(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- In the days following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, methane-eating bacteria bloomed in the Gulf of Mexico, feasting on the methane that gushed, along with oil, from the damaged well. The sudden influx of microbes was a scientific curiosity: Prior to the oil spill, scientists had observed relatively few signs of methane-eating microbes in the area.

Now researchers at MIT have discovered a bacterial gene that may explain this sudden influx of methane-eating bacteria. This gene enables bacteria to survive in extreme, oxygen-depleted environments, lying dormant until food — such as methane from an oil spill, and the oxygen needed to metabolize it — become available. The gene codes for a protein, named HpnR, that is responsible for producing bacterial lipids known as 3-methylhopanoids. The researchers say producing these lipids may better prepare nutrient-starved microbes to make a sudden appearance in nature when conditions are favorable, such as after the Deepwater Horizon accident.

The lipid produced by the HpnR protein may also be used as a biomarker, or a signature in rock layers, to identify dramatic changes in oxygen levels over the course of geologic history.

"The thing that interests us is that this could be a window into the geologic past," says MIT postdoc Paula Welander, who led the research. "In the geologic record, many millions of years ago, we see a number of mass extinction events where there is also evidence of oxygen depletion in the ocean. It's at these key events, and immediately afterward, where we also see increases in all these biomarkers as well as indicators of climate disturbance. It seems to be part of a syndrome of warming, ocean deoxygenation and biotic extinction. The ultimate causes are unknown."

Welander and Roger Summons, a professor of Earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences, have published their results this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A sign in the rocks

Earth's rocky layers hold remnants of life's evolution, from the very ancient traces of single-celled organisms to the recent fossils of vertebrates. One of the key biomarkers geologists have used to identify the earliest forms of life is a class of lipids called hopanoids, whose sturdy molecular structure has preserved them in sediment for billions of years. Hopanoids have also been identified in modern bacteria, and geologists studying the lipids in ancient rocks have used them as signs of the presence of similar bacteria billions of years ago.

But Welander says hopanoids may be used to identify more than early life forms: The molecular fossils may be biomarkers for environmental phenomena — such as, for instance, periods of very low oxygen.

To test her theory, Welander examined a modern strain of bacteria called Methylococcus capsulatus, a widely studied organism first isolated from an ancient Roman bathhouse in Bath, England. The organism, which also lives in oxygen-poor environments such as deep-sea vents and mud volcanoes, has been of interest to scientists for its ability to efficiently consume large quantities of methane — which could make it helpful in bioremediation and biofuel development.

For Welander and Summons, M. capsulatus is especially interesting for its structure: The organism contains a type of hopanoid with a five-ring molecular structure that contains a C-3 methylation. Geologists have found that such methylations in the ring structure are particularly well-preserved in ancient rocks, even when the rest of the organism has since disappeared.

Welander pored over the bacteria's genome and identified hpnR, the gene that codes for the protein HpnR, which is specifically associated with C-3 methylation. She devised a method to delete the gene, creating a mutant strain. Welander and Summons then grew cultures of this mutant strain, as well as cultures of wild, unaltered bacteria. The team exposed both strains to low levels of oxygen and high levels of methane over a two-week period to simulate an oxygen-poor environment.

During the first week, there was little difference between the two groups, both of which consumed methane and grew at about the same rate. However, on day 14, the researchers observed the wild strain begin to outgrow the mutant bacteria. When Welander added the hpnR gene back into the mutant bacteria, she found they eventually bounced back to levels that matched the wild strain.

Just getting by to survive

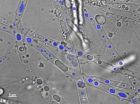

What might explain the dramatic contrast in survival rates? To answer this, the team used electron microscopy to examine the cellular structures in both mutant and wild bacteria. They discovered a stark difference: While the wild type was filled with normal membranes and vacuoles, the mutant strain had none.

The missing membranes, Welander says, are a clue to the lipid's function. She and Summons posit that the hpnR gene may preserve bacteria's cell membranes, which may reinforce the microbe in times of depleted nutrients.

"You have these communities kind of just getting by, surviving on what they can," Welander says. "Then when they get a blast of oxygen or methane, they can pick up very quickly. They're really poised to take advantage of something like this."

The results, Welander says, are especially exciting from a geological perspective. If 3-methylhopanoids do indeed allow bacteria to survive in times of low oxygen, then a spike of the related lipid in the rock record could indicate a dramatic decrease in oxygen in Earth's history, enabling geologists to better understand periods of mass extinctions or large ocean die-offs.

"The original goal was [to] make this a better biomarker for geologists," Welander says. "It's very meticulous [work], but in the end we also want to make a broader impact, such as learning how microorganisms deal with hydrocarbons in the environment."

###This research was supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Newfound gene may help bacteria survive in extreme environments

Resulting microbial lipids may also signify oxygen dips in Earth's history

2012-07-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Identifying the arrogant boss

2012-07-26

VIDEO:

Are all bosses arrogant?

Click here for more information.

Akron, Ohio, July 25, 2012 – Arrogant bosses can drain the bottom line because they are typically poor performers who cover up their insecurities by disparaging subordinates, leading to organizational dysfunction and employee turnover.

A new measure of arrogance, developed by researchers at The University of Akron and Michigan State University, can help organizations identify arrogant managers before they have ...

Protected areas face threats in sustaining biodiversity, Penn's Daniel Janzen and colleagues report

2012-07-26

PHILADELPHIA — Establishing protection over a swath of land seems like a good way to conserve its species and its ecosystems. But in a new study, University of Pennsylvania biologist Daniel Janzen joins more than 200 colleagues to report that protected areas are still vulnerable to damaging encroachment, and many are suffering from biodiversity loss.

"If you put a boundary around a piece of land and install some bored park guards and that's all you do, the park will eventually die," said Janzen, DiMaura Professor of Conservation Biology in Penn's Department of Biology. ...

Citizen science helps unlock European genetic heritage

2012-07-26

A University of Sheffield academic is helping a team of citizen scientists to carry out crucial research into European genetic heritage.

Citizen Scientists are not required to have a scientific background or training, but instead they possess a passion for the subject and are increasingly being empowered by the scientific community to get involved in research.

Dr Andy Grierson, from the University of Sheffield's Institute for Translational Neuroscience (SITraN), has helped a team of citizen scientists from Europe and North America to identify vital new clues to tell ...

Medical follow-up in celiac disease is less than optimal

2012-07-26

Follow-up exams for patients with celiac disease are often inadequate and highly variable, according to a new study in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).

"In the group of celiac disease patients that we observed, we found that very few of them had medical follow-up that would be in keeping with even the most lax interpretation of current guidelines," said Joseph A. Murray, MD, AGAF, of Mayo Clinic and lead author of this study. "Doctors and patients need to be aware of ...

Global expansion all about give and take, study finds

2012-07-26

EAST LANSING, Mich. — The key to successful global business expansion is spreading operations across multiple countries, rather than trying to dominate a region or market, according to a new study led by Michigan State University researchers.

In addition, since global expansion is costly for service industries, manufacturing industries will profit most, said Tomas Hult, director of MSU's International Business Center.

Led by Hult and Ahmet Kirca, associate professor of marketing, the study is the largest ever conducted to examine the effect of multinationality on firm ...

Spatial skills may be improved through training, new review finds

2012-07-26

Spatial skills--those involved with reading maps and assembling furniture--can be improved if you work at it, that's according to a new look at the studies on this topic by researchers at Northwestern University and Temple.

The research published this month in Psychological Bulletin, the journal of the American Psychological Association, is the first comprehensive analysis of credible studies on such interventions.

Improving spatial skills is important because children who do well at spatial tasks such as putting together puzzles are likely to achieve highly in science, ...

Contaminant transport in the fungal pipeline

2012-07-26

This press release is available in German.

Leipzig. Fungi are found throughout the soil with giant braiding of fine threads. However, these networks have surprising functions. Only a few years ago researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) discovered that bacteria travel over the fungal threads through the labyrinth of soil pores, much the same as on a highway. Now, together with British colleagues from the University of Lancaster, the UFZ researchers have come upon another phenomenon. Accordingly, the fungal networks also transports contaminants ...

Miriam researchers urge physicians to ask younger men about erectile dysfunction symptoms

2012-07-26

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – Although erectile dysfunction (ED) has been shown to be an early warning sign for heart disease, some physicians – and patients – still think of it as just as a natural part of "old age." But now an international team of researchers, led by physicians at The Miriam Hospital, say it's time to expand ED symptom screening to include younger and middle-aged men.

In an article appearing in the July issue of the American Heart Journal, they encourage physicians to inquire about ED symptoms in men over the age of 30 who have cardiovascular risk factors, such ...

In muscular dystrophy, what matters to patients and doctors can differ

2012-07-26

Complex, multi-system diseases like myotonic dystrophy – the most common adult form of muscular dystrophy – require physicians and patients to identify which symptoms impact quality of life and, consequently, what treatments should take priority. However, a new study out this month in the journal Neurology reveals that there is often a disconnect between the two groups over which symptoms are more important, a phenomenon that not only impacts care but also the direction of research into new therapies.

"In order to design better therapies we must first develop a clear ...

New gene therapy strategy boosts levels of deficient protein in Friedreich's ataxia

2012-07-26

New Rochelle, NY, July 25, 2012—A novel approach to gene therapy that instructs a person's own cells to produce more of a natural disease-fighting protein could offer a solution to treating many genetic disorders. The method was used to achieve a 2- to 3-fold increase in production of a protein deficient in patients with Friedreich's ataxia, as described in an article published Instant Online in Human Gene Therapy, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. (http://www.liebertpub.com) The article is available free online at the Human Gene Therapy website (http://www.liebertpub.com/hum).

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

People’s gut bacteria worse in areas with higher social deprivation

Unique analysis shows air-con heat relief significantly worsens climate change

Keto diet may restore exercise benefits in people with high blood sugar

Manchester researchers challenge misleading language around plastic waste solutions

Vessel traffic alters behavior, stress and population trends of marine megafauna

Your car’s tire sensors could be used to track you

Research confirms that ocean warming causes an annual decline in fish biomass of up to 19.8%

Local water supply crucial to success of hydrogen initiative in Europe

New blood test score detects hidden alcohol-related liver disease

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

[Press-News.org] Newfound gene may help bacteria survive in extreme environmentsResulting microbial lipids may also signify oxygen dips in Earth's history