to decay into superluminal neutrinos.

"But the observation of high-energy neutrinos by IceCube indicates that these high-energy pions do decay according to the standard ideas of physics, generating neutrinos whose speed approaches that of light but never exceeds it.

Cowsik's objection to the OPERA results isn't the only one that has been raised.

Physicists Andrew G. Cohen and Sheldon L. Glashow published a paper in Physical Review Letters in October showing that superluminal neutrinos would rapidly radiate energy in the form of electron-positron pairs.

"We are saying that, given physics as we know it today, it should be hard to produce any neutrinos with superluminal velocities, and Cohen and Glashow are saying that even if you did, they'd quickly radiate away their energy and slow down," Cowsik says.

"I have very high regard for the OPERA experimenters," Cowsik adds. "They got faster-than-light speeds when they analyzed their data in March, but they struggled for months to eliminate possible errors in their experiment before publishing it.

"Not finding any mistakes," Cowsik says, "they had an ethical obligation to publish so that the community could help resolve the difficulty. That's the demanding code physicists live by," he says.

INFORMATION:

Pions don't want to decay into faster-than-light neutrinos, study finds

Major speed bump in the path of a startling result announced in September

2011-12-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A radar for ADAR: Altered gene tracks RNA editing in neurons

2011-12-27

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To track what they can't see, pilots look to the green glow of the radar screen. Now biologists monitoring gene expression, individual variation, and disease have a glowing green indicator of their own: Brown University biologists have developed a "radar" for tracking ADAR, a crucial enzyme for editing RNA in the nervous system.

The advance gives scientists a way to view when and where ADAR is active in a living animal and how much of it is operating. In experiments in fruit flies described in the journal Nature Methods, the researchers ...

New synthetic molecules treat autoimmune disease in mice

2011-12-27

A team of Weizmann Institute scientists has turned the tables on an autoimmune disease. In such diseases, including Crohn's and rheumatoid arthritis, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's tissues. But the scientists managed to trick the immune systems of mice into targeting one of the body's players in autoimmune processes, an enzyme known as MMP9. The results of their research appear today in Nature Medicine.

Prof. Irit Sagi of the Biological Regulation Department and her research group have spent years looking for ways to home in on and block members of the ...

Faster, more accurate, more sensitive

2011-12-27

Lightning fast and yet highly sensitive: HHblits is a new software tool for protein research which promises to significantly improve the functional analysis of proteins. A team of computational biologists led by Dr. Johannes Söding of LMU's Genzentrum has developed a new sequence search method to identify proteins with similar sequences in databases that is faster and can discover twice as many evolutionarily related proteins as previous methods. From the functional and structural properties of the identified proteins conclusions can then be drawn on the properties of ...

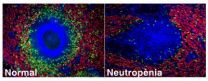

Discovered the existence of neutrophils in the spleen

2011-12-27

This release is available in Spanish.

Barcelona, 23rd of December 2011.- For the first time, it has been discovered that neutrophils exist in the spleen without there being an infection. This important finding made by the research group on the Biology of B Cells of IMIM (Hospital del Mar Research Institute) in collaboration with researchers from Mount Sinai in New York, has also made it possible to determine that these neutrophils have an immunoregulating role.

Neutrophils are the so-called cleaning cells, since they are the first cells to migrate to a place ...

Study links quality of mother-toddler relationship to teen obesity

2011-12-27

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The quality of the emotional relationship between a mother and her young child could affect the potential for that child to be obese during adolescence, a new study suggests.

Researchers analyzed national data detailing relationship characteristics between mothers and their children during their toddler years. The lower the quality of the relationship in terms of the child's emotional security and the mother's sensitivity, the higher the risk that a child would be obese at age 15 years, according to the analysis.

Among those toddlers who had the lowest-quality ...

Memo to pediatricians: Allergy tests are no magic bullets for diagnosis

2011-12-27

An advisory from two leading allergists, Robert Wood of the Johns Hopkins Children's Center and Scott Sicherer of Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, urges clinicians to use caution when ordering allergy tests and to avoid making a diagnosis based solely on test results.

In an article, published in the January issue of Pediatrics, the researchers warn that blood tests, an increasingly popular diagnostic tool in recent years, and skin-prick testing, an older weapon in the allergist's arsenal, should never be used as standalone diagnostic strategies. These tests, Sicherer ...

Study uncovers a molecular 'maturation clock' that modulates branching architecture in tomato plants

2011-12-27

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – The secret to pushing tomato plants to produce more fruit might not lie in an extra dose of Miracle-Gro. Instead, new research from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) suggests that an increase in fruit yield might be achieved by manipulating a molecular timer or so-called "maturation clock" that determines the number of branches that make flowers, called inflorescences.

"We have found that a delay in this clock causes more branching to occur in the inflorescences, which in turn results in more flowers and ultimately, more fruits," says CSHL ...

Over 65 million years North American mammal evolution has tracked with climate change

2011-12-27

PROVIDENCE, R.I. -- History often seems to happen in waves – fashion and musical tastes turn over every decade and empires give way to new ones over centuries. A similar pattern characterizes the last 65 million years of natural history in North America, where a novel quantitative analysis has identified six distinct, consecutive waves of mammal species diversity, or "evolutionary faunas." What force of history determined the destiny of these groupings? The numbers say it was typically climate change.

"Although we've always known in a general way that mammals respond ...

Sunlight and bunker oil a fatal combination for Pacific herring

2011-12-27

The 2007 Cosco Busan disaster, which spilled 54,000 gallons of oil into the San Francisco Bay, had an unexpectedly lethal impact on embryonic fish, devastating a commercially and ecologically important species for nearly two years, reports a new study by the University of California, Davis, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The study, to be published the week of Dec. 26 in the early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that even small oil spills can have a large impact on marine life, and that common chemical ...

Avital Web, Los Angeles SEO Company, is Offering Free Dental SEO Services

2011-12-27

Internet marketing is an important component in the marketing strategy of every business, including dentists. Having a top ranking website is quite essential for bringing in new customers. That is why Avital Web, a top SEO company in Los Angeles, is now offering free dental SEO packages to qualified dentists to help them improve the ranking of their websites.

Competition Fierce for Dental Practices

The family dentistry office barely exists anymore. Between teeth whitening and dental implants, impressive new Invisalign technology and other cosmetic dental practices, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for March 2026

New tools and techniques accelerate gallium oxide as next-generation power semiconductor

Researchers discover seven different types of tension

Report calls for AI toy safety standards to protect young children

VR could reduce anxiety for people undergoing medical procedures

Scan that makes prostate cancer cells glow could cut need for biopsies

Mechanochemically modified biochar creates sustainable water repellent coating and powerful oil adsorbent

New study reveals hidden role of larger pores in biochar carbon capture

Specialist resource centres linked to stronger sense of belonging and attainment for autistic pupils – but relationships matter most

Marshall University, Intermed Labs announce new neurosurgical innovation to advance deep brain stimulation technology

Preclinical study reveals new cream may prevent or slow growth of some common skin cancers

Stanley Family Foundation renews commitment to accelerate psychiatric research at Broad Institute

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1 drugs? New Cleveland Clinic study reveals real world insights

American Meteorological Society responds to NSF regarding the future of NCAR

Beneath Great Salt Lake playa: Scientists uncover patchwork of fresh and salty groundwater

Fall prevention clinics for older adults provide a strong return on investment

People's opinions can shape how negative experiences feel

USC study reveals differences in early Alzheimer’s brain markers across diverse populations

300 million years of hidden genetic instructions shaping plant evolution revealed

High-fat diets cause gut bacteria to enter brain, Emory study finds

Teens and young adults with ADHD and substance use disorder face treatment gap

Instead of tracking wolves to prey, ravens remember — and revisit — common kill sites

Ravens don’t follow wolves to dinner – they remember where the food is

Mapping the lifelong behavior of killifish reveals an architecture of vertebrate aging

Designing for hard and brittle lithium needles may lead to safer batteries

Inside the brains of seals and sea lions with complex vocal behavior learning

Watching a lifetime in motion reveals the architecture of aging

Rapid evolution can ‘rescue’ species from climate change

Molecular garbage on tumors makes easy target for antibody drugs

New strategy intercepts pancreatic cancer by eliminating microscopic lesions before they become cancer

[Press-News.org] Pions don't want to decay into faster-than-light neutrinos, study findsMajor speed bump in the path of a startling result announced in September