(Press-News.org) Archaeologists who interpret Stone Age culture from discoveries of ancient tools and artifacts may need to reanalyze some of their conclusions.

That's the finding suggested by a new study that for the first time looked at the impact of water buffalo and goats trampling artifacts into mud.

In seeking to understand how much artifacts can be disturbed, the new study documented how animal trampling in a water-saturated area can result in an alarming amount of disturbance, says archaeologist Metin I. Eren, a graduate student at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, and one of eight researchers on the study.

In a startling finding, the animals' hooves pushed artifacts as much as 21 centimeters into the ground — a variation that could equate to a difference of thousands of years for a scientist interpreting a site, said Erin. The findings suggest archaeologists should reanalyze some previous discoveries, he said.

"Given that during the Lower and most of the Middle Pleistocene, hominids stayed close to water sources, we cannot help but wonder how prevalent saturated substrate trampling might be, and how it has affected the context, and resulting interpretation, of Paleolithic sites throughout the Old World," conclude the authors in a scientific paper detailing their experiment and its findings.

"Experimental Examination of Animal Trampling Effects on Artifact Movement in Dry and Water Saturated Substrates: A Test Case from South India" has been published online by the Journal of Archaeological Science. For images, additional information and a link to the article, see www.smuresearch.com. The research was recognized as best student poster at the 2010 annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology.

Animal trampling not new; study adds new variable

The idea that animal trampling may reorient artifacts is not new.

"Believe it or not, there have been dozens of trampling experiments in archaeology to see how artifacts may be affected by animals walking over them. These have involved human trampling and the trampling of all sorts of animals, including elephants, in dry sediments," Eren said. "Our trampling experiments in dry sediments, for the most part, mimicked the results of previous experiments."

But this latest study added a new variable to the mix — the trampling of artifacts embedded in ground saturated with water, Eren said.

Researchers from the United States, Britain, Australia and India were inspired to perform the unique experiment while doing archaeological survey work in the Jurreru River Valley in Southern India.

They noticed that peppering the valley floor were hardened hoof prints left from the previous monsoon season, as well as fresh prints along the stream banks. Seeing that the tracks sunk quite deeply into the ground, the researchers began to suspect that stone artifacts scattered on the edges of water bodies could be displaced significantly from their original location by animal trampling.

Early humans drawn to water's edge

"Prehistoric humans often camped near water sources or in areas that receive lots of seasonal rain. When we saw those deep footprints left over from the previous monsoon season, it occurred to us that animal trampling in muddy, saturated sediments might distort artifacts in a different way than dry sediments," Eren said. "Given the importance of artifact context in the interpretation of archaeological sites and age, it seems like an obvious thing to test for, but to our surprise it never had been."

Eren and seven other researchers tested their theory by scattering replicated stone tools over both dry and saturated areas of the valley. They then had water buffalo and goats trample the "sites." Once sufficient trampling occurred, the archaeologists proceeded to excavate the tools, taking careful measurements of where the tools were located and their inclination in the ground.

The researchers found that tools salted on ground saturated with water and trampled by buffalo moved up to 21 centimeters vertically, or a little more than 8 inches. Tools trampled by goats moved up to 16 centimeters vertically, or just over 6 inches.

"A vertical displacement of 21 centimeters in some cases might equal thousands of years when we try to figure out the age of an artifact," Eren said. "This amount of disturbance is more than any previously documented experiment — and certainly more than we anticipated."

A new "diagnostic marker"

Unfortunately for archaeologists who study the Stone Age, artifacts left behind by prehistoric humans do not stay put, said Eren. Over thousands or even millions of years, all sorts of geological or other processes can move artifacts out of place, he said.

The movement distorts the cultural and behavioral information that is contained in the original artifact patterning, what archaeologists call "context." Archaeologists must discern whether artifacts are in their original context, and thus provide reliable information, or if they've been disturbed in some way that biases the interpretation, said Eren, a graduate student in the SMU Department of Anthropology.

Given that artifacts embedded in the ground at vertical angles appear to be a diagnostic marker of trampling disturbance, the researchers concluded that sites with water-saturated sediments should be identified and reanalyzed.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the study include Adam Durant, University of Cambridge; Christina Neudorf, University of Wollongong; Michael Haslam, University of Oxford; Ceri Shipton, Monash University; Janardhana Bora, Karnatak University; Ravi Korisettar, Karnatak University; and Michael Petraglia, University of Oxford. Korisettar and Petraglia are the principal investigators of the archaeological field research in Kurnool, India.

The research was funded by Leverhulme Trust, British Academy, National Science Foundation, Australian Research Council, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, Lockheed Martin Corporation.

SMU is a private university in Dallas where nearly 11,000 students benefit from the national opportunities and international reach of SMU's seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Taking a new look at old digs: Trampling animals may alter Stone Age sites

Study found water buffalo and goats pushed artifacts deep into mud, potentially altering a site's interpretation by thousands of years

2010-09-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

High pressure experiments reproduce mineral structures 1,800 miles deep

2010-09-24

University of California, Berkeley, and Yale University scientists have recreated the tremendous pressures and high temperatures deep in the Earth to resolve a long-standing puzzle: why some seismic waves travel faster than others through the boundary between the solid mantle and fluid outer core.

Below the earth's crust stretches an approximately 1,800-mile-thick mantle composed mostly of a mineral called magnesium silicate perovskite (MgSiO3). Below this depth, the pressures are so high that perovskite is compressed into a phase known as post-perovskite, which comprises ...

Cancer-associated long non-coding RNA regulates pre-mRNA splicing

2010-09-24

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report this month that MALAT1, a long non-coding RNA that is implicated in certain cancers, regulates pre-mRNA splicing – a critical step in the earliest stage of protein production. Their study appears in the journal Molecular Cell.

Nearly 5 percent of the human genome codes for proteins, and scientists are only beginning to understand the role of the rest of the "non-coding" genome. Among the least studied non-coding genes – which are transcribed from DNA to RNA but generally are not translated into proteins – are the long non-coding RNAs ...

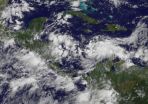

GOES-13 sees tropical depression 15 form in the south-central Caribbean Sea

2010-09-24

The fifteenth tropical depression of the Atlantic Ocean season has formed in the south-central Caribbean Sea, and the GOES-13 satellite captured its swirling mass of clouds and showers in a visible image today. Watches and warnings are already up for Central America.

At 2 p.m. EDT today, Sept. 23, Tropical Depression 15 had maximum sustained winds near 35 mph. It was located about 485 miles east of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, near 13.9 North and 76.2 West. It was moving west at 15 mph, and had a minimum central pressure of 1007 millibars.

The government of Nicaragua ...

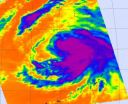

NASA sees important cloud-top temperatures as Tropical Storm Malakas heads for Iwo To

2010-09-24

NASA's Aqua satellite has peered into the cloud tops of Tropical Storm Malakas and derived just how cold they really are, giving an indication to forecasters of the strength of the storm.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder instrument, known as AIRS has the ability to determine cloud top and sea surface temperatures from its position in space aboard NASA's Aqua satellite. Cloud top temperatures help forecasters know if a storm is powering up or powering down.

When cloud top temperatures get colder it means that they're getting higher into the atmosphere which means the ...

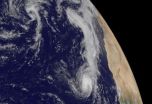

NASA satellites help see ups and downs ahead for Depression Lisa

2010-09-24

Tropical Depression Lisa has had a struggle, and it appears that she's in for more of the same.

Infrared satellite imagery from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite shows that the convection (rapidly rising air that forms thunderstorms that make up a tropical cyclone) is increasing in Lisa. The convection is becoming a little better organized and stronger which is will make for some heavy rainfall over the northwestern Cape Verde Islands. It's also an indication that she may be strengthening back into a tropical storm today.

That ...

Team of researchers finds possible new genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease

2010-09-24

Researchers have identified a gene that appears to increase a person's risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of the disease. The gene, abbreviated as MTHFD1L, is on chromosome six, and was identified in a genome-wide association study. Details are published September 23 in the journal PLoS Genetics.

The collaborative team of researchers was led by Margaret A. Pericak-Vance, PhD, Director of the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, ...

Earth: Fixing Pakistan's water woes

2010-09-24

Pakistan is facing tremendous water issues. This summer's flooding has left millions of people without homes and without access to clean drinking water. But water issues - both quantity and quality - are not new to this strategically important country. Waterborne diseases account for 30 percent of all deaths in Pakistan, and kill some 250,000 children each year. Per capita water availability in Pakistan is less than one-ninth of what it is in the U.S. And what's more, researchers say if Pakistan doesn't manage its water resources differently, it's going to actually run ...

Robotic arm's big flaw: Patients say it's 'too easy'

2010-09-24

One touch directs a robotic arm to grab objects in a new computer program designed to give people in wheelchairs more independence.

University of Central Florida researchers thought the ease of the using the program's automatic mode would be a huge hit. But they were wrong – many participants in a pilot study didn't like it because it was "too easy."

Most participants preferred the manual mode, which requires them to think several steps ahead and either physically type in instructions or verbally direct the arm with a series of precise commands. They favored the manual ...

Black motorcyclists -- even in helmets -- more likely to die in crashes

2010-09-24

African-American victims of motorcycle crashes were 1.5 times more likely to die from their injuries than similarly injured whites, even though many more of the African-American victims were wearing helmets at the time of injury, according to a new study by Johns Hopkins researchers.

Results of the research revealing these racial disparities, published in the August issue of the American Journal of Surgery, suggest that injury-prevention programs — like state laws mandating the use of motorcycle helmets — may not be sufficient to protect all riders equally.

"For reasons ...

Withering well can improve fertility

2010-09-24

Contrary to a thousand face cream adverts, the secret of fertility might not be eternal youth. Research by the ecologist Dr. Carlos Herrera, a Professor of Research at the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas in Seville, Spain has shown that the withering action of flowers may have evolved to protect their seeds. His research is published in the October 2010 issue of the Annals of Botany (http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq160).

Prof. Herrera said: "No one has paid much attention to the corollas, collections of petals on a flower, when they shrivel. Their job ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Taking a new look at old digs: Trampling animals may alter Stone Age sitesStudy found water buffalo and goats pushed artifacts deep into mud, potentially altering a site's interpretation by thousands of years