(Press-News.org) SALT LAKE CITY, June 6, 2012 – Talk about throwing yourself into a relationship too soon.

A University of Utah study found that when a virgin male moth gets a whiff of female sex attractant, he's quicker to start shivering to warm up his flight muscles, and then takes off prematurely when he's still too cool for powerful flight. So his headlong rush to reach the female first may cost him the race.

The study illustrates the tradeoff between being quick to start flying after a female versus adequately warming up the flight muscles before starting the chase. Until the next study, it remains a mystery which moths actually reach the females: the too-cool, quick-takeoff males or the males who wait until they're hot enough to take a shot. The latter may end up flying faster and more efficiently and win the race, despite a slow takeoff.

"What happens before flight has not been well studied," says José Crespo, a University of Utah doctoral student in biology and first author of the new study, published online June 7 in the Journal of Experimental Biology. "To me, the story is you have a behavior – pre-flight warmup – that is switched on by smell."

Senior author Neil Vickers, professor and chairman of biology at the University of Utah, says: "In many insects, moths in particular, all of their adult lives are affected by odor – all the activities they engage in that you and I see at night at the porch light are things typically affected by odor."

Moths forage for nectars using flower odors. Males follow female sex attractants or pheromones to find the females. Then they have what Vickers calls "an odor dialogue" and mate. The females use odor to lay their eggs on the right plants.

"Finding out how odors switch on behavior is critical to the whole picture," Vickers says. "Furthermore, because insects have this amazing ability to fly, which not many animals have, finding out how flight is turned on by odor is an issue relevant to many insects. … There is a whole constellation of behaviors driven by odor, and this is true of all manner of insects" and even other animals and people.

Vickers and Crespo conducted the study with University of Utah biology Professor Franz Goller. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

Watching Chilled Moths Heat Up

The study involved a moth named Helicoverpa zea, commonly known as the corn ear worm. It belongs to the largest family of moths and butterflies – noctuids – which have more than 35,000 species worldwide, including the medium-sized moths many of us see in or near our homes.

"It's a significant agricultural pest which attacks many different crops – corn, soy, tomato, strawberries," Vickers says. Researchers use them because they are good models to show how odors are processed in the brain.

Virgin males were used in the study because it is standard protocol to use animals that haven't previously mated or been exposed to pheromones.

To start the experiments, all the moths were chilled down to 46 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit, cool enough so they stay inactive, and so handling them before the experiments doesn't prompt them to start warming up immediately.

The first experiments were conducted using a small, open roofed, cardboard wind tunnel about 11 inches long, 5.5 inches wide and 5.5 inches tall. A 1.2-inch tall, 1.2-inch diameter cylindrical wire cage, with no top, was placed upright inside one end of the wind tunnel, with an inactive moth at the bottom.

A fan blew a gentle, 1 mph breeze toward the moth, and one of six odors was released near the upwind end of the tube. One was the moth's normal pheromone blend, one was the blend's primary component, and the other four were odors (or in one case, no odor) that scientists believed wouldn't attract the moths (and didn't).

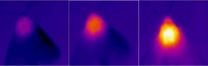

An infrared video camera – which measures temperatures – recorded the moths as they began their shivering warm-up and finally took off. The moths are seen in infrared turning from cooler purple-blue to warmer orange and even warmer red and yellow.

By analyzing the video after each of dozens of experiments, Crespo measured how long it took inactive moths to start shivering after smelling the odor, and how long they spent shivering until takeoff. The infrared video, one frame before takeoff, showed the temperature of the moth's thorax at takeoff (the wings and all related muscles are in the insect's thorax, the body section between the head and abdomen). Crespo also calculated the rate at which the moths warmed up.

Moths that did not smell pheromone flew in random directions when they finally warmed up. Moths that smelled the pheromone blend (and often the primary component alone) started shivering faster, took off sooner (less time shivering), did so at a lower temperature than other moths, and flew toward the odor.

Quicker Takeoff, Less Powerful Flight

Until now, researchers thought the moths simply warmed up as fast as they can. "These guys don't all heat up at the same rate," Vickers says. "The guys exposed to the pheromone odor, go 'Wow!' and they warm up faster and take off more quickly. And that compromises the flight power they can produce."

Crespo conducted a second set of experiments that showed cooler temperatures mean less vertical flight power or force.

In these experiments, wax was used to gently attach (not stick) an entomological pin to a moth's thorax. The other end of the pin was attached to a force sensor, which in turn was wired to various electronics to read the results. A small Styrofoam ball was placed under the moth, which reflexively grabbed onto it with its legs. When Crespo gently pulled away the ball, the moth reflexively tried to fly upward, and the force of that effort was recorded. White and black lights – to which moths are attracted – were above the apparatus to induce the moths to fly with maximum force.

The test was repeated in small temperature increments, showing how warm a moth thorax must be for maximum flight power – about 90 degrees Fahrenheit – and that those in the study took off too cool at about 82 degrees Fahrenheit.

Crespo says moths "are well-known for 'scramble competition.' When the female is advertising the pheromone in a field, that pheromone is probably going to be detected by several males, and they're going to try to compete and get to the female first. You can see how it might be advantageous to take off sooner and try to get to the female first."

"However," he adds, "if you take off with a lower temperature, we show you have less maximum power in flight, so we think there is a compromise between heating up faster to a lower temperature to arrive at that female first, or waiting a little longer to heat up to a higher temperature and make sure you're going to make it to the female."

"This is about a decision to get up and go: 'This is the right smell. Let's do it,'" Vickers says. "There are neurons that detect the odor, and they feed that information into the brain, and the brain says, 'This is the right odor, this is a female,' and then processes occur that we don't know much about. But the brain sends instructions to the flight muscles to start warming up. The animal responds to this odor by warming itself at a faster rate than if it's exposed to a non-female odor. At some level, we've moved a little step closer to understanding that black box that's evaluating these inputs and internal conditions and deciding to move."

Vickers adds: "Insect flight muscles are among the most metabolically costly in the animal kingdom. In order to fly, you have to use a lot of oxygen and generate the power. The decision to take flight after a female odor is not one that would be taken lightly by the moth because it's expensive."

"It's costly to fly, to jump into a relationship," he says.

INFORMATION:

Video and infrared video of a moth warming up may be viewed at:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1pXzlyIk8s

University of Utah Communications

201 Presidents Circle, Room 308

Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-9017

(801) 581-6773 fax: (801) 585-3350

www.unews.utah.edu

Virgin male moths think they're hot when they're not

Female sex odor makes cool males take flight too soon

2012-06-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Vampire jumping spiders identify victims by their antennae

2012-06-08

Evarcha culicivora jumping spiders, also known as vampire spiders, are picky eaters by any standards. Explaining that the arachnid's environment is swamped with insects, Ximena Nelson from the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, says, 'You can see from the diet when you find them in the field that there is a high number of mosquitoes in what they eat'. And when Robert Jackson investigated their diet further, he found that the spiders were even more selective. The delicacy that E. culicivora prize above all others is female blood-fed Anopheles mosquitoes, which puzzled ...

Pre-existing mutations can lead to drug resistance in HIV virus

2012-06-08

In a critical step that may lead to more effective HIV treatments, Harvard scientists have found pre-existing mutations in a small number of HIV patients. These mutations can cause the virus to develop resistance to the drugs used to slow its progression.

The finding is particularly important because, while researchers have long known HIV can develop resistance to some drugs, it was not understood whether the virus relied on pre-existing mutations to develop resistance, or if it waits for those mutations to occur. By shedding new light on how resistance evolves, the study, ...

Study sheds new light on role of genetic mutations in colon cancer development

2012-06-08

SEATTLE – In exploring the genetics of mitochondria – the powerhouse of the cell – researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center have stumbled upon a finding that challenges previously held beliefs about the role of mutations in cancer development.

For the first time, researchers have found that the number of new mutations are significantly lower in cancers than in normal cells.

"This is completely opposite of what we see in nuclear DNA, which has an increased overall mutation burden in cancer," said cancer geneticist Jason Bielas, Ph.D., whose findings are published ...

Gladstone scientists reprogram skin cells into brain cells

2012-06-08

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—June 7, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have for the first time transformed skin cells—with a single genetic factor—into cells that develop on their own into an interconnected, functional network of brain cells. The research offers new hope in the fight against many neurological conditions because scientists expect that such a transformation—or reprogramming—of cells may lead to better models for testing drugs for devastating neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease.

This research comes at a time of renewed focus on Alzheimer's ...

All the colors of a high-energy rainbow, in a tightly focused beam

2012-06-08

For the first time, researchers have produced a coherent, laser-like, directed beam of light that simultaneously streams ultraviolet light, X-rays, and all wavelengths in between.

One of the few light sources to successfully produce a coherent beam that includes X-rays, this new technology is the first to do so using a setup that fits on a laboratory table.

An international team of researchers, led by engineers from the NSF Engineering Research Center (ERC) for EUV Science and Technology, reports their findings in the June 8, 2012, issue of Science.

By focusing intense ...

Bright X-ray flashes created in laser lab

2012-06-08

A breakthrough in laser science was achieved in Vienna: In the labs of the Photonics Institute at the Vienna University of Technology, a new method of producing bright laser pulses at x-ray energies was developed. The radiation covers a broad energy spectrum and can therefore be used for a wide range of applications, from materials science to medicine. Up until now, similar kinds of radiation could only be produced in particle accelerators (synchrotrons), but now a laser laboratory can also achieve this. The new laser technology was presented in the current issue of the ...

Newly identified protein function protects cells during injury

2012-06-08

CINCINNATI – Scientists have discovered a new function for a protein that protects cells during injury and could eventually translate into treatment for conditions ranging from cardiovascular disease to Alzheimer's.

Researchers report online June 7 in the journal Cell that a type of protein called thrombospondin activates a protective pathway that prevents heart cell damage in mice undergoing simulated extreme hypertension, cardiac pressure overload and heart attack.

"Our results suggest that medically this protein could be targeted as a way to help people with many ...

Report addresses challenges in implementing new diagnostic tests where they are needed most

2012-06-08

Easy-to-use, inexpensive tests to diagnose infectious diseases are urgently needed in resource-limited countries. A new report based on an American Academy of Microbiology colloquium, "Bringing the Lab to the Patient: Developing Point-of-Care Diagnostics for Resource Limited Settings," describes the challenges inherent in bringing new medical devices and technologies to the areas of the world where they are needed most. Point-of-care diagnostics (POCTs) bypass the need for sophisticated laboratory systems by leveraging new technologies to diagnose infectious diseases and ...

11 integrated health systems form largest private-sector diabetes registry in US

2012-06-08

(PORTLAND, Ore.) —June 07, 2012—Eleven integrated health systems, with more than 16 million members, have combined de-identified data from their electronic health records to form the largest, most comprehensive private-sector diabetes registry in the nation.

According to a new study published today in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Preventing Chronic Disease, the SUPREME-DM DataLink provides a unique and powerful resource to conduct population-based diabetes research and clinical trials.

"The DataLink will allow us to compare more prevention and ...

U Alberta finds weakness in armor of killer hospital bacteria

2012-06-08

There's new hope for development of an antibiotic that can put down a lethal bacteria or superbug linked to the deaths of hundreds of hospital patients around the world.

Researchers from the University of Alberta-based Alberta Glycomics Centre found a chink in the molecular armour of the pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. The bacteria first appeared in the 1970's and in the last decade it developed a resistance to most antibiotics.

U of A microbiologist Mario Feldman identified a mechanism that allows Acinetobacter baumannii to cover its surface with molecules knows ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

Flagging claims about cancer treatment on social media as potentially false might help reduce spreading of misinformation, per online experiment with 1,051 US adults

Yawns in healthy fetuses might indicate mild distress

Conservation agriculture, including no-dig, crop-rotation and mulching methods, reduces water runoff and soil loss and boosts crop yield by as much as 122%, in Ethiopian trial

Tropical flowers are blooming weeks later than they used to through climate change

Risk of whale entanglement in fishing gear tied to size of cool-water habitat

Climate change could fragment habitat for monarch butterflies, disrupting mass migration

Neurosurgeons are really good at removing brain tumors, and they’re about to get even better

Almost 1-in-3 American adolescents has diabetes or prediabetes, with waist-to-height ratio the strongest independent predictor of prediabetes/diabetes, reveals survey of 1,998 adolescents (10-19 years

Researchers sharpen understanding of how the body responds to energy demands from exercise

New “lock-and-key” chemistry

Benzodiazepine use declines across the U.S., led by reductions in older adults

How recycled sewage could make the moon or Mars suitable for growing crops

Don’t Panic: ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’ has begun

A robust new telecom qubit in silicon

Vertebrate paleontology has a numbers problem. Computer vision can help

[Press-News.org] Virgin male moths think they're hot when they're notFemale sex odor makes cool males take flight too soon