(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—What happens to a stem cell at the molecular level that causes it to become one type of cell rather than another? At what point is it committed to that cell fate, and how does it become committed? The answers to these questions have been largely unknown. But now, in studies that mark a major step forward in our understanding of stem cells' fates, a team of researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) has traced the stepwise developmental process that ensures certain stem cells will become T cells—cells of the immune system that help destroy invading pathogens.

"This is the first time that a natural developmental process has been dissected in such detail, going from step to step to step, looking at activities of all the genes in the genome," says Ellen Rothenberg, the principal investigator on the study and the Albert Billings Ruddock Professor of Biology at Caltech. "It means that in genetic terms, there is virtually nothing left hidden in this system."

The study was led by Jingli A. Zhang, a graduate student in Rothenberg's lab, who is now a postdoctoral scholar at Caltech. The group's findings appear in the April 13 issue of the journal Cell.

The researchers studied multipotent hematopoietic precursor cells—stem-cell-like cells that express a wide variety of genes and have the capability to differentiate into a number of different blood-cell types, including those of the immune system. Taking into consideration the entire mouse genome, the researchers pinpointed all the genes that play a role in transforming such precursor cells into committed T cells and identified when in the developmental process they each turn on. At the same time, the researchers tracked genes that could guide the precursor cells to various alternative pathways. The results showed not only when but also how the T-cell-development process turned off the genes promoting alternative fates.

"We were able to ask, 'Do T-cell genes turn on before the genes that promote some specific alternative to T cells turn off, or does it go in the other order? Which genes turn on first? Which genes turn off first?'" Rothenberg explains. "In most genome-wide studies, you rarely have the ability to see what comes first, second, third, and so on, in a developmental progression. And establishing those before-after relationships is absolutely critical if you want to understand such a complicated process."

The researchers studied five stages in the cascade of molecular events that yields a T cell—two before commitment, a commitment stage, and then two following commitment. They identified the genes that are expressed throughout those stages, including many that code for regulatory proteins, called transcription factors, which turn particular genes on or off. They found that a major regulatory shift occurs between the second and third stages, when T-cell commitment sets in. At that point, a large number of the transcription factors that activate genes associated with uncommitted stem cells turn off, while others that activate genes needed for future steps in T-cell development turn on.

The researchers looked not only at which genes are expressed during the various stages but also at what makes it possible for those genes to be expressed at that particular time. One critical component of regulation is the expression of transcription-factor genes themselves. Beyond that, the researchers were interested in identifying control sequences—the parts of genes that serve as docking sites for transcription factors. These sequences are often very difficult to identify in mice and humans using classical molecular-biology techniques; scientists have spent as many as 10 years trying to create a comprehensive map of the control sequences for a single gene.

To create a map of likely control sequences, Zhang studied epigenetic markers. These are chemical modifications, such as those that change the way the DNA is bundled. They become associated with particular regions of DNA as a result of the action of transcription factors and can thereby affect how easy or hard it is for a neighboring gene to be turned on or off. By identifying DNA regions where epigenetic markers are added or removed, Rothenberg's group has paved the way for researchers to identify control sequences for many of the genes that turn on or off during T-cell development.

In some ways, Rothenberg says, her team is taking a backward approach to the problem of locating these control sequences. "What we're saying is, if we can tell that a gene is turned on at a certain point in terms of producing RNA, then we should also be able to look at the DNA sequences right around it and ask, 'Is there any stretch of DNA sequence that adds or loses epigenetic markers at the same time?'" Rothenberg says. "If we find it, that can be a really hot candidate for the control sequences that were used to turn that gene on."

Two methodologies have made it possible to complete this work. First, ultra-high-throughput DNA sequencing was used to identify when major changes in gene expression occur along the developmental pathway. This technique amplifies DNA sequences taken throughout millions of cell samples, puts all of the bits in order, compares them to the known genome sequence (for mice, in this case), and identifies which of the various genes are enriched, or found in greater numbers. Those that are enriched are the ones most likely to be expressed. The team also used a modified version of this sequencing technique to identify the parts of the genome that are associated with particular epigenetic markers. Coauthor Barbara Wold, Caltech's Bren Professor of Molecular Biology, is an expert in these so-called "next-generation" deep-sequencing technologies and provided critical inspiration for the study.

A second important methodology involved an in vitro tissue-culture system developed in the lab of Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker of the University of Toronto, which enabled the Caltech researchers to mass-produce synchronized early T-cell precursors and to see the effect of altered conditions on individual cells in terms of producing T cells or other cells.

INFORMATION:

Zhang is lead author of the paper in Cell, titled "Dynamic transformations of genome-wide epigenetic marking and transcriptional control establish T cell identity." In addition to Zhang, Rothenberg, and Wold, Brian Williams, a senior scientific researcher at Caltech, was also a coauthor. Another coauthor, developmental biologist Ali Mortazavi, was part of Wold's lab and was also associated with the lab of Paul Sternberg when the work was completed; he is now an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine.

The work was supported by the Beckman Institute, the Millard and Muriel Jacobs Genetics and Genomics Laboratory, the L.A. Garfinkle Memorial Laboratory Fund, the Al Sherman Foundation, the Bren Professorship, the A.B. Ruddock Professorship, and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Written by Kimm Fesenmaier

Determining a stem cell's fate

Caltech biologists scour mouse genome for genes and markers that lead to T cells

2012-04-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New research puts focus on earthquake, tsunami hazard for southern California

2012-04-13

San Francisco, April 12, 2012 -- Scientists will convene in San Diego to present the latest seismological research at the annual conference of the Seismological Society of America (SSA), April 17-19.

This year's meeting is expected to draw a record number of registrants, with more than 630 scientists in attendance, and will feature 292 oral presentations and 239 poster presentations.

"For over 100 years the Annual Meeting of SSA has been the forum of excellence for presenting and discussing exciting new developments in seismology research and operations in the U.S. ...

Traffic harms Asturian amphibians

2012-04-13

The roads are the main cause of fragmenting the habitats of many species, especially amphibians, as they cause them to be run over and a loss of genetic diversity. Furthermore, traffic harms two abundant species that represent the amphibious Asturian fauna and have been declared vulnerable in Spain: the midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) and the palmate newt (Lissotriton helveticus).

"But midwife toad and palmate newt populations have very different sensitivities to the effects of roads" Claudia García-González, researcher at the University of Oviedo, told SINC. "These ...

Nutrient and toxin all at once: How plants absorb the perfect quantity of minerals

2012-04-13

In order to survive, plants should take up neither too many nor too few minerals from the soil. New insights into how they operate this critical balance have now been published by biologists at the Ruhr-Universität in a series of three papers in the journal The Plant Cell. The researchers discovered novel functions of the metal-binding molecule nicotianamine. "The results are important for sustainable agriculture and also for people – to prevent health problems caused by deficiencies of vital nutrients in our diet" says Prof. Dr. Ute Krämer of the RUB Department of Plant ...

Herschel sees dusty disc of crushed comets

2012-04-13

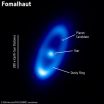

Astronomers using ESA's Herschel Space Observatory have studied a ring of dust around the nearby star Fomalhaut and have deduced that it is created by the collision of thousands of comets every day.

Fomalhaut, a star twice as massive as our Sun and around 25 light years away, has been of keen interest to astronomers for many years. With an age of only a few hundred million years it is a fairly young star, and in the 1980s was shown to be surrounded by relatively large amounts of dust by the IRAS infrared satellite. Now Herschel, with its unprecedented resolution, has ...

Study resolves debate on human cell shut-down process

2012-04-13

Researchers at the University of Liverpool have resolved the debate over the mechanisms involved in the shut-down process during cell division in the body.

Research findings, published in the journal PNAS, may contribute to future studies on how scientists could manipulate this shut-down process to ensure that viruses and other pathogens do not enter the cells of the body and cause harm.

Previous research has shown that when cells divide, they cannot perform any other task apart from this one. They cannot, for example, take in food and fluids at the same time as ...

Multitasking – not so bad for you after all?

2012-04-13

Our obsession with multiple forms of media is not necessarily all bad news, according to a new study by Kelvin Lui and Alan Wong from The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Their work shows that those who frequently use different types of media at the same time appear to be better at integrating information from multiple senses - vision and hearing in this instance - when asked to perform a specific task. This may be due to their experience of spreading their attention to different sources of information while media multitasking. Their study is published online in Springer's ...

New advances in the understanding of cancer progression

2012-04-13

Researchers at the Hospital de Mar Research Institute (IMIM) have discovered that the protein LOXL2 has a function within the cell nucleus thus far unknown. They have also described a new chemical reaction of this protein on histone H3 that would be involved in gene silencing, one of which would be involved in the progression of breast, larynx, lung and skin tumours.

Led by Dr Sandra Peiró and published in Molecular Cell journal, the study is a significant advance in describing the evolution of tumours and opens the door to researching new treatments that block their ...

Genetic adaptation of fat metabolism key to development of human brain

2012-04-13

About 300 000 years ago humans adapted genetically to be able to produce larger amounts of Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids. This adaptation may have been crucial to the development of the unique brain capacity in modern humans. In today's life situation, this genetic adaptation contributes instead to a higher risk of developing disorders like cardiovascular disease.

The human nervous system and brain contain large amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and these are essential for the development and function of the brain. These Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids occur ...

Stem cells 'by default'

2012-04-13

Casanova's notion is that stem cells emerge not because of the presence of factors that confer capacity to the stem cell but because of factors that repress the cellular signals for differentiation and specialization. Casanova believes that somehow all non-differentiated cells intrinsically carry the qualities of the stem cell by default and that there are factors at work that remove these capacities. Said another way: a stem cell is a stem cell because it has evaded differentiation. According to Casanova, if the idea of "a stem cell by default" is considered, research ...

Gulf Coast residents say BP Oil Spill changed their environmental views, UNH research finds

2012-04-13

DURHAM, N.H. -- University of New Hampshire researchers have found that residents of Louisiana and Florida most acutely and directly affected by the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster -- the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history -- said they have changed their views on other environmental issues as a result of the spill.

"If disasters teach any lessons, then experience with the Gulf oil spill might be expected to alter opinions about the need for environmental protection. About one-fourth of our respondents said that as a result of the spill, their views on other environmental ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

People’s gut bacteria worse in areas with higher social deprivation

Unique analysis shows air-con heat relief significantly worsens climate change

Keto diet may restore exercise benefits in people with high blood sugar

Manchester researchers challenge misleading language around plastic waste solutions

Vessel traffic alters behavior, stress and population trends of marine megafauna

Your car’s tire sensors could be used to track you

Research confirms that ocean warming causes an annual decline in fish biomass of up to 19.8%

Local water supply crucial to success of hydrogen initiative in Europe

New blood test score detects hidden alcohol-related liver disease

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

[Press-News.org] Determining a stem cell's fateCaltech biologists scour mouse genome for genes and markers that lead to T cells