(Press-News.org) Scientists of the Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine have breathed new life into a forgotten technique and so succeeded in detecting resistant tuberculosis in circumstances where so far this was hardly feasible. Tuberculosis bacilli that have become resistant against our major antibiotics are a serious threat to world health.

If we do not take efficient and fast action, 'multiresistant tuberculosis' may become a worldwide epidemic, wiping out all medical achievements of the last decades.

A century ago tuberculosis was a lugubrious word, more terrifying than 'cancer' is today. And rightly so. Over the nineteenth and twentieth century it took a billion lives – more than the world population in 1800. Only in the nineteen fifties it became possible to push the disease back, with newly developed antibiotics. Countless sanatoria in Switzerland were closed one after the other and converted into hotels. Today almost nobody in the industrialized world still grasps the gruesome nature of 'consumption disease'. The treatment was so successful that the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1960 decided to eradicate tuberculosis once and for all. It almost worked.

But Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a tough adversary, demanding a treatment with several antibiotics simultaneously during months on end. Hardly feasible in developing countries. The numerous erratic or halted treatments led to growing numbers of bacilli that were resistant to several antibiotics. In the early eighties the death toll first stagnated and then got up again. The arrival of AIDS in the same period made things worse, because an infection with the one makes you more susceptible to the other.

Today we witness a growing number of 'multiresistant' tuberculosis, withstanding our best medicines, and only treatable with a costly and long cure of toxic drugs. Unfeasible in developing countries. According to WHO estimations, of the 5 million or so multiresistant cases of the last decade, only one percent had access to treatment. In 1991, a tuberculosis bug in New York was found to be resistant to 11 antibiotics. Cases have been reported where each and every antibiotic was useless. So far, these 'omniresistant' bacilli each time perished with their host before they could spread. So far, that is.

In 2012 on average 1 in 30 of new TB cases worldwide was multiresistant, with peaks of 1 in 3. With patients relapsing after a first cure, on average 1 in 5 was multiresistant, with peaks up to 65%. The highest numbers were all registered in the former Soviet Union. Without active measures the numbers will only rise.

If we want to prevent an epidemic of difficult to treat tuberculosis, then resistant cases, which do not react to the normal treatment, need to be recognized as early as possible, and immediately treated with second-line antibiotics that still work. But the laboratory tests to identify resistant TB bugs are cumbersome – the WHO estimates that in 2009 only 11% of multiresistant cases were discovered.

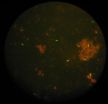

Checking smears under the microscope still is the recommended technique for TB screening, but it cannot differentiate between living and dead bacilli. So you do not know if you are looking at the cadavers of a successful treatment, or at resistant survivors. Only if the numbers after a long wait still don't fall, you know you are dealing with a resistant strain. But all that time the patient has remained contagious.

With high-tech PCR technology one can immediately ascertain if the bacillus is from a resistant strain, but in practice and certainly in resource-limited countries this is unfeasible. It also is impossible to cultivate every sample and then bombard it with every possible antibiotic to survey which ones still work for that individual patient.

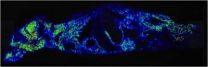

Armand Van Deun and colleagues therefore gave a new application to a forgotten technique: vital staining with fluorescein diacetate (FDA). It only stains living TB bacilli, so one immediately sees those bacilli escaping treatment. The scientists improved the detection of the luminous bacilli by replacing the classical fluorescence microscope with its LED counterpart. Together with colleagues in Bangladesh they tested the approach in the field for four years. This was made possible by a grant from the Damien Foundation – another possible sponsor had fobbed them off because their technique was too unknown.

But their approach works, also in a poor country. If after treatment the FDA-test was negative, in 95% of cases more elaborate tests didn't find active bacilli in the patient's sputum either. And if the test was positive, you could bet your boots that you had found a resistant bacillus.

This simple test allows, also in resource-limited labs, to detect a high number of resistant TB bacilli that otherwise would have been discovered too late or not at all. The scientists report in the International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease that three times more patients could directly switch to the correct second-line treatment without losing time on a regimen ineffective against their resistant bacilli. On top of that, the technique can cut in half the number of cases where doctors start a retreatment 'just to stay on the safe side', because it ascertains that the bacilli detected by the classical microscopy in fact are dead ones, which do not require further treatment.

INFORMATION:

New approach of resistant tuberculosis

2012-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How much nitrogen is fixed in the ocean?

2012-08-10

Of course scientists like it when the results of measurements fit with each other. However, when they carry out measurements in nature and compare their values, the results are rarely "smooth". A contemporary example is the ocean's nitrogen budget. Here, the question is: how much nitrogen is being fixed in the ocean and how much is released? "The answer to this question is important to predicting future climate development. All organisms need fixed nitrogen in order to build genetic material and biomass", explains Professor Julie LaRoche from the GEOMAR | Helmholtz Centre ...

Stem cells may prevent post-injury arthritis

2012-08-10

DURHAM, N.C.-- Duke researchers may have found a promising stem cell therapy for preventing osteoarthritis after a joint injury.

Injuring a joint greatly raises the odds of getting a form of osteoarthritis called post-traumatic arthritis, or PTA. There are no therapies yet that modify or slow the progression of arthritis after injury.

Researchers at Duke University Health System have found a very promising therapeutic approach to PTA using a type of stem cell, called mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), in mice with fractures that typically would lead to them developing ...

Autonomous robotic plane flies indoors

2012-08-10

CAMBRDIGE, Mass. — For decades, academic and industry researchers have been working on control algorithms for autonomous helicopters — robotic helicopters that pilot themselves, rather than requiring remote human guidance. Dozens of research teams have competed in a series of autonomous-helicopter challenges posed by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI); progress has been so rapid that the last two challenges have involved indoor navigation without the use of GPS.

But MIT's Robust Robotics Group — which fielded the team that won the last ...

Good news: Migraines hurt your head but not your brain

2012-08-10

Boston, MA—Migraines currently affect about 20 percent of the female population, and while these headaches are common, there are many unanswered questions surrounding this complex disease. Previous studies have linked this disorder to an increased risk of stroke and structural brain lesions, but it has remained unclear whether migraines had other negative consequences such as dementia or cognitive decline. According to new research from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), migraines are not associated with cognitive decline.

This study is published online by the British ...

New regulatory mechanism discovered in cell system for eliminating unneeded proteins

2012-08-10

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 10, 2012) A faulty gene linked to a rare blood vessel disorder has led investigators to discover a mechanism involved in determining the fate of possibly thousands of proteins working inside cells.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists directed the study, which provides insight into one of the body's most important regulatory systems, the ubiquitin system. Cells use it to get rid of unneeded proteins. Problems in this system have been tied to cancers, infections and other diseases. The work appears in today's print edition of the journal ...

Why do organisms build tissues they seemingly never use?

2012-08-10

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Why, after millions of years of evolution, do organisms build structures that seemingly serve no purpose?

A study conducted at Michigan State University and published in the current issue of The American Naturalist investigates the evolutionary reasons why organisms go through developmental stages that appear unnecessary.

"Many animals build tissues and structures they don't appear to use, and then they disappear," said Jeff Clune, lead author and former doctoral student at MSU's BEACON Center of Evolution in Action. "It's comparable to building ...

Individualized care best for lymphedema patients, MU researcher says

2012-08-10

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Millions of American cancer survivors experience chronic discomfort as a result of lymphedema, a common side effect of surgery and radiation therapy in which affected areas swell due to protein-rich fluid buildup. After reviewing published literature on lymphedema treatments, a University of Missouri researcher says emphasizing patients' quality of life rather than focusing solely on reducing swelling is critical to effectively managing the condition.

Jane Armer, professor in the MU Sinclair School of Nursing and director of nursing research at Ellis Fischel ...

Spending more on trauma care doesn't translate to higher survival rates

2012-08-10

A large-scale review of national patient records reveals that although survival rates are the same, the cost of treating trauma patients in the western United States is 33 percent higher than the bill for treating similarly injured patients in the Northeast. Overall, treatment costs were lower in the Northeast than anywhere in the United States.

The findings by Johns Hopkins researchers, published in The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, suggest that skyrocketing health care costs could be reined in if analysts focus on how caregivers in lower-cost regions manage ...

Stabilizing shell effects in heaviest elements directly measured

2012-08-10

This press release is available in German.

So-called "superheavy" elements owe their very existence exclusively to shell effects within the atomic nucleus. Without this stabilization they would disintegrate in a split second due to the strong repulsion between their many protons. The constituents of an atomic nucleus, the protons and neutrons, organize themselves in shells. Certain "magic" configurations with completely filled shells render the protons and neutrons to be more strongly bound together.

Long-standing theoretical predictions suggest that also in superheavy ...

Team creates new view of body's infection response

2012-08-10

A new 3-D view of the body's response to infection – and the ability to identify proteins involved in the response – could point to novel biomarkers and therapeutic agents for infectious diseases.

Vanderbilt University scientists in multiple disciplines combined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and imaging mass spectrometry to visualize the inflammatory response to a bacterial infection in mice. The techniques, described in Cell Host & Microbe and featured on the journal cover, offer opportunities for discovering proteins not previously implicated in the inflammatory response.

Access ...