An internationally known expert in immunotherapy research, Weiner was invited, along with Michael T. Lotze, M.D. from the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, by NEJM editors to write an analysis of anticancer immune responses based on a recent report published in the journal Cell (Dec.16, 2011.)

The emerging science described in the cell report reveals how some dying cancer cells may trigger a lasting anti-cancer immune response that can prevent cancer relapses and improve the benefits of treatments. "This is a really exciting development, because we know that manipulating the body's immune system has proven to be the most powerful way to cure advanced cancer that cannot be cured by surgery or radiation treatments," Weiner says.

"We now know that how cancer cells die matters, and so we should strive to manipulate that death in a way that primes the body to destroy any cancer that returns," he says. "This might vastly improve cancer care."

The recent Cell study, conducted primarily by researchers in France, focused on autophagy, which means, literally, "self eating."

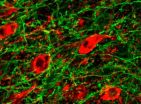

When cells die, the body cleans up the debris by using special cells that ingest and process the cell's component parts so that they can be recycled and used again. During this process, these parts are revealed so that roving protective cells of the immune system can determine if what was inside the cell was potentially harmful. If deemed dangerous, the immune system goes on permanent watch for these molecules so that they can be destroyed.

Cancer cells can die in several ways, Weiner says. One is a natural process called apoptosis, or programmed cell death, which is a way that the body keeps the cells growing within an organ or body in check. "This is a normal process, so the immune system ignores those cells," Weiner says. Many cancer drugs are designed to promote apoptosis.

The other way is autophagy, which can occur when cancer cells are distressed or under attack from toxic agents. Autophagy, which literally means "self-eating", involves the digestion of some parts of a cell to create energy and keep that cell alive. This process triggers the immune system to recognize the cells as a foreign invader that should be destroyed.

What hadn't been known until the Cell study was how the body's immune cells "see" cancer cells as foreign during autophagy – what is it within the cancerous cell that alerts those fighters to be on patrol for development of new cancer cells? "Cancer cells are derived from normal human cells, so something unusual alerts the immune system during autophagy," Weiner says.

In the Cell study, the French researchers discovered that when cancer cells are dying via autophagy, it is the release of energy in the cancer cell, in the form of the chemical ATP, that alerts immune cells to the existence of a big problem. This ATP activates toll-like immune cell receptors, which are a very primitive group of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system by acting as alarms. (It is important to note that the two scientists who discovered the toll-like immune cell receptors shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology.)

The implication for cancer care, then, is to "look at how different drugs kill cancer, and find those that result in autophagy," he says.

Additionally, drugs could be designed that force cancer cells to produce ATP when they are sick and dying, Weiner says. "That way, the immune system is primed to attack cancer that recurs."

In order for this strategy to be effective, researchers will have to develop ways to measure how effectively cancer drugs promote autophagy, he says.

"So instead of looking at how many cancer cells a drug can kill, we should think about developing drugs that help cells die the way we want them to die," Weiner says. Still, there is a lot of work to do, Weiner says. "No tools exist today to measure which chemotherapy agent or combinations act by stimulating the immune system to control cancers."

Progress in this area will require a "change in thinking."

"For many years, it has been thought that chemotherapy damages the immune system, lowering the levels of white blood cells that can fight invaders," he says. "But now researchers are beginning to realize that certain types of chemotherapy and other biologic and targeted treatments may be stimulating a powerful immune response.

"No doubt modern chemotherapeutic and targeted therapy have a powerful impact on the well-being of people with cancer," Weiner says. "But it is also true that we have a long way to go, and this new potential strategy is truly exciting."

###

Weiner serves as an expert consultant on cancer immunotherapy to several pharmaceutical companies, none of whose products are mentioned in this article.

About Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, part of Georgetown University Medical Center and MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, seeks to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer through innovative basic and clinical research, patient care, community education and outreach, and the training of cancer specialists of the future. Georgetown Lombardi is one of only 40 comprehensive cancer centers in the nation, as designated by the National Cancer Institute, and the only one in the Washington, DC, area. For more information, go to http://lombardi.georgetown.edu.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

Georgetown University Medical Center is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC's mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization (BGRO), which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical Translation and Science Award from the National Institutes of Health. In fiscal year 2010-11, GUMC accounted for 85 percent of the university's sponsored research funding.

END