(Press-News.org) In a quest to make safer and more effective vaccines, scientists at the Biodesign InstituteÒ at Arizona State University have turned to a promising field called DNA nanotechnology to make an entirely new class of synthetic vaccines.

In a study published in the journal Nano Letters, Biodesign immunologist Yung Chang joined forces with her colleagues, including DNA nanotechnology innovator Hao Yan, to develop the first vaccine complex that could be delivered safely and effectively by piggybacking onto self-assembled, three-dimensional DNA nanostructures.

"When Hao treated DNA not as a genetic material, but as a scaffolding material, that made me think of possible applications in immunology," said Chang, an associate professor in the School of Life Sciences and a researcher in the Biodesign Institute's Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology. "This provided a great opportunity to try to use these DNA scaffolds to make a synthetic vaccine."

"The major concern was: Is it safe? We wanted to mimic the assembly of molecules that can trigger a safe and powerful immune response in the body. As Hao's team has developed a variety of interesting DNA nanostructures during the past few years, we have been collaborating more and more with a goal to further explore some promising human health applications of this technology."

The core multidisciplinary research team members also included: ASU chemistry and biochemistry graduate student and paper first author Xiaowei Liu, visiting professor Yang Xu, chemistry and biochemistry assistant professor Yan Liu, School of Life Sciences undergraduate Craig Clifford and Tao Yu, visiting graduate student from Sichuan University.

Chang points out that vaccines have led to the some of the most effective public health triumphs in all of medicine. The state-of-the-art in vaccine development relies on genetic engineering to assemble immune system stimulating proteins into virus-like particles (VLPs) that mimic the structure of natural viruses---minus the harmful genetic components that cause disease.

DNA nanotechnology, where the molecule of life can be assembled into 2-D and 3-D shapes, has an advantage of being a programmable system that can precisely organize molecules to mimic the actions of natural molecules in the body.

"We wanted to test several different sizes and shapes of DNA nanostructures and attach molecules to them to see if they could trigger an immune response," said Yan, the Milton D. Glick Distinguished Chair in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and researcher in Biodesign's Center for Single Molecule Biophysics. With their biomimicry approach, the vaccine complexes they tested closely resembled natural viral particles in size and shape.

As proof of concept, they tethered onto separate pyramid-shaped and branched DNA structures a model immune stimulating protein called streptavidin (STV) and immune response boosting compound called an adjuvant (CpG oligo-deoxynucletides) to make their synthetic vaccine complexes.

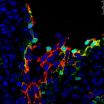

First, the group had to prove that the target cells could gobble the nanostructures up. By attaching a light-emitting tracer molecule to the nanostructures, they found the nanostructures residing comfortably within the appropriate compartment of the cells and stable for several hours----long enough to set in motion an immune cascade.

Next, in a mouse challenge, they targeted the delivery of their vaccine cargo to cells that are first responders in initiating an effective immune response, coordinating interaction of important components, such as: antigen presenting cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells and B cells. After the cargo is internalized in the cell, they are processed and "displayed" on the cell surface to T cells, white blood cells that play a central role in triggering a protective immune response. The T cells, in turn, assist B cells with producing antibodies against a target antigen.

To properly test all variables, they injected: 1) the full vaccine complex 2) STV (antigen) alone 3) the CpG (adjuvant) mixed with STV.

Over the course of 70 days, the group found that mice immunized with the full vaccine complex developed a more robust immune response up to 9-fold higher than the CpG mixed with STV. The pyramid (tetrahedral) shaped structure generated the greatest immune response. Not only was immune response to the vaccine complex specific and effective, but also safe, as the research team showed, using two independent methods, that no immune response triggered from introducing the DNA platform alone.

"We were very pleased," said Chang. "It was so nice to see the results as we predicted. Many times in biology we don't see that."

With the ability to target specific immune cells to generate a response, the team is excited about the prospects of this new platform. They envision applications where they could develop vaccines that require multiple components, or customize their targets to tailor the immune response.

Furthermore, there is the potential to develop targeted therapeutics in a similar manner as some of the new generation of cancer drugs.

Overall, though the field of DNA is still young, the research is advancing at a breakneck pace toward translational science that is making an impact on health care, electronics, and other applications.

While Chang and Yan agree that there is still much room to explore the manipulation and optimization of the nanotechnology, it also holds great promise. "With this proof of concept, the range of antigens that we could use for synthetic vaccine develop is really unlimited," said Chang.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by funding from the Department of Defense and National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Drug Abuse).

Scientists explore new class of synthetic vaccines

2012-07-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Force of habit: Stress hormones switch off areas of the brain for goal-directed behaviour

2012-07-26

Cognition psychologists at the Ruhr-Universität together with colleagues from the University Hospital Bergmannsheil (Prof. Dr. Martin Tegenthoff) have discovered why stressed persons are more likely to lapse back into habits than to behave goal-directed. The team of PD Dr. Lars Schwabe and Prof. Dr. Oliver Wolf from the Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience have mimicked a stress situation in the body using drugs. They then examined the brain activity using functional MRI scanning. The researchers have now reported in the Journal of Neuroscience that the interaction of the ...

Women have a poorer quality of life after a stroke or mini stroke than men

2012-07-26

Having a stroke or mini stroke has a much more profound effect on women than men when it comes to their quality of life, according to research published in the August issue of the Journal of Clinical Nursing.

Swedish researchers at Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, asked all patients attending an out-patient clinic over a 16-month period to complete the Nottingham Health Profile, a generic quality of life survey used to measure subjective physical, emotional and social aspects of health.

A total of 496 patients agreed to take part – 379 were stroke patients and 117 had ...

Research charts growing threats to biodiversity 'arks'

2012-07-26

Many of the world's tropical protected areas are struggling to sustain their biodiversity, according to a study by more than 200 scientists from around the world.

But the study published in Nature includes research focusing on a reserve in Tanzania by University of York scientists that indicates that long-term engagement with conservation has positive results

Dr Andy Marshall, of the Environment Department at York and Director of Conservation Science at Flamingo Land, compared the data he collected in the Udzungwa mountains with data collected more than 20 years previously ...

Aesop's Fable unlocks how we think

2012-07-26

Cambridge scientists have used an age-old fable to help illustrate how we think differently to other animals.

Lucy Cheke, a PhD student at the University of Cambridge's Department of Experimental Psychology expanded Aesop's fable into three tasks of varying complexity and compared the performance of Eurasian Jays with local school children.

The task that set the children apart from the Jays involved a mechanism which was counter-intuitive as it was hidden under an opaque surface. Neither the birds nor the children were able to learn how the mechanism worked, but the ...

Obama needs to show Americans he's still 'one of them'

2012-07-26

To win a second term in office, President Obama needs to persuade voters that he is still one of them – and recapture some of the charisma that help propel him to the top four years ago. However, this is clearly a challenge given the economic difficulties facing many Americans. Writing in Scientific American Mind, Professors Alex Haslam of the University of Exeter and Stephen Reicher of St Andrews describe how presenting themselves as 'one of us' is central to leaders being seen as a charismatic.

Rather than being an inherent personal quality, they identify charisma ...

With the crisis, less money is wagered but more people play

2012-07-26

This press release is available in Spanish.

VIDEO:

Researchers at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid have recently published a report which analyzes the impact of the economic crisis on gambling and the social perception of games of...

Click here for more information.

Scientists from the Institute of Policy and Governance (whose initials in Spanish are IPOLGOB) at the UC3M have ...

Cyberbullying: 1 in 2 victims suffer from the distribution of embarrassing photos and videos

2012-07-26

This press release is available in German.

Embarrassing personal photos and videos circulating in the Internet: researchers at Bielefeld University have discovered that young people who fall victim to cyberbullying or cyber harassment suffer most when fellow pupils make them objects of ridicule by distributing photographic material. According to an online survey published on Thursday 19 July, about half of the victims feel very stressed or severely stressed by this type of behaviour. 1,881 schoolchildren living in Germany took part in the survey conducted by the ...

Key function of protein discovered for obtaining blood stem cells as source for transplants

2012-07-26

Researchers from IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute) have deciphered the function executed by a protein called β-catenin in generating blood tissue stem cells. These cells, also called haematopoietic, are used as a source for transplants that form part of the therapies to fight different types of leukaemia. The results obtained will open the doors to produce these stem cells in the laboratory and, thus, improve the quality and quantity of these surgical procedures. This will let patients with no compatible donors be able to benefit from this discovery ...

2 Solar System puzzles solved

2012-07-26

Washington, D.C.— Comets and asteroids preserve the building blocks of our Solar System and should help explain its origin. But there are unsolved puzzles. For example, how did icy comets obtain particles that formed at high temperatures, and how did these refractory particles acquire rims with different compositions? Carnegie's theoretical astrophysicist Alan Boss and cosmochemist Conel Alexander* are the first to model the trajectories of such particles in the unstable disk of gas and dust that formed the Solar System. They found that these refractory particles could ...

Forest carbon monitoring breakthrough in Colombia

2012-07-26

Washington, D.C.—Using new, highly efficient techniques, Carnegie and Colombian scientists have developed accurate high-resolution maps of the carbon stocks locked in tropical vegetation for 40% of the Colombian Amazon (165,000 square kilometers/64,000 square miles), an area about four times the size of Switzerland. Until now, the inability to accurately quantify carbon stocks at high spatial resolution over large areas has hindered the United Nations' Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program, which is aimed at creating financial value ...