(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR, Mich.—A University of Michigan cell biologist and his colleagues have identified a potential drug that speeds up trash removal from the cell's recycling center, the lysosome.

The finding suggests a new way to treat rare inherited metabolic disorders such as Niemann-Pick disease and mucolipidosis Type IV, as well as more common neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, said Haoxing Xu, who led a U-M team that reported its findings March 13 in the online, multidisciplinary journal Nature Communications.

"The implications are far-reaching," said Xu, an assistant professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology. "We have introduced a novel concept—a potential drug to increase clearance of cellular waste—that could have a big impact on medicine."

Xu cautioned, however, that the studies are in the early, basic-research stage. Any drug that might result from the research is years away.

In cells, as in cities, disposing of garbage and recycling anything that can be reused is an essential service. In both city and cell, health problems can arise when the process breaks down.

Inside the trillions of cells that make up the human body, the job of chopping up and shipping worn-out cellular components falls to the lysosomes. The lysosomes—there are several hundred of them in each cell—use a variety of digestive enzymes to disassemble used-up proteins, fatty materials called lipids, and discarded chunks of cell membrane, among other things.

Once these materials are reduced to basic biological building blocks, the cargo is shipped out of the lysosome to be reassembled elsewhere into new cellular components.

The steady flow of the materials through and out of the lysosome, called vesicular trafficking, is essential for the health of the cell and the entire organism. If trafficking slows or stops, the result is a kind of lysosomal constipation that can cause or contribute to a variety of diseases, including a group of inherited metabolic disorders called lipid storage diseases. Niemann-Pick is one of them.

In previous studies, Xu and his colleagues showed that proper functioning of the lysosome depends, in part, on the timely flow of calcium ions through tiny, pore-like gateways in the lysosome's surface membrane called calcium channels.

If the calcium channels get blocked, trafficking throughout the lysosome is disrupted and loads of cargo accumulate to unhealthy levels, swelling the lysosome to several times its normal size.

Xu and his colleagues previously determined that a protein called TRPML1serves as the calcium channel in lysosomes and that a lipid known as PI(3,5)P2 opens and closes the gates of the channel. Human mutations in the gene responsible for making TRPML1 cause a 50 to 90 percent reduction in calcium channel activity.

In their latest work, aided by a new imaging method used to study calcium-ion release in the lysosome, Xu and his colleagues show that TRPML1-mediated calcium release is dramatically reduced in Niemann-Pick and mucolipidosis Type IV disease cells.

More importantly, they identify a synthetic small molecule, ML-SA1, that mimics the lipid PI(3,5)P2 and can activate the lysosome's calcium channels, opening the gates and restoring the outward flow of calcium ions.

When ML-SA1 was introduced into mouse cells and human Niemann-Pick Type C cells donated by patients, the increased flow through the lysosome's calcium channels was sufficient to speed trafficking and reduce lysosome storage.

Xu and his colleagues believe it might be possible to use ML-SA1 as a drug to activate lysosome calcium channels and restore normal lysosome function in lipid storage diseases like Niemann-Pick. The same approach might also be used to treat Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's, neurodegenerative diseases that involve lysosome trafficking defects.

Such studies might also provide insights into the aging process, which involves the very slow decline in the lysosomes' ability to chop up and recycle worn-out cellular parts.

"The idea is that for lysosome storage diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and aging, they're all caused or worsened by very reduced or slow trafficking in the cellular recycling center," Xu said.

Next step? The researchers hope to administer ML-SA1 to Niemann-Pick and mucolipidosis Type IV mice to determine if the molecule alleviates symptoms.

In Niemann-Pick disease, harmful quantities of lipids accumulate in the spleen, liver, lungs, bone marrow and brain. The disease has four related types. Type A, the most severe, occurs in early infancy and is characterized by an enlarged liver and spleen, swollen lymph nodes and profound brain damage by the age of 6 months. Children with this type rarely live beyond 18 months. There is currently no cure for Niemann-Pick disease.

INFORMATION:

The first author of the Nature Communications paper is Dongbiao Shen, a graduate student research assistant in the U-M Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology.

Other authors, in addition to Xu, are Xiang Wang, Xinran Li, Xiaoli Zhang, Zepeng Yao, Shannon Dibble and Xian-ping Dong of the U-M Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology; Ting Yu and Andrew Lieberman of the U-M Medical School's Department of Pathology; and Hollis Showalter of the Vahlteich Medicinal Chemistry Core in the U-M College of Pharmacy's Department of Medicinal Chemistry.

The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the ML4 Foundation.

Haoxing Xu: www.mcdb.lsa.umich.edu/faculty_haoxingx.html

U-M Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology: www.mcdb.lsa.umich.edu

U-M biologists find potential drug that speeds cellular recycling

2012-03-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

What future Erasmus students are like is being studied

2012-03-14

What is it that turns an ordinary student into an Erasmus student? A team of researchers at the University Teacher Training College in Vitoria-Gasteiz (UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country) has studied the psychological profile of those students who plan to participate in mobility programmes with that of the ones who are not considering doing so, and has detected signs that would point to differences between the two groups. So it is in fact a subject that invites research. Thanks to this preliminary work, an article has been published in the journal Procedia – Social ...

San Antonio Boudoir Photographer Launches Boudoir4theCure, Supporting Efforts to Find a Cure for Breast Cancer

2012-03-14

Studio Boudoir Photography, San Antonio's premier boudoir photography studio, is proud to announce the launch of Boudoir4theCure. The goal of Boudoir4theCure is to raise funds through various events, which will directly benefit the efforts of the Susan G. Komen Foundation to find a cure for breast cancer.

Boudoir has become one of the hottest trends in photography, as more women boldly step in front of the camera to capture an intimate and elegant side of themselves for a significant other. Most women shoot in lingerie, however, a jersey from a favorite sports team, ...

Research shows 50 years of motherhood manuals set standards too high for new moms

2012-03-14

New research at the University of Warwick into 50 years of motherhood manuals has revealed how despite their differences they have always issued advice as orders and set unattainably high standards for new mums and babies.

Angela Davis, from the Department of History at the University of Warwick, carried out 160 interviews with women of all ages and from all backgrounds to explore their experiences of motherhood for her new book, Modern Motherhood: Women and Family in England, 1945-2000.

She spoke to women about the advice given by six childcare 'experts' who had all ...

University of Warwick research suggests suicide rates higher in Protestant areas than Catholic

2012-03-14

Research from the University of Warwick suggests suicide rates are much higher in protestant areas than catholic areas.

Professor Sascha Becker from the University of Warwick's Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Society (CAGE) has published his latest paper Knocking on Heaven's Door? Protestantism and Suicide.

The study investigates whether religion is an influence in the decision to commit suicide, above and beyond other matters that may play a role, such as the weather, literacy, mental health or financial situation.

Professor Becker and his co-author, ...

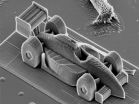

3-D printer with nano precision

2012-03-14

Printing three dimensional objects with incredibly fine details is now possible using "two-photon lithography". With this technology, tiny structures on a nanometer scale can be fabricated. Researchers at the Vienna University of Technology (TU Vienna) have now made a major breakthrough in speeding up this printing technique: The high-precision-3D-printer at TU Vienna is orders of magnitude faster than similar devices (see video). This opens up completely new areas of application, such as in medicine.

Setting a New World Record

The 3D printer uses a liquid resin, which ...

JoVE shows how researchers open the brain to new treatments

2012-03-14

One of the trickiest parts of treating brain conditions is the blood brain barrier, a blockade of cells that prevent both harmful toxins and helpful pharmaceuticals from getting to the body's control center. But, a technique published in JoVE, uses an MRI machine to guide the use of microbubbles and focused ultrasound to help drugs enter the brain, which may open new treatment avenues for devastating conditions like Alzheimer's and brain cancers.

"It's getting close to the point where this could be done safely in humans," said paper-author Meaghan O'Reilly, "there is ...

Scientists tap the cognitive genius of tots to make computers smarter

2012-03-14

People often wonder if computers make children smarter. Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, are asking the reverse question: Can children make computers smarter? And the answer appears to be 'yes.'

UC Berkeley researchers are tapping the cognitive smarts of babies, toddlers and preschoolers to program computers to think more like humans.

If replicated in machines, the computational models based on baby brainpower could give a major boost to artificial intelligence, which historically has had difficulty handling nuances and uncertainty, researchers ...

Reduced baby risk from another cesarean

2012-03-14

A major study led by the University of Adelaide has found that women who have had one prior cesarean can lower the risk of death and serious complications for their next baby - and themselves - by electing to have another cesarean.

The study, known as the Birth After Caesarean (BAC) study, is the first of its kind in the world. It involves more than 2300 women and their babies and 14 Australian maternity hospitals. The results are published this week in the international journal, PLoS Medicine.

The study shows that infants born to women who had a planned elective ...

St. Michael's doctor uses wiki to empower patients and help them to develop asthma action plans

2012-03-14

TORONTO, Ont., March 13, 2012—Imagine that you have asthma, and rather than give you a set of instructions about what to do if you have an attack, your doctor invites you to help write them?

Would that make patients feel more engaged and empowered in managing their health care, and would that ultimately make them happier if not healthier?

These questions are being raised by Dr. Samir Gupta, a respirologist at St. Michael's Hospital.

His research has found that a wiki – a website developed collaboratively by a community of users, allowing any user to add and edit content ...

Get me out of this slump! Visual illusions improve sports performance

2012-03-14

With the NCAA men's college basketball tournament set to begin, college basketball fans around the United States are in the throes of March Madness. Anyone who has seen a game knows that the fans are like extra players on the court, and this is especially true during critical free throws. Fans of the opposing team will wave anything they can, from giant inflatable noodles to big heads, to make it difficult for players to focus on the basket.

But one way a player might be able to improve his chances at making that free throw is by tricking himself into thinking the basket ...